I’m watching out my kitchen window as cars come and go from my neighbor Tony’s house. Last month, Tony celebrated his 89th birthday, and family came out of the woodwork. Last week, he left the hospital to die at home on hospice care; the family has returned. Saturday morning, I brought over some bagels, looking for information. Tony’s kids were grown and out of the house when I moved here 15 years ago, but I see the local ones regularly. In truth, I see the adult daughters. I asked one of the daughters how it was going with hospice. Her reply: don’t die on the weekend.

Like many who are terminally ill, Tony insisted that he not die in a sterile and impersonal hospital, hooked up to machines. Despite the family’s lack of familiarity with dementia care, they brought him home. They weren’t told that hospice services would begin on Monday; they were on their own for the weekend with a man who would not go gently into that good night.

Tony’s daughters spent the better part of Friday night on the phone with the hospice helpline, learning which medications would help calm their frightened, agitated father. They needed to go to several pharmacies to fill the prescriptions and retrieve the items on the list from hospice. Sadly, Tony needed to be restrained until the medications kicked in. So much for the dignity they hoped would be a benefit to dying at home.

When a hospice nurse finally arrived, she only took his vitals and made a few suggestions for the family to keep Tony comfortable. Tony was polite to her, but he had been horrible to his family. The nurse had no resolution for that.

My own experience with my mother’s end-of-life wishes and her hospice care was also disappointing. I had heard stories of the angels of hospice, so my expectations were high. I was also under the impression that the medical pieces would be handled by professionals. This was not the case.

I might have made a different choice for her if I had known the deeply intimate and personal care required of me and my sisters. The physical strength, fortitude and patience needed, even with a compliant patient like my mother, can’t be glossed over. Being a primary caregiver at the end of a loved one’s life requires resources beyond measure at a time when it’s hard to summon them. I regret that the caregiving took over the actual caring, but the tasks before me were overwhelming.

I don’t know if my neighbor has weeks or days, but I know it’s hard on the family. I now question if I can have a “good death” and die at home.

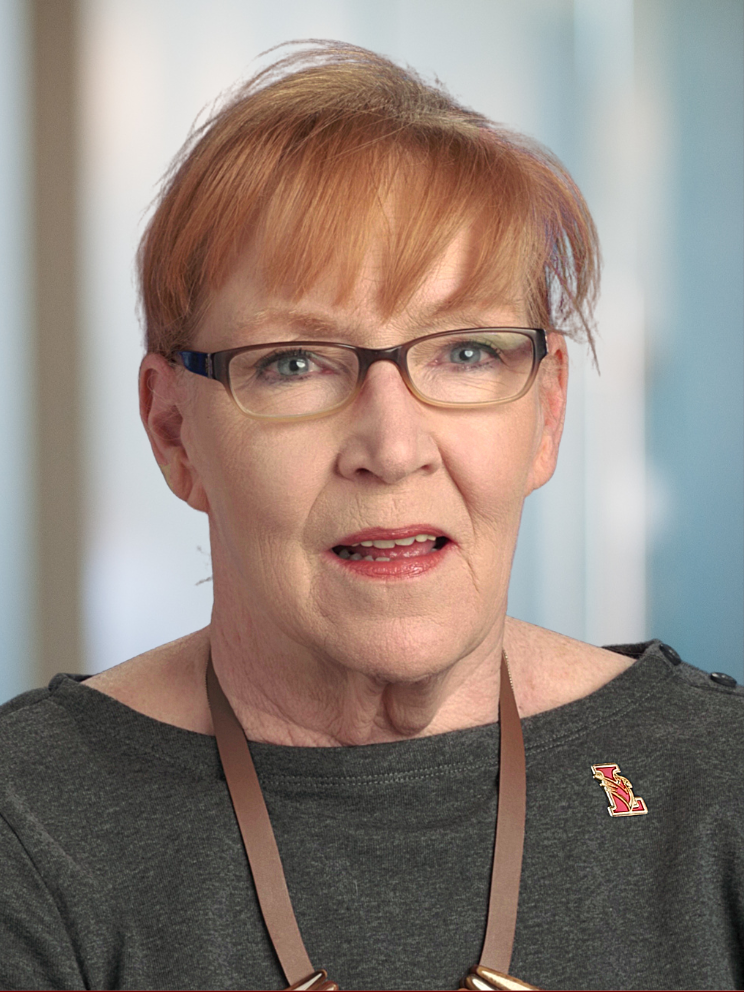

Pepper Evans works as an independent-living consultant, helping older adults age in place. She is the empty-nest mother of two adult daughters and has extensive personal and professional experience as a caregiver. She has worked as a researcher and editor for authors and filmmakers. She also puts her time and resources to use in the nonprofit sector and serves on the Board of Education in Lawrence Township, NJ.