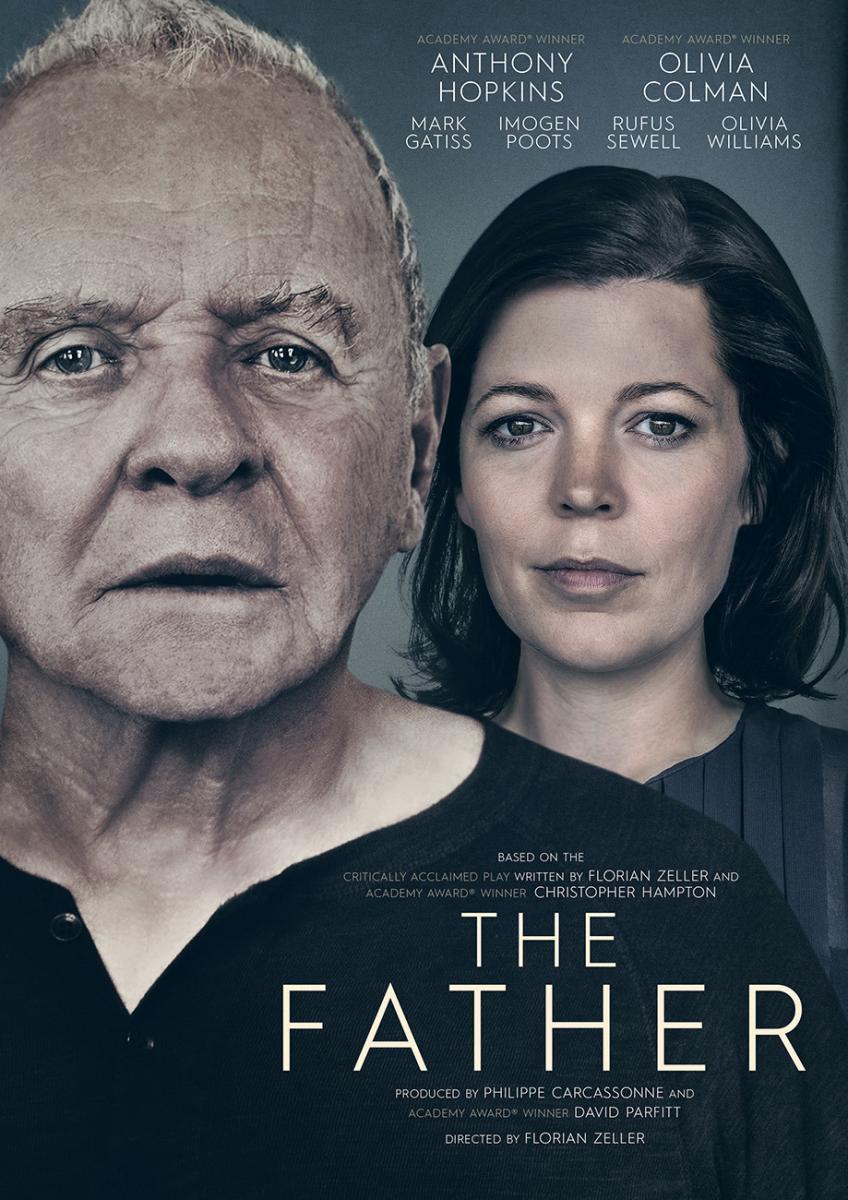

The Father has received much attention and won two (in my opinion well-deserved) Academy Awards. It engages viewers as no other movie about dementia has because they experience the effects of the disease the way the person living with it does—a stunning artistic achievement by writer-director Florian Zeller and actors Anthony Hopkins and Olivia Colman.

The film has moments of humor and moments in which we admire Anthony, the father (played by Anthony Hopkins), for his determination to hold onto his independence. But overall, there’s no denying it is a heartbreaking movie.

Before you decide to see it, ask yourself if you want to see what it’s like to live with dementia. If fear dominates your view of Alzheimer’s, that may prevent you from reaping the rewards of this film.

But if you are truly interested in how the world looks and feels to people living with dementia and want to better understand them, this movie presents a unique opportunity. It broke my heart, but I’m grateful for the deeper insight it gave me into someone trying to cope with cognitive loss.

The Father opens with a familiar struggle between the person with the disease and his carer. Anthony lives in his own apartment in London. His daughter, Anne, feels he needs the help of a full-time aide, but he disagrees and keeps firing those she hires. She is under pressure to get him set up securely because she is planning to move to France. After being single for five years following a divorce, Anne has fallen in love with a man who lives in Paris.

This sets the baseline for the story—or so we assume.

But as scene two unfolds, everything in that baseline is thrown into doubt. We are no longer sure whose apartment Anthony is in after he finds a strange man sitting in the living room who claims it is his flat. He also claims to be Anne’s husband, so we are no longer certain if she is married or divorced.

Understandably Anthony is confused by all this, so the husband decides to call Anne and summon her home from shopping.

Soon we hear the door open.

“It’s me!”

Anthony: “Ah. There she is.”

But when he sees her, Anthony looks frightened and bewildered.

“Is something wrong?” she asks.

“What is this nonsense?” he says.

“What are you talking about?”

“Where’s Anne?” Anthony demands.

“Sorry?”

“Anne!”

“I’m here. I just went to do some shopping, and now I’m back.”

This scene could be from any film about dementia. It’s the uh-oh-now-he-doesn’t-recognize-his-own-daughter moment from many a caregiver’s story. And in another film what we would feel is the loss this represents for the family member.

But this time we feel something quite different because we are inside Anthony’s mind. We experience it the same way he does. Director Zeller accomplishes this by showing us exactly what Anthony sees and allowing us to know only what Anthony knows.

When Anne enters, it’s not only her father who doesn’t recognize her; neither do we. This isn’t the Anne we met in scene one! We immediately suspect that something nefarious is going on.

Anthony speaks for us too when he says, “There’s something funny going on here, believe me!”

This film’s power comes from positioning the viewer so as to live the experience of the person with dementia, not just watch it. There is no way we can distance ourselves emotionally.

This is exactly Zeller’s intent: to have us feel what it is like to be losing our bearings.

To achieve this, he confuses us about some of the things that someone with cognitive impairment finds hard to keep track of: time, place and person.

To let us feel Anthony’s vanishing sense of time, Zeller scrambles it. Are we in Anne’s post-divorce time or when she is still married? It’s hard to tell because for a good part of the movie, her husband is present as her husband. Events suggest that these may be bad memories that Anthony can’t stop from seeping into the present. Some scenes repeat in altered form. One scene even circles around and ends where it started.

Zeller disorients us to place by continually making small changes in the apartment where Anthony lives. A piano disappears and is replaced by a sideboard. Walls change color. Kitchen cabinets and backsplashes change. All this is done so subtly we barely notice, but it is enough to unsettle us.

Not at all subtle is Zeller’s way of confusing us about person. By casting a different actor as Anne in the second scene, he makes us feel how unnerving and frightening it is to be told that the stranger in front of you is your daughter or wife.

Frightening. In 28 years of talking about this very issue with caregivers in the support groups I lead, no one, not even I, has mentioned that fear. We didn’t detect it because our focus was elsewhere. On the caregiver’s hurt and loss.

I was as sure as Anthony was that the woman wasn’t Anne, and to hear her insisting that she was scared me. It felt as though the movie had taken a terrible turn.

So effective is Zeller at making us share Anthony’s perspective, we hear things others say to him in a new way. Things we ourselves may have at least thought, if not said.

Anne’s husband says to Anthony in exasperation, “Sometimes I wonder if you are doing it deliberately.” By this time, Anthony’s bewilderment has become our own, and the statement feels cruel.

Anne is a kind and loving daughter but under pressure makes the same mistakes we all do. We see with shame how dismissive we can be of the concerns of the person with dementia because we don’t give them due weight.

Here’s an exchange between Anthony and Anne. They are at breakfast and awaiting the arrival of an aide he had decided he liked. Anthony is in his pajamas. The doorbell rings and Anthony panics because he is not yet dressed.

Anne: “You can get dressed later.”

Anthony: “No. No. I must get dressed!”

Anne replies, “It doesn’t matter.”

Anthony, desperately: “It does matter!”

Anne: “She’s outside the door!”

Anthony: “Please don’t leave me alone. What will she think of me? I’ve got to be properly dressed.”

Anne continues to dismiss his concern as she goes down the hall to answer the door.

This amounts to emotional abandonment.

It won’t come as a surprise to caregivers that Anthony can dole out plenty of cruelty himself. He fights to maintain control. With judgment and inhibition failing, he lashes out at Anne and derogates her to others. The hurt registers immediately on Olivia Colman’s marvelously expressive face.

This intimate step into a life with dementia is heartbreaking. But if you let it break your heart open to compassion, you’ll find it’s also surprisingly uplifting. Your awakened compassion will show you the deep humanity—and the need for love—that dementia can’t erase.

The Father is showing in theaters as pandemic restrictions ease, or you can rent it on streaming platforms such as Amazon Prime Video, Apple, Fandango, Google, YouTube and Vudu. Seeing it more than once is possible with streaming and can help you sort out some of the contradictions.

Maggie Sullivan has come to know Alzheimer’s intimately. She was caregiver and advocate during the eight years her mother lived with the disease. For the past 30 years, she has facilitated caregiver support groups for the Alzheimer’s Association, learning from the experience of more than 300 members of those groups. The opinions she expresses here are her own. Maggie is also a writer whose essays and articles have appeared in the New York Times and elsewhere.