A few weeks ago, my granddaughter and I took a summertime walk to the local market. On the way home, the afternoon sun was at our backs. In front of me, I saw the shadow of an eight-year-old girl and her grandfather, holding hands as they walked.

I was momentarily surprised that it was me, and then I smiled appreciatively. What a beautiful sight—my own shadow as an older person. What a wonderful image, and it was me!

Seeing that flash of shadow reminded me of my present age as well as when I was an eight-year-old. I remembered spending time every summer at a lake near where I grew up. Our family still makes recurring pilgrimages to that lake.

Anytime I wanted, I’d run full steam down the hill, arms outstretched like wings, and just plunge into the water. Ducks, frogs, minnows, turtles and sunfish would make room for me. I loved the exhilaration of swimming underwater with my eyes open, surveying the lake bottom, and then bursting through the surface for a gulp of air and to feel the warmth of the sun.

My granddaughter and I have been looking forward to jumping into that lake when we make our post-vaccination pilgrimage this summer—perhaps jumping in as we are holding hands! That would be another wonderful shadow to see.

That changed with an email detailing how swimming has been banned in the lake because of cyanobacteria. What? No swimming? This lake is 15 miles around!

Cyanobacteria phytoplankton form the base of the food web of some freshwater ponds and streams. The presence of cyanobacteria is natural and important, but too much cyanobacterial growth (called blooms) leads to the release of dangerous amounts of cyanotoxins, which can poison wildlife, humans and pets. Over the past decade, there have been late-fall blooms of cyanobacteria in the lake, but never as early as mid-June and never enough to force people and pets out of the water.

Global warming, fertilizer runoff and septic tank seepage have combined to create blooms and to change the world I knew. That world would have changed no matter what. Life is change. But this is harmful, human-made change, which is not inevitable.

As we age, we have a continuing responsibility to be good stewards, good role models, and to work alongside younger people to right the wrongs. One aspect of aging with intention is to share and listen while forging intergenerational relationships.

Not everyone grows up near a lake, but all of us older people will have our own cyanobacteria in one form or another—systemic harm that hits close to home. It could be ecological security or economic security or health security or job security. It could be the intersection of ageism with ableism or racism or sexism or homophobia.

Toxic cyanobacteria blooms are one thing calling me to activism in my third stage of life. What calls to you to age with intention?

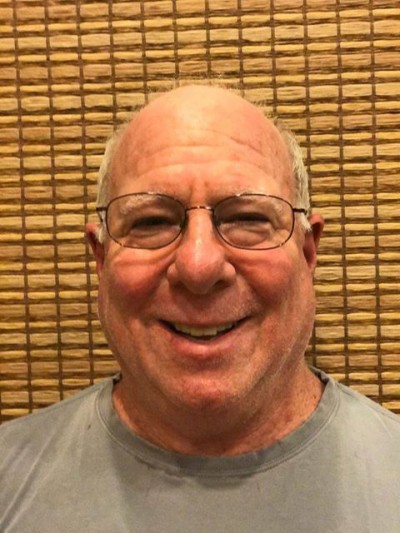

Marc Blesoff was a criminal defense attorney for 35 years, then he began facilitating Conscious Aging workshops, which has helped him melt the armor he’d built up as a defense lawyer. He’s a founding member of Courageus (formerly A Tribe Called Aging), a group of activists and thinkers trying to re-frame our culture’s outlook, policies and fears about aging and dying. Currently, he is the chairperson of the Oak Park, IL Aging-In-Place Commission.