This essay was first published on December 22, 2020, in American Prospect.

The 2020 presidential election took place at arguably the most anxious time in the nation’s history, at least as threatening as the Civil War, the flu epidemic of 1918–1919, or the distant world wars. Triple crises have been visited on us here at home: depression-like levels of unemployment with lethal inequality; white-on-Black violence more public and shameful than anything in recent history; and most of all, the catastrophic coronavirus epidemic with its incessant, remorseless reports of deaths, especially [of] our parents and grandparents, our mentors and guides—the generations that stand between younger people and mortality. These are trauma-inducing circumstances.

In these circumstances, I argue (for the sake of opening up new conversations) that this frightened nation needed a parental figure. Although much was made of the ages of the candidates, the ageism of that trope vanished as the psychic need rose, higher and more desperate, for certain magical, positive qualities associated with later life.

It’s not an older figure that people wanted so much. Their overriding psychic need was for an authority figure who could reassure. A parent, to be sure, but what kind of parent?

Perhaps a mother figure would have served even better as mentor and guide. In wartime, wounded men cry out for their mothers. But after Elizabeth Warren placed fifth in the South Carolina primary on February 29, she soon folded her campaign—just as the panic over COVID was starting. The following day, the World Health Organization announced a global pandemic.

Bernie Sanders would have been the psychic preference of many: the kind of reliable and knowledgeable father who says the same thing for decades and is vindicated. The propositions he repeats with emphatic, credible certainty, unlike those of the White House shouter, promise restoration. But he withdrew on April 8.

That left, on one side, the Bully Dad—the big table-banger who shouts everyone down—that too many men and women know from their battered childhoods. This figure can be racist, misogynistic, nationalistic, a sociopath, disinhibited; and at home he may have dominated and abused them and their mother. He may have narcissistically defeated their possibilities, for fear they would surpass him. He may have disciplined them for suffering rather than empathizing with their weaknesses.

This is the feared male figure whom some people have internalized as a winner. They call that swaggering walk, blustering talk, those threats and blatant lies “confidence.” With good reason, they may wish to annihilate him, but, that being out of the question, they try to emulate him. Adam Phillips, the British psychoanalyst, describes the aftermath of a toxic childhood, when “the adult impersonator, the child dressed as an adult, performs a precocious cartoon of what they have been subjected to.” The savage power relations of childhood, writ large, become their sadistic, divisive party politics.

The alternative was Joe Biden. Biden’s policy deficits, to left and right, melted away before his consistent self-presentation. Biden wasn’t my first choice, or my second, and at my age I don’t need a father figure. But in the existentially frightening COVID era, I can see the appeal of the mothering-father narrative: the senator who put his sons first every night after they lost their mother and sister.

The “Biden as senile” meme definitively stopped working after the first debate, when it was the toxic father who looked twitchily out of control. After that, Biden erased the stereotype, which gerontologists have noted for years, that older people who are considered “nice” are diminished by being considered “incompetent.” The attempt to taint him with other ageist stereotypes—garrulous—failed, not only because he became cogent and forceful when he broke through Trump’s noise, not only because of his long record of public service, but because his niceness connected to some deep, interior needs.

Biden’s town hall and the second debate cemented all his Good Father qualities. Personally, not that it matters, I warmed to him first when his granddaughters, squeezed onto a couch in a convention video, announced that he called them every day. Every day! And one said, giggling, they didn’t always pick up.

A New York psychoanalyst told me, of Kamala Harris, “She has a rescue quality.” She meant that Harris reads as loving. This attitude appeared even in Harris’s debate with VP Mike Pence. Pence’s stoniness did not diminish the smile she turned on him, that wise, skeptical look of a mother or a teacher who has seen all the shenanigans and sees through them to something better beneath—whether present or not. Acceptance is a form of kindness, a promise of reform. Hers made a good amalgam with Biden’s ability to represent goodwill to all.

There are facial expressions and gestures that can’t be faked. His earnest signature phrase, “Here’s the deal,” came with his most natural embrace of those who needed it, including some who feel all they deserve and know is a bullying, lying, but promise-making Dad. You could see the power of the steady embrace in Biden’s first speech as president-elect. He faced us in the audience with his hands out in front of him, as if framing our faces before him, having just listened intently to us all. This is his typical “holding” gesture. Therapists use the term “holding” as a metaphor for their ability to attend to troubled people. Biden has made the metaphor visual—has made it his. The Good Father is the one who plays no favorites among his children.

People can debate for years, and will, why Biden won, and give due credit to conscious choices: passionate levels of civic engagement, organizing new voters, the Democratic money advantage, hatred of Trump, the economic debacle, detestation of Republicans’ tax cuts for the rich, and recklessness about pandemic preventions for them. But Biden ran ahead of the average of other Democratic House candidates—so something read as good and generous inhered in him personally. In the reckonings, no one should omit the deep, psychic needs of the COVID era.

May they never be reproduced. May the United States never again have so many overwhelming causes to become a nation of terrified children.

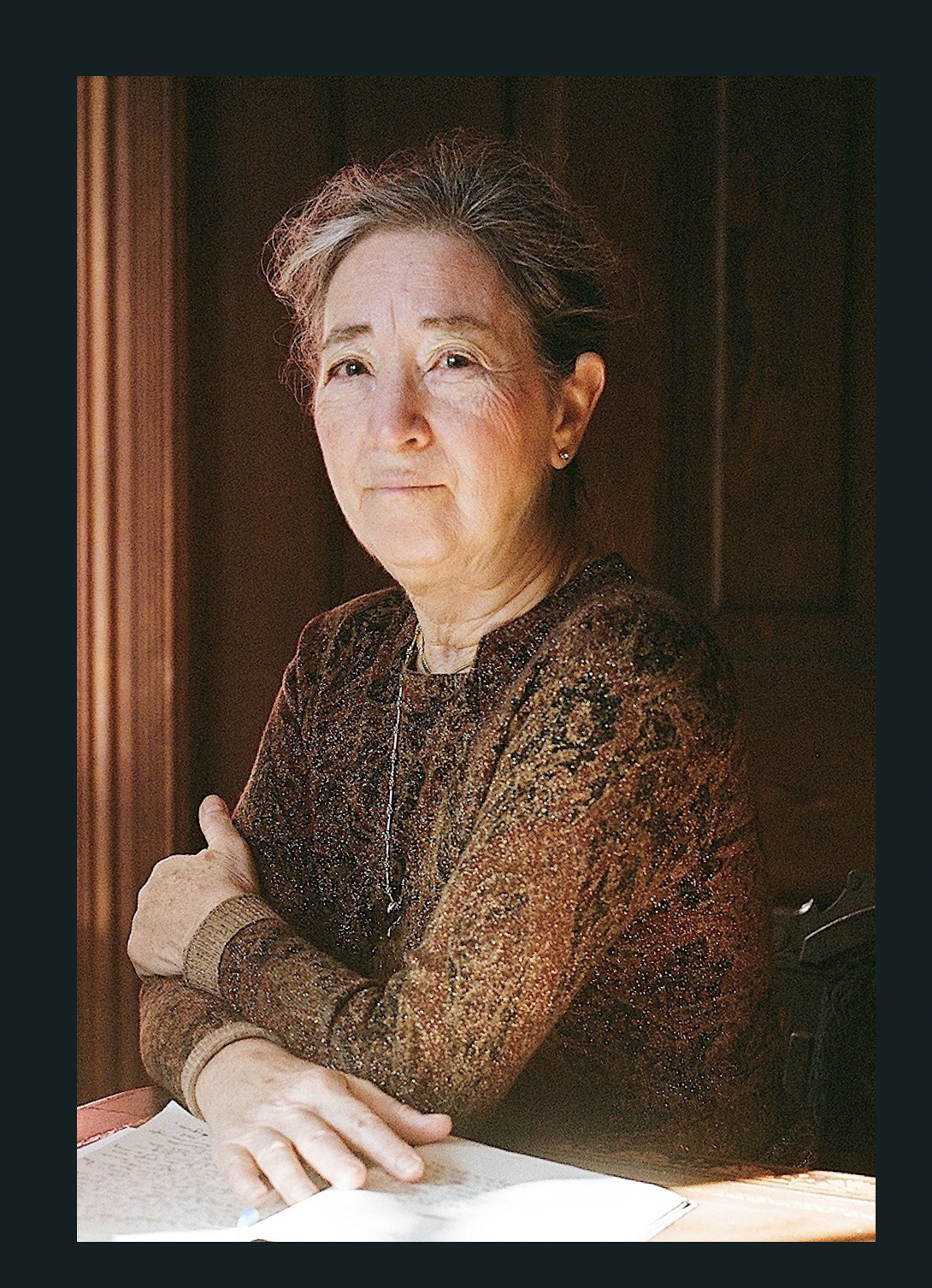

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.