Joy! Our first live theater event in almost two years, last week. With the booster and masked, my husband and I delightedly saw a one-woman show set in the 1960s, Queens Girl in the World, in which Jasmine Rush skillfully played all the voices, switching rapidly from12-year-old Jacqueline Marie Butler to Jackie’s West Indian father to Malcolm X and nine other characters. Good theater is life. We left, ecstatic.

Exhilaration! Our first dinner party inside the house, for my 80th birthday, occurred in May 2021. Four people who had received their first vaccination toasted, no masks. After an emotionally impoverished year, we gave one another long hugs. I had been storing them in my hug account, accruing interest. Summertime, our family came in for big withdrawals.

The future of increasing pleasure, liberty and love looks enchanting. This makes an amazing change from the tensions of March 2020. When we locked down, I had just returned from giving a keynote at a Milwaukee conference where people wanted to embrace the speaker. But the plane coming home was frighteningly empty; no one sat next to anyone else. I haven’t flown since. I won’t.

Waiting two scary weeks to see if I had acquired the virus, we took all recommended precautions. Our son, living with wife and daughters in the Brooklyn epicenter, suggested we get our groceries delivered, as he was doing. The young man next door received a fee for shopping for us until my husband went stir-crazy and insisted on doing errands, double-masked. Yes, we washed the plastic packaging. At the apartment of my 100-year-old aunt, who is perfectly healthy, her daughter put her mail aside for days. They don’t want me to visit yet.

Nowadays, my husband and I, triple vaxxed, are ready for every plausible normalcy. More liberty, more life, mehr licht [more light]. Travel? The next trip we are considering is to a high-ceilinged movie theater—“a Petri dish,” some call such venues—but with masks and social distancing, it promises delight.

Who Needs Precautions

Everyone I know—from 50 to 100—is comparing notes earnestly about their chosen degree of precaution, in order to live and live responsibly. This is not boring. Like weather in the Anthropocene [the epoch during which humans have had a significant impact on the planet], danger and pleasure have become critical matters in year two of the COVID Era.

For some parents and adult children, the level of precaution has become a fraught topic. A healthy couple—retired professionals, 90 and 92 and vaxxed—invite us for lunch. More warm hugs, no masks. A daughter nags them not to do this or that. Her father does a satirical impression of her tone. Clearly irked, he says dramatically, “98 percent of my life is behind me.” I take him to mean, “I want to choose what I do for the rest.” My position, as an age critic of four-score with a sideline in bioethics, is that adults are competent to make their own decisions about risk.

My aunt, a retired librarian, eager for variety, has two affectionately wary children but only herself to please.

The people who are rightly most cautious are those with threatening physical conditions. An acquaintance of 77, fighting cancer, awaiting radiation, visits with guests in his own living room—all wear N95s. A lovely neighbor who was about to marry wrote a note to all the wedding guests after her father had suddenly been hospitalized, explaining that “out of respect for everyone, you must be fully vaccinated and get tested if you have any symptoms …. [or] we will miss you!”

The new ethical protocol: whoever is most vulnerable decides the level of precautions. We others revel, cautiously.

It’s Not about Age

Navigating this moment has less to do with age than people typically think. Age alone is not a good predictor of death. It has been frailty and/or comorbidities that overwhelm the immune systems of COVID patients. Researchers first discovered this fact by studying hospitals in Italy, the first epicenter in the West.

In nursing homes in the United States, many people of healthy age survived. Sylvia Goldsholl, in a New Jersey facility, not only recovered from COVID, she had survived the deadly influenza of 1918-1919. Ms. Goldsholl said, of her family, “They knew that I was a wonder. …I met their expectations.” Among the 1.4 million people of diverse ages and physical and mental conditions residing in such facilities in 2019, hundreds of thousands of people, stereotyped as frail or ill, proved equally resilient.

But the facts about susceptibility to COVID were inadequately known. Some of the US triage-crisis guidelines actually suggested using age as the tie-breaker for ICU admissions, rather than likelihood of recovery, which is the preferred indicator. Under such an ageist guideline, one Donald Trump, 74 and obese, with a serious case of COVID, might not have been admitted. Instead, his body received bespoke care.

Those Who Make Me Nervous

The people I fear are strangers in the politicized worlds around us. At a Dunkin Donuts in southern Massachusetts, where one heavyset older man still vents about “Biden’s son making millions,” no one sitting around him wears a mask. When I tell the unmasked proprietor of a nearby market that everyone in Boston stores is masked, I can see with how stony a face he receives that information. Care for the vulnerable Other doesn’t always rule, Americans are ruefully learning.

Nor is age a good predictor of who will take basic precautions. Five conservative talk-show hosts—most in their sixties—having complained on air that the mortality figures were a hoax, subsequently died of COVID, as reported in the Boston Globe. Only one repented [before dying].

I understand, I share, the heady enchantments of normalcy. Still, an addiction to denying reality gives no one the right to act cavalierly about the lives of others.

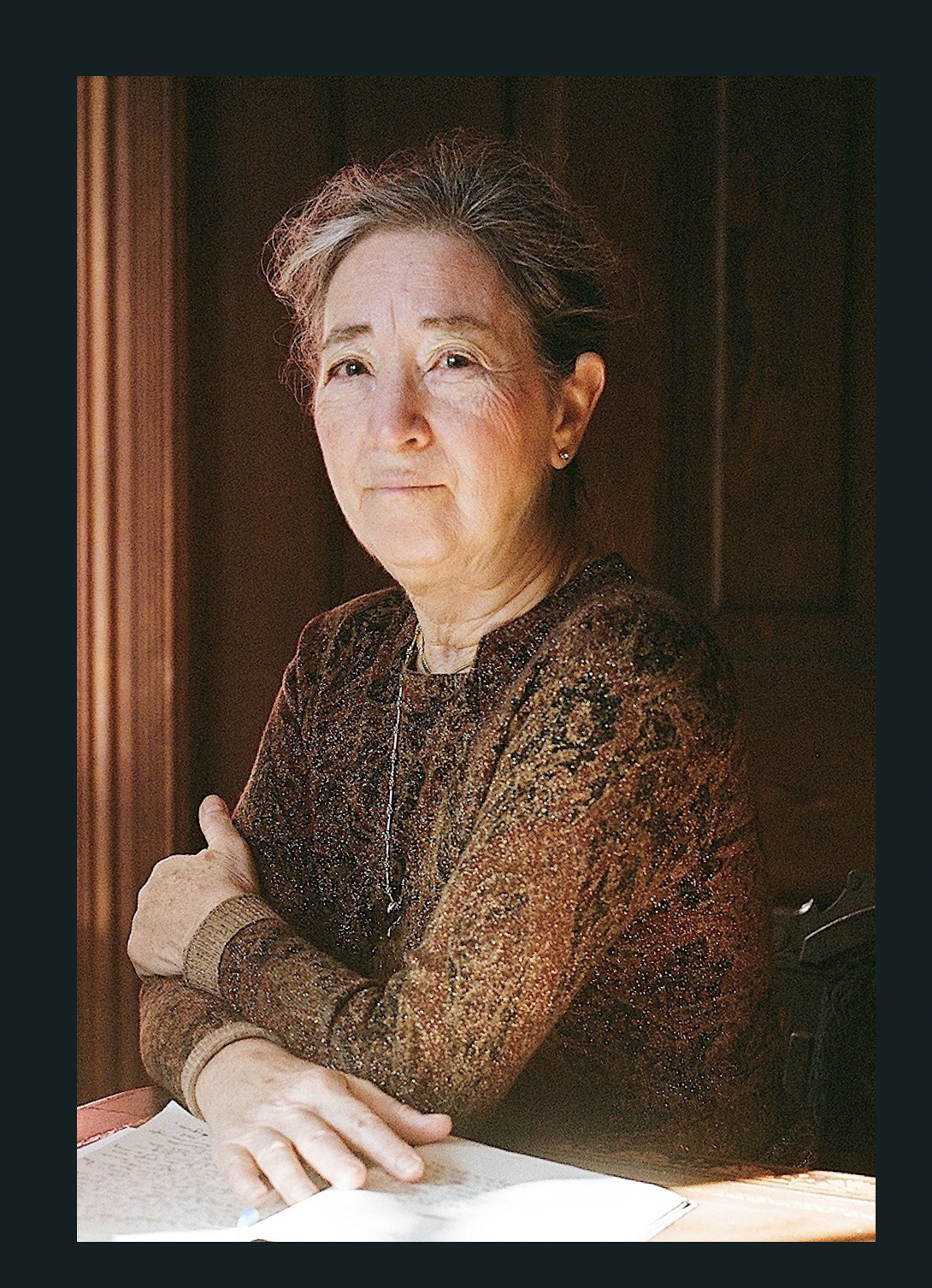

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.