This hard-hitting essay was first published on March 15, 2023, in the Boston Globe. It’s re-posted here with the author’s permission.

This concerns all of us. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, many residents of nursing facilities died because they were crowded together in small rooms with other people, with often nothing more than a plastic shield between the beds. If an aide unknowingly carried the coronavirus into the cramped space and one resident caught the highly contagious disease, other roommates could too. They were all locked in, and their families and friends, social workers and the occasional ombudsman were locked out.

Most residents—despite being old and physically vulnerable—have survived the pandemic. They were resilient. But residents of the 363 nursing facilities in [Massachusetts] are still dying every week from COVID. They were individually special and well-loved, and their untimely deaths are deeply mourned.

The pandemic has driven home what a 2022 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine highlighted: the nation’s nursing home system is “ineffective, inefficient, inequitable, fragmented, and unsustainable.”

The best response to the sobering facts of danger and death would be to deinstitutionalize as many current, long term care residents as possible, returning them to their communities. That’s what most people yearn for. Expanding a government program called Money Follows the Person would make that possible for more long term care residents. The program also lowers costs. But because it is not possible to empty the nation’s 15,000 nursing homes of 1.2 million people, many of whom need care up to 24 hours a day, what then?

The answer is architectural, medical and ethical. Each person should get a private room if they want one—not a room with two beds or a single bed in a dormitory.

Being in their own room keeps vulnerable individuals safe. It makes residents feel more like human beings of value. Sweden and Denmark have moved to this higher standard.

In Massachusetts, the Department of Public Health mandated in 2021 that there be no more than two people to a nursing home room. That is better than before but still leaves the residents unhealthily confined. The space for a bed, a tiny chest of drawers or locker, a night table and a chair is allowed to be as small as 90 square feet. Two-person rooms provide no privacy. A roommate may snore, cry out in her sleep, drift into your space, watch TV 12 hours a day, take one of your few remaining precious possessions.

Only Dickens could do justice to this inhumane minimum. The federal government requires even less, only 80 square feet per person. A resident could be lying less than 6 feet of shared air away from the person in the next bed. Such regulations exist to prevent nursing facility owners from going even smaller.

Almost all the owners of the facilities in Massachusetts agreed without a fuss to the two-to-a-room mandate, even though they lose some Medicaid funding, which is allocated per head. The industry here now has many empty beds, partly from deaths, partly because potential clients are fleeing. Thirty-one owners refused to comply with the mandate and have sued the state to prevent it. Four, all in the western part of the state, are closing, rather than giving their residents more space.

When owners close facilities, the residents are often unable to find other accommodations. Often the available choices are badly run or farther from family. Good people in state government or nongovernmental organizations struggle to find them another placement.

There are two solutions. The state could build “small houses,” as it will be doing in a $400 million renovation of the infamous Holyoke Soldiers’ Home.

This approach, which is also known as the Green House model and admired in many states, cares for 10 to 12 people, each in a single room. One study, of three-quarters of the Green Houses and other small houses around the country, found that no one in that sample of centers died in that first terrifying spring and summer of 2020. In small houses, retention of aides improves. Residents’ health improves. Many emergency room visits are prevented; many illnesses are more safely treated in-house. Small houses offer the safety and dignity our elders deserve.

If we can achieve this for the veterans in Holyoke, why not for other vulnerable nursing home residents who need the same kind of skilled or constant care?

The second solution would be for the state to take over failing facilities. Many citizens dislike “lemon socialism”—when the government takes responsibility only for failing capitalist enterprises—but the situation of chaotic multiple closures and a wealthy pigheaded industry demands radical thinking.

Reformers have been begging for comprehensive improvements for decades. The state has some powers, but all over the country, the lobby is strong. Many nursing facilities are part of a multibillion-dollar industry and must provide high earnings for shareholders. A conscientious legislator, aiming to improve grim conditions, has at her ear an industry lobbyist whispering about helping her campaign—while he holds the threat of a home’s closure behind his back like a grenade.

Some of the two dozen bills before the Massachusetts Legislature aim to raise the minimums of care hours and improve working conditions. Giving residents more space without providing enough trained and well-paid aides would still be a guarantee of continuing misery, morbidity and mortality.

Under Governor Maura Healey, can the state finally be trusted to serve the elders in its charge with decency? By running refashioned facilities humanely and honestly and using guaranteed Medicare and Medicaid funds, the state could in one stroke save money and improve conditions.

We should all seek age and disability justice. Given a vast retirement savings crisis and increasing ill health, Gen X and Gen Z may also need a bed someday.

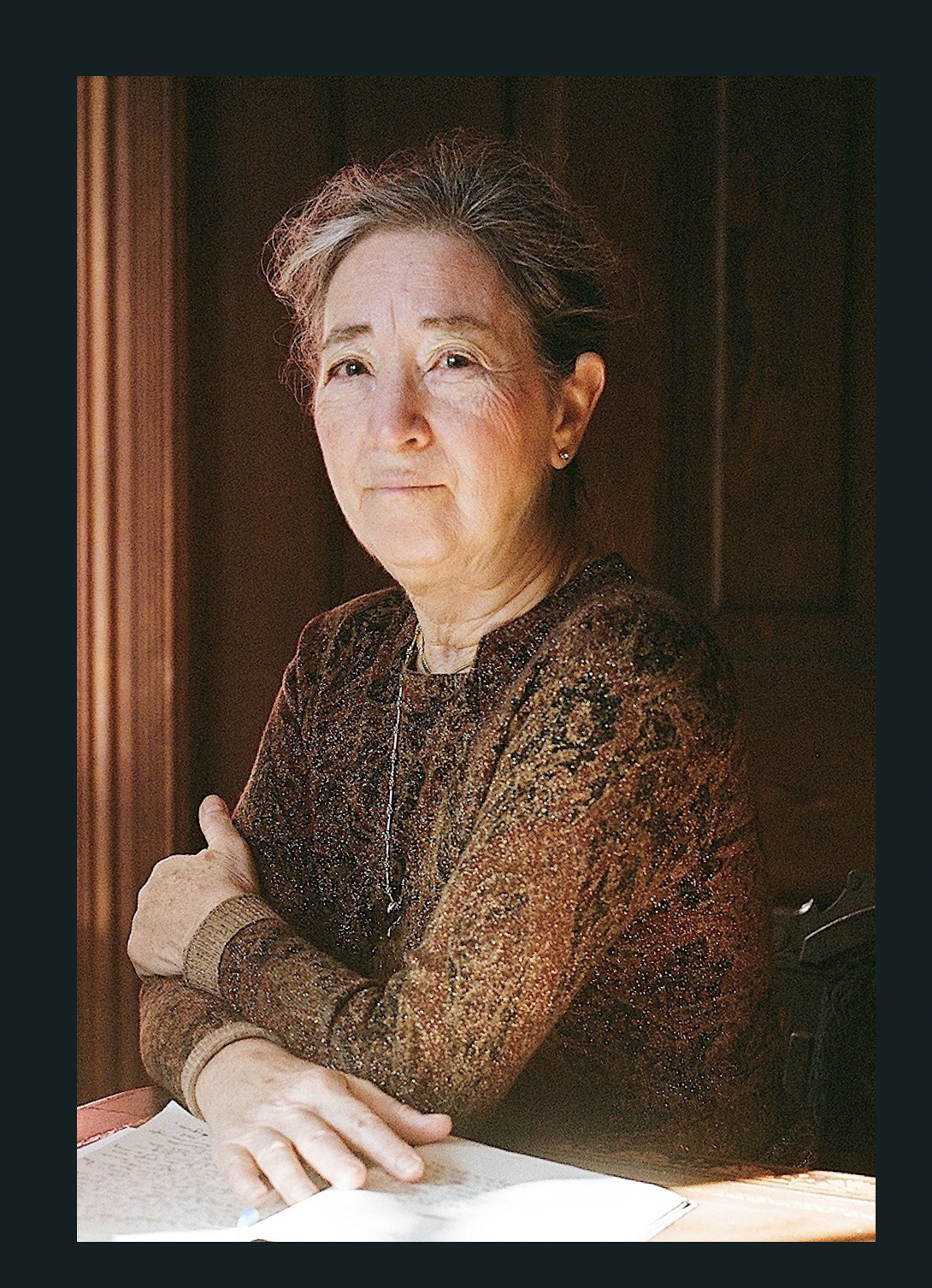

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.