I was sitting in my college dorm room, looking out the window as fluffy snow slowly fell from the sky. Snow in Baltimore was a pleasant surprise, a well-needed respite from my busy sophomore-year course load. I was interrupted when my phone vibrated in my pocket.

My friend Gertrude was calling.

It turned out, Gertrude was also watching snow fall. I told her I was happy to have one of my classes canceled. She told me she was annoyed that her plan for some retail therapy had to be postponed.

As we chatted, I almost forgot about the 60-year age difference between us. Gertrude was not like most of my friends, in that she was retired, had children and grandchildren and resided in an assisted-living community. Her apartment was way cleaner than my college dorm.

At the same time, she was similar to most of my friends: she loved the newest technology gadgets, hosted board-game nights with her friends and had a tenacious spirit. Gertrude once told me, after a hip procedure, that “a little bit of rehab won’t get me down” because she had already endured childbirth, and it couldn’t be that bad.

Gertrude and I met through a service-learning course I took at Loyola University Maryland. I would drive to her apartment weekly, and she would reminisce about her past. At the end of the semester, I was to apply concepts in social psychology to our conversations for a final project.

Researchers have confirmed the benefits of reminiscing for older adults: more enjoyment in life, more confidence, less depression and sharper thinking. The act of reminiscing has also informed an evidence-based psychotherapy intervention called reminiscence therapy. Gertrude’s face lit up when she was reminiscing. By retelling her stories, she revisited laughter, joy and accomplishment, while also sharing what she learned from hardship. She told me she always looked forward to our visits.

I have yet to see anyone write about the benefits of reminiscence for the person hearing the stories. That intergenerational contact with Gertrude taught me about resilience, history and womanhood, and it challenged some of my ageist biases.

The first day I met Gertrude, I was expecting a quiet, frail, lonely older woman, someone I might be able to help or fix by volunteering my time and company. Boy, was I wrong.

Gertrude gave me a tour of her apartment, including her laptop, smartphone, tablet and Kindle. I remember thinking, Wow, she has more gadgets than I do. I was even more surprised to hear that Gertrude’s preferred method of communication was through Facebook messaging.

Not only did Gertrude own a lot of technology, but she absolutely did not need my help to navigate it. And when she toured me around her dining hall, waving to all her friends as she passed them in the hallway, I learned that Gertrude was quite popular.

My ageist beliefs were being challenged—in real time.

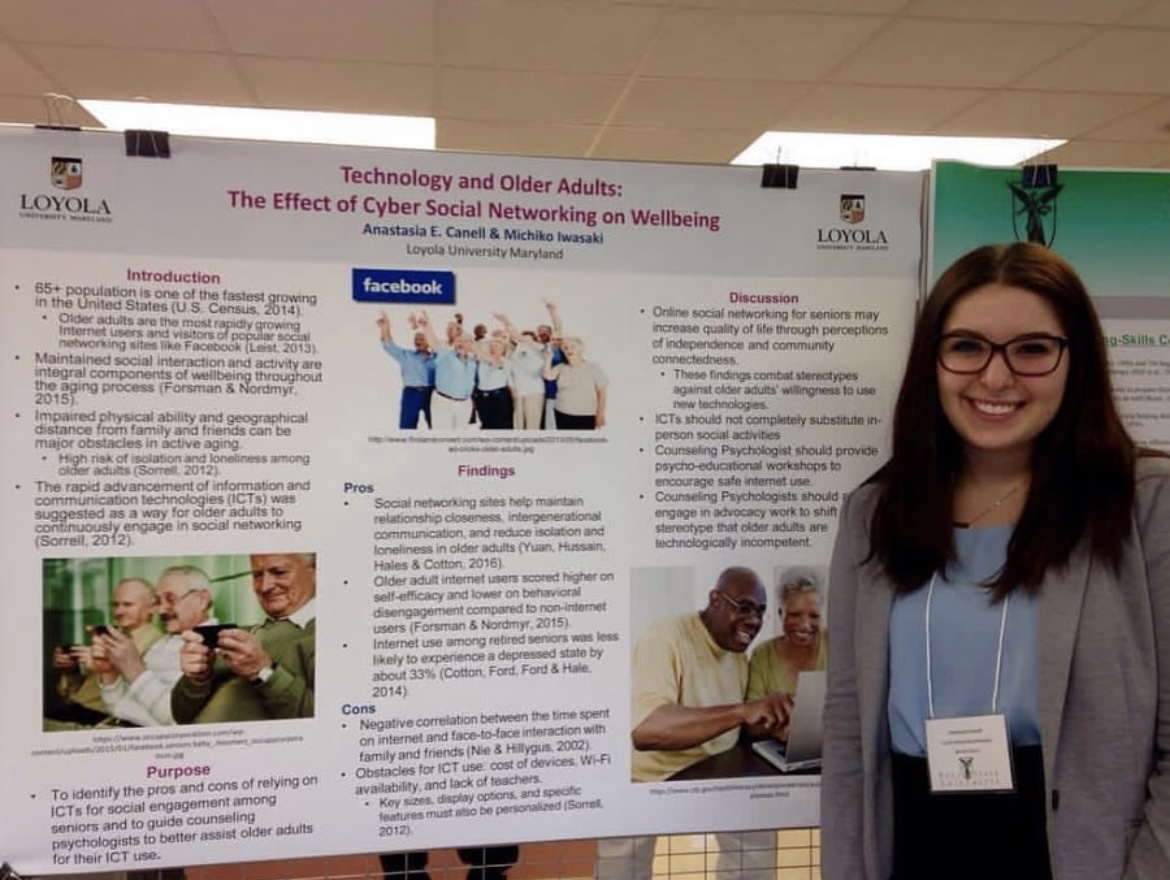

Meeting Gertrude made me wonder about older adults and technology use. Was she an anomaly? My curiosity brought me to a budding field of research. In 2016, I presented a synthesis of this research about social media use in older adult age groups at a regional psychology conference.

At the time, I learned that the fastest growing demographic on Facebook was users aged 65 and older, according to the Pew Research Center. This statistic is still accurate in 2024, and almost 50 percent of individuals over 65 are now on Facebook. Older adults are also becoming influencers on TikTok, creating dances there with their friends, sharing dating chronicles and giving fashion advice. I follow as many accounts as I can, to remind myself that older adults are the most diverse of all age groups, and to continue to challenge my ageist assumptions.

Gertrude and I remained friends after our service-learning formally ended. Through Facebook, of course.

Anastasia Canell has a PhD in clinical geropsychology, a specialty that focuses on understanding and helping older people and their families. As a postdoctoral fellow, she works in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities and elsewhere, providing psychotherapy for individuals and groups. She also does research and has written and spoken extensively about issues associated with aging, such as the way becoming an older person’s caregiver impacts young adults (18 to 25).