A recent study analyzed data from all 50 states (plus DC) and found that, when it comes to ageism, New Jersey is the worst.

I was astounded when I read that. I’ve lived in New Jersey for most of my life, and it’s a liberal, open-minded place. Compared to the rest of the country, I would expect its citizens to be among the least likely to score high for any type of prejudice.

Not trusting the study, I did some digging—and learned something disturbing about myself in the process.

To begin with, after rereading reports on the study, I realized that the research wasn’t about explicit ageism. It focused instead on implicit ageism, and there’s a difference.

It’s explicit ageism when a corporate executive deliberately avoids hiring or promoting older workers, or when a doctor dismisses serious symptoms with a lofty “What do you expect at your age?”

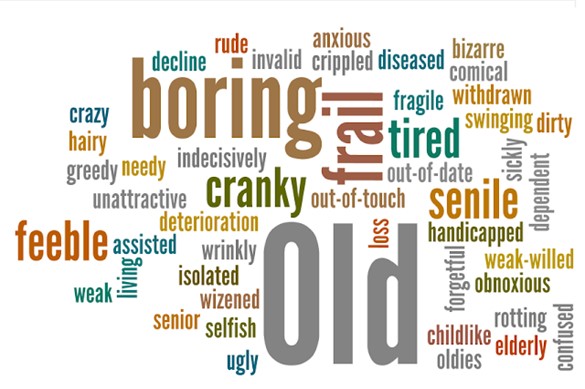

Implicit ageism, on the other hand, is subconscious. The term refers to attitudes and beliefs about old age, and stereotypes of older adults, that are buried so deeply we’re barely aware of them. But as a result, we dread our own later years and assume that older people are likely to be decrepit and confused.

People who would never deliberately say or do anything explicitly ageist can have implicit biases they’re not aware of.

The psychologists who conducted the 50-state study—Hannah L. Giasson, PhD, of Stanford University, and William J. Chopik, PhD, of Michigan State University—used an online test called the Implicit Association Test (IAT). Over 16 years, more than 800,000 people between 15 and 94 took a version of the IAT that measures age bias. Analyzing that data, the researchers found that New Jersey, Connecticut, South Carolina, North Carolina and Florida ranked high in implicit age bias, while Colorado, Montana and Utah had the lowest scores.

Then, since many studies have found that feeling negative about aging can have a negative effect on health, Giasson and Chopik checked health statistics. They learned that, in states with high rates of implicit ageism, a larger percentage of older adults were in poor health and the state spent more per capita on Medicare, compared to states with low rates.

That’s impressive, but I was still reluctant to believe that any kind of ageism runs rampant in New Jersey, so I took the IAT test myself. It’s available online—anyone can take it.

The test initially asks you to hit one key when you’re shown a photo of an old face and another key for a young face. (Telling the difference is easy.) After that, it records the speed with which you connect old and young faces with negative words such as “sick” or “selfish,” or positive words like “joyful” or “terrific.” People supposedly respond faster when faces and words (like an old face and the word “nasty”) are more closely related in their minds.

My score? I was told I’m moderately implicitly ageist (or words to that effect).

Who, me? I spend half my time reading and writing about ageism. Surely that couldn’t be true.

But according to the IAT website, I have lots of company: 77 percent of those who’ve been tested have been ageist to some degree.

This suggests that, thanks to our culture, we’re almost all ageist, whether we realize it or not—and it may help explain why older people often oppose the funding of programs intended to benefit their generation, such as Social Security, Medicare and even Meals on Wheels.

The IAT website assured me that a score like mine doesn’t mean I’m explicitly prejudiced against older adults. In fact, it said, IAT test results don’t indicate how any individual might behave. But when social scientists have considered test results en masse, if a lot of people in one group or one region are implicitly ageist, that does show up as discrimination in hiring and promotion or in medical treatment.

“When considering what it is like to grow old in the United States, where people live matters,” says Hannah Giasson, lead author of the 50-state study.

The researchers acknowledge, however, that many different features of a particular location can affect the quality of older people’s lives: access to affordable housing options, good health care, convenient public transportation, age-friendly public policies and so on.

The important thing about implicit ageism is how damaging it can be for those of us who harbor it. Having absorbed distressing ideas about what aging and older people were like, we turn those biases against ourselves in our later years. That’s bad for our health, undermines our self-confidence and can prevent us from getting the most out of our long lives.

Here’s just one, everyday example of what implicit ageism can do.

I live in a retirement community. Some years ago, our management asked residents whether we’d like to change the rules to allow people to wear shorts in our restaurants during the summer. The response was, “No way.”

As one resident put it, “I don’t want to have to look at old people’s legs. They’re ugly.”

Statements like that reflect implicit ageism. And I’m sure she judged her own body by the same standards.

I have to admit that I wouldn’t wear shorts to dinner or anywhere else. It’s a shame that, instead of appreciating a body that’s stayed resilient and healthy for 86 years now, I’m ashamed of the way it looks.

How do you shake off that kind of deeply buried prejudice against yourself? I don’t know, but I’m sure it helps to see it for what it is.

Flora Davis has written scores of magazine articles and is the author of five nonfiction books, including the award-winning Moving the Mountain: The Women’s Movement in America Since 1960 (1991, 1999). She currently lives in a retirement community and continues to work as a writer.