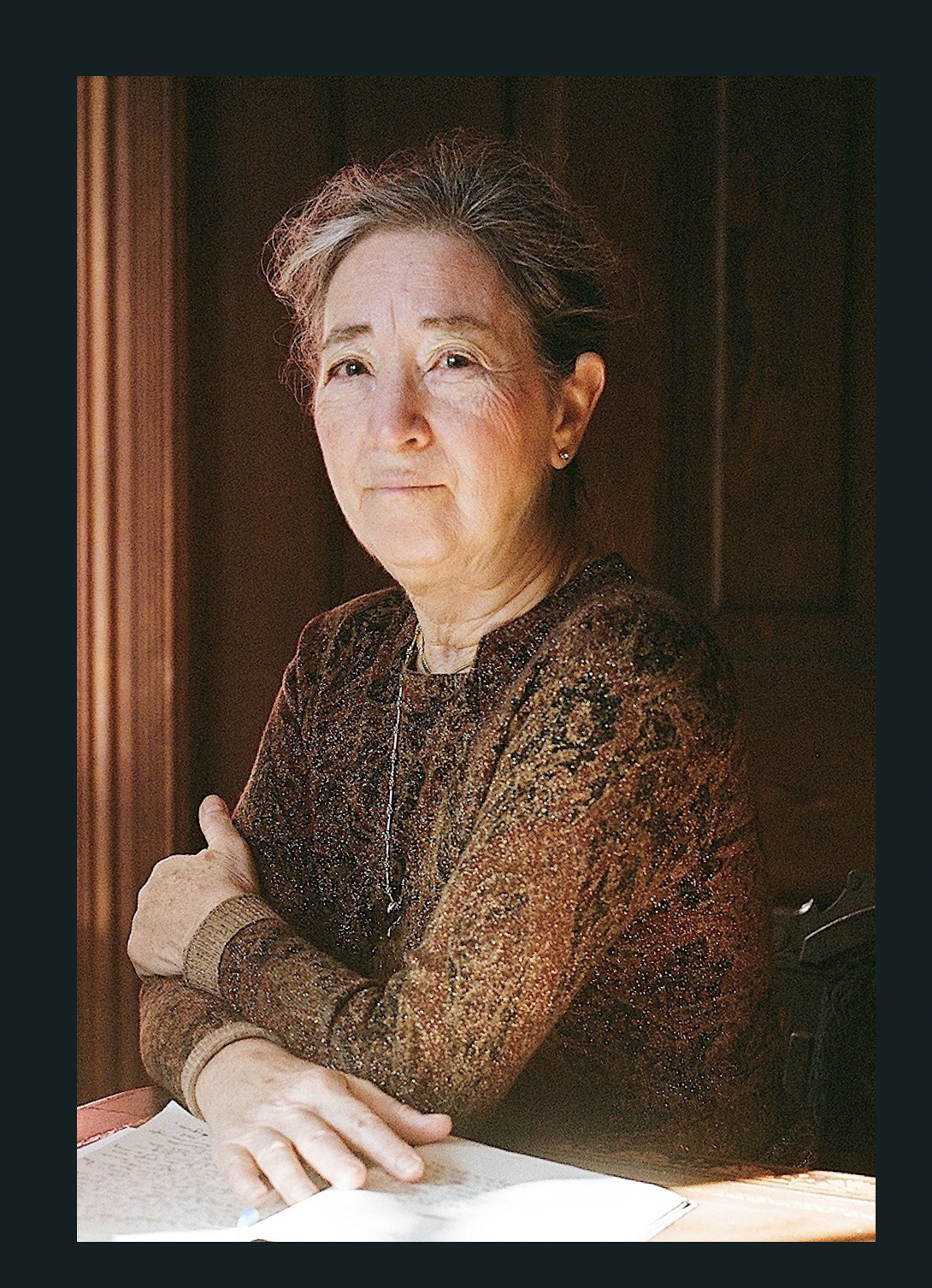

Margaret Gullette considers what various religions and cultural myths have had to say about how old the residents of heaven are. Her provocative and highly original essay was originally posted on The Conversation on Dec. 19, 2019. It’s re-posted here under a Creative Commons license and with the permission of the author.

Many religious faiths propose different versions of heaven as a location: there are walled gardens with streams, flowers, pleasing scents, pretty angels, rapturous music or delicious, accessible food.

But what about us—the once-mortal—who will go on to inhabit the heavenly real estate? What form will our bodies take? Not all religions posit bodily resurrection. But those that do, tend to depict them as young.

As the author of prize-winning books on age and culture, I tend to notice unseen forms of ageism.

I wonder: Is the cult of youth what we really want trailing us into the afterlife?

According to Christian orthodoxy, if you’re worthy of being raised from the dead, you’ll be resurrected in the flesh, not merely as spirit, with a body restored like that of Christ, who died at 33.

In heaven there will be no whip marks, no scars from thorns, no bodily wounds. If eaten by cannibals or bereft of limbs from battle—some medieval people worried about wholeness in such conditions—people would regain their missing parts. The body would be perfected, as the Apostle Matthew promised in the New Testament when he wrote, “The blind receive sight, the lame walk, those who have leprosy are cleansed, the deaf hear.”

In Islam, in the traditional Hadiths—the commentaries that succeeded the Quran—the righteous are also youthful, and apparently male. “The people of Paradise will enter Paradise hairless (in their body), beardless, white colored, curly haired, with their eyes anointed with kohl, aged thirty-three years,” according to Abu Harayra, one of Mohammed’s companions.

The afterlife isn’t all based on sacred text. Folklore, cultural traditions and audience demand also shape its images.

Western art has, over the centuries, located the promise of posthumous perfection in bodies that are youthful. British historian Roy Porter writes that the art of the Renaissance (in which bodies were first portrayed with muscles and motion) showed “rosy-fleshed and even lithe bodies rising elegantly from the earth, in an almost balletic movement.” Think of the muscular, naked bodies in Luca Signorelli’s “Resurrection and the Crowning of the Blessed” in Orvieto Cathedral.

Throughout history, some people died in their 90s, as they do now. But the luck of having lived a long life on earth, with its wisdom and experience symbolically etched on the face and signaled by the august whiteness of hair, apparently did not cross over onto the other side.

In such visions of heaven, there would be no signs of our ordinary mortal passage. No wrinkles. No disability. No old age. “Perfected” means never having grown up even into the middle years.

Ageist and ableist, these traditions promote cults of youth. The New Testament, the Quran, the Italian Renaissance, the Romantic era—all sing the same decline-oriented, exclusionary song.

Jump to the myths of the modern world, and the aftercare of the fit, juvenile body remains precious. In vampire stories, for example, the undead bloodsuckers appear young and attractive. When their true age is revealed, it turns out that they’re often thousands of years old.

“Who wants to see old ghosts?” critic Martha Smilgis wrote in a 1991 Time feature about a recent spate of films that featured young, lithe actors populating the afterlife. “Hollywood wants to remain forever young,” she continued, “and what better way than to extend yourself into another life?”

In the award-winning Black Mirror episode, “San Junipero,” the fantasy of forever young becomes a reality: the dead can upload themselves into a simulation to live out their afterlives as their younger selves.

In other television shows about the afterlife, one way to avoid old ghosts is to simply have the characters all die young. And so in series like Dead Like Me and Forever, freak accidents on earth ensure the resurrected are fit and attractive.

Because we now live in an age of longer, healthier lifespans, and because I’m in my 70s, I’m nonplussed by seeing the cult of youth persist.

People I know in later life are healthy. Some are handsome. Unlike the great unwashed of previous epochs, old people too now bathe. We brush our teeth, so we don’t lose them before 40. Syphilis, in the rare event that we contract it, can be cured. If we have partners, we enjoy sex.

I can understand idealizing youth in this life, but only by considering the ageism that people endure in the workplace. Sure, a midlife job seeker, desperately unemployed, tweaks his date of birth on his resume because he is considered “too old” at too young an age. A woman dyes her hair and gets a little Botox for the same reason.

But in heaven too, where capitalism is gratefully left behind? Surely part of the Rapture is not having to depend on a boss and a paycheck. You can’t be fired, downsized or made redundant. If heaven means nothing else, it works like a good labor union, assuring blessed tenure.

So might we disrupt the ancient, adolescent fantasies that, translated to our contemporary era, seem so anachronistic? I am no longer a teenager. I have put away on earth—as it should be in heaven—the peer pressures, the showy, embarrassing décolletage, shaving my legs, the comical hair styles and the beach-blanket, boozy fantasies of the hourglass figure.

My earlier face would look weird to me were it suddenly to appear tomorrow over the bathroom sink. If heaven were furnished with mirrors—an unlikely scenario—I am certain I would want to behold the face I have now. Whatever its earthly faults in the eyes of Hollywood plastic surgeons and the tiresome fashion magazines, it has the virtue of familiarity.

Heaven is supposed to be the entrance to a fuller, or better, future life—what mortals fail to obtain in the real world. Does that now mean Club Med for young people? Fort Lauderdale at spring break? With more clothing? Or perhaps less?

Mormons are promised that they will spend eternity with their kin. For many people now, paradise is, more than anything, a place where we will meet loved ones. Often, a beloved parent. I would have no interest in a heaven in which my mother appeared to be 33, when I scarcely knew her as a six-year-old. Nor would I want her to look six decades younger than I do, were I to arrive in my 90s.

She died at 96, and I want her to have the face I loved in her very old age. There she would be, still smiling at me benignly, as she does in a photograph I see every day of my aging-into-old-age life.

Heaven can keep the pleasant streams, the divine choirs and the luscious apricots. It can heal us of pain. We can be loved for who we are. If all that, who needs to be younger as well? I believe our dreams of the afterlife need to challenge the idée fixe that only the appearance of youth is valuable.

Some of us with longer lives don’t think it perfection to have the signs of who we are now erased for eternity. We have a finer dream of human solidarity.

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.