I made my first real friend when I was 11 and she was 12. Marsha moved in on the block. Soon after, her mother saw my mother in the backyard and said she had a daughter about my age. My mother said, let her come for lunch. Marsha wrote me recently, “Loved your mom. I remember the first time we met and I had lunch at your house. We had grilled cheese w tomato.” That was 72 years ago.

We had an enriched childhood together. Her jokes cracked me up. We played pickup sticks for hours, practicing the small motor control that would enable us to paint and draw later. We started a “firm” that didn’t do anything, but whose mere name, Morgan and White, let us believe we were real artists and writers.

We argued about whether the modernist movie theater, the Midwood, was more beautiful than the baroque Loews Kings on Flatbush Avenue. We did puppet theater in her basement for neighborhood kids. We put out a newspaper of our doings called The Little Issue. Only my uncle Jack bought a copy; he paid 25 cents, probably to encourage writing, typing and doing layout. We started a novel that began “Doctor Boshkov pressed the tips of his well-manicured fingers together.” On the anniversary of the day we met, we had an outing to Manhattan.

Marsha visited me in college. She kept me from putting on a hoity-toity North Shore of Boston accent by laughing her head off the first time I tried it on. We shared the travails of dating. We did our first trip to Europe together, living on $5 a day, going our separate ways in museums as art lovers do and telling our finds at dinner.

After college we never lived in the same city again. She married. I went to various graduate schools, married and settled around Boston. In the child-raising years, we saw little of each other but kept up. When she divorced, her ex-husband kindly called to tell me she would like to hear from me. We picked up the friendship again. I have one of her paintings where I see it every day. When her second husband died, when she moved, we talked more often.

Nowadays, in our 80s, we email about our kids and grandkids, we discuss independent living and Continuing Care Retirement Communities. She’s as instinctually funny as she ever was. Her Facebook posts are either beautiful or a hoot. “Morgan and White” was a prologue to a working life: “Morgan” became a writer and “White” an artist—under our real names, of course.

I’m averse to nostalgia, I want to share my day to day and my opinions on the world’s current events. But it matters that I remember her parents, and she, mine. Marsha’s still one of my besties. She’s like my cousins—also childhood allies whose lives still crisscross with mine.

I’ve made newer friends, of course. But it’s delightful how many friends from college or graduate school are still lunchtime and Facetime and email pals. Andrea, in Andover, is a friend from college who became a bestie in our middle years, when both of us were starting second careers.

Some friends are distant in space. Connie is in LA, Penny is in Baltimore, Caroline in Maine. I’m in touch by email with one middle school friend, two high school friends. My women college classmates meet on Zoom once a month. We are more politically alike than we used to be; we are all feminists now.

Who said, “The last of life, for which the first was made”? It was Browning, of course, from “Rabbi Ben Ezra,” not a very good poem but worth it for this line. We never stop needing the old friends and relatives who have known us through many changes of our life course. Indeed, we cherish them more in later life, as some loved ones die and others move away.

My granddaughter, starting college, meeting many people, goes through the normal selection and elimination processes. She seems enchanted by the fact that I have kept so many close friends from those youthful years. Being accompanied as she grows up: it must seem miraculous.

My life course ahead, like everyone’s, is still unknown territory. I prize the companionship, while growing older. And it’s axiomatic that my friends and I have more in common now than we ever did. How could it be otherwise? Anecdote by anecdote, story by story, we add to the Memory Palace we share.

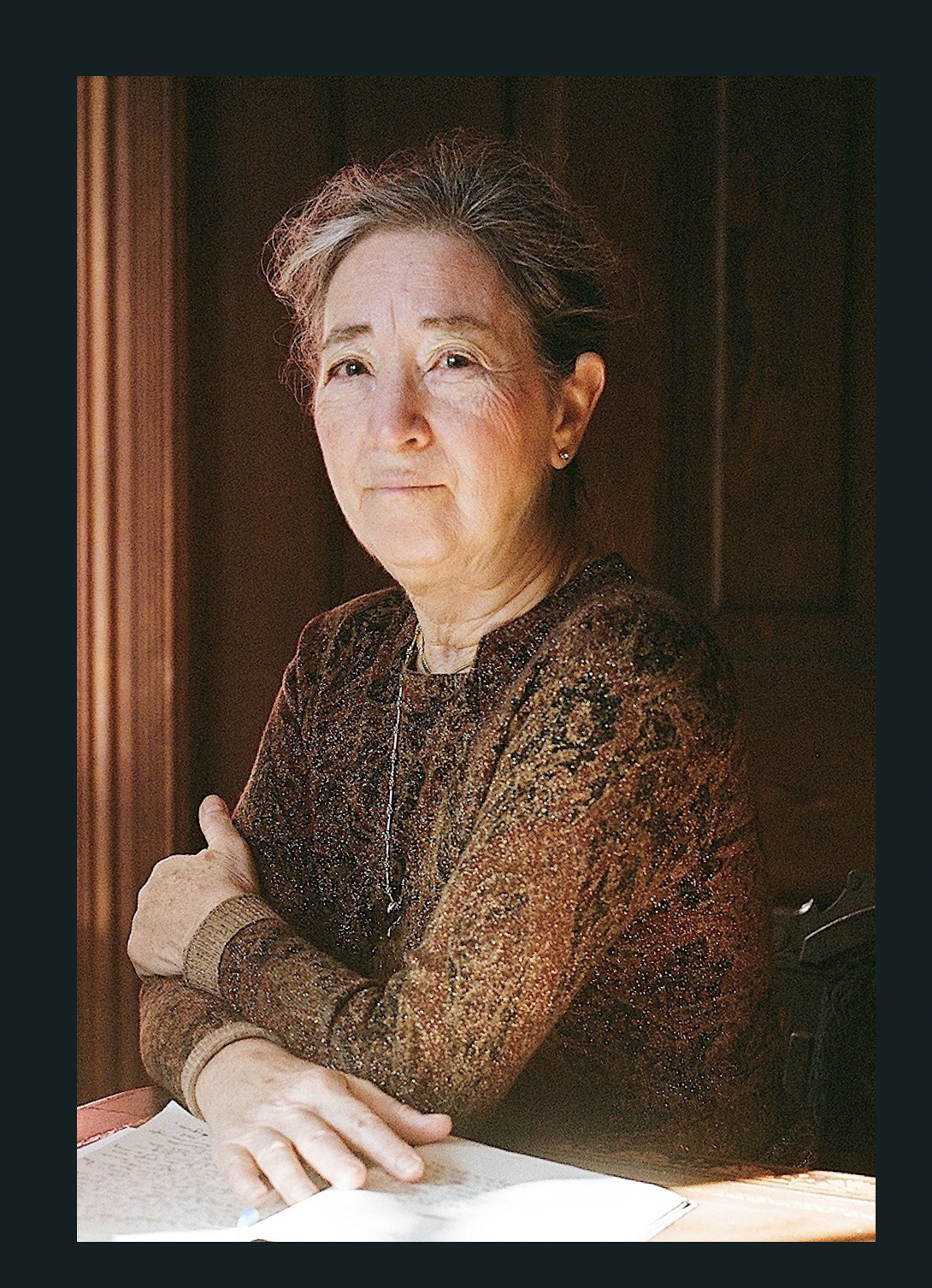

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.