My friend Jack called me a few weeks ago to share an experience.

He’d been at a public meeting at the library, seated at a table with three forward-facing chairs. He was sitting in the chair on the left, a woman was in the chair at the other end of the table, and the middle chair was empty. He nodded a friendly greeting to that woman and, shortly thereafter, he said hello to another woman as she sat down in the middle chair. He told me that he’d guessed she was about 85 years old.

After the presentations concluded, there was time for small-group discussions at each table. The woman next to Jack went out to the bathroom, and he started talking with the other woman at the table, who countered, “Let’s wait until your wife gets back from the bathroom.”

On the phone, Jack laughed sheepishly. He admitted to being shocked that the woman could even think he was married to their table mate. He confided that his first thought was, “Do I really look that old?” At the time, he felt embarrassed. When he got home, he discussed it with his wife. He wasn’t proud of his reaction.

On the phone with me, he was again embarrassed—but not ashamed. He had realized his unconscious ageist bias quickly. I was glad he’d called me, but the story isn’t over. A week or so later, we had lunch together, and we revisited our phone call. We talked about judging other people based on assumptions, the nature of relationships and how one person’s appearance can reflect something about the other person. And during that lunch conversation, Jack realized something. It was an “aha” moment for him.

In our phone conversation, he told me that when he first saw the woman sitting down next to him, he’d thought she was about 85. But as he retold the story at lunch, Jack realized that he had not consciously thought about her age until she’d been referred to as his wife. In other words, his first impression of her age had been totally unconscious. Jack’s ageist assumptions about and judgments of the woman sitting next to him were totally unconscious until their “relationship” was mentioned, until he felt personally insulted. Jack was amazed by this realization.

This is a clear and fascinating example of how deep and common our unconscious biases can be. Because of a variety of reasons, including socialization, cognitive development, cultural influences, fear and stereotyping, we learn at early ages to “other” other people. We do it without thinking and even without realizing it. And the effects of this “othering” differ, given one’s power and privilege and resources.

For many white males in our mainstream culture, ageism can be the first glimpse into the othering phenomenon, a crack in the doorway of awareness. Jack and I both learned from his aha moment.

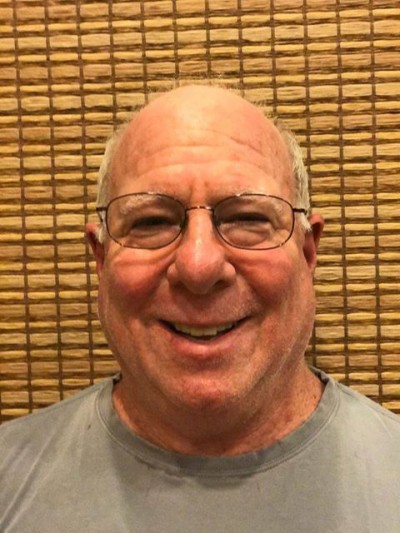

Marc Blesoff was a criminal defense attorney for 35 years, then he began facilitating Conscious Aging workshops, which has helped him melt the armor he’d built up as a defense lawyer. He’s a founding member of Courageus (formerly A Tribe Called Aging), a group of activists and thinkers trying to re-frame our culture’s outlook, policies and fears about aging and dying. Currently, he is the chairperson of the Oak Park, IL Aging-In-Place Commission.