Frank told his caregivers’ support group, “I finally got my wife, Millie, to agree to see the doctor about her forgetfulness. He gave her a quiz to test her memory. Millie didn’t do so well, but the doctor said, ‘It’s just a little dementia.’”

He continued, “I feel better. Thank goodness, it isn’t Alzheimer’s!”

Frank’s dread of Alzheimer’s is very common. Common too is his doctor’s avoidance of the “A word.” He instead couched the diagnosis in terms he deemed easier to take.

Or perhaps he was just being honest. If the only test the doctor performed was a Mini-Mental, a widely used screening exam that measures a decline in cognitive function, “a little dementia” is all he would know at this point.

But to halt the diagnostic process there is unethical, not only because the patient and family have a right to a definitive diagnosis, but also because some forms of dementia are reversible. You want to identify one of them right away. The sooner you treat them, the better.

It helps to be clear about what “dementia” is and is not. It’s not merely a euphemism for Alzheimer’s disease (even if it is used that way). It’s not a milder form of forgetfulness.

Dementia is a decline in cognitive skills: thinking, memory and perception. The symptoms can be caused by many different diseases. Alzheimer’s disease is one—the most common. Vascular disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and frontotemporal disorders are other common causes of dementia. (Other problems—like thyroid disorders or a vitamin B12 deficiency—can cause similar symptoms.)

So while Alzheimer’s is dementia, dementia isn’t always Alzheimer’s.

(In my blogs, I alternate using “Alzheimer’s disease” and “dementia” to avoid annoying repetition. I also do it to make clear that the situations and problems I discuss pertain not only to Alzheimer’s but to all the diseases that cause the collection of symptoms we call “dementia.”)

Because there are many possibilities, a thorough assessment is essential to find out what is causing the symptoms. People frequently ask, “What does it matter when nothing can be done about it anyway?”

It does matter. Here’s why:

- Foremost, as I mentioned, it might be something reversible.

- For many people a diagnosis—even of Alzheimer’s—comes as a relief. After he learned he had Alzheimer’s, Martin said, ”You know, I thought I wasn’t trying hard enough to get things straight. Now I know it’s not my fault. And it’s not that I’m crazy.

- Patients and caregivers alike adapt and cope more easily if they have good information about what they are dealing with and what to expect.

- There are treatments that–though they don’t stop the progression of the disease–improve symptoms temporarily in Alzheimer’s and dementia with Lewy bodies. They are less effective in other dementias. And they’re most effective in the early stages.

- Some other medications are contraindicated in dementia with Lewy bodies. Patients and care partners must be informed if they are dealing with that disease.

- Often, people with dementia are more hopeful and feel they are making a contribution if they can participate in a clinical trial. However, to enter a trial, you must first have an accurate diagnosis.

How do you get a thorough assessment and diagnosis?

The search can start with your primary care physician. However, if, like Frank and Millie’s doctor, he’s not proactive, you will need to pursue a more thorough assessment.

But let’s say your primary doctor is on top of things. Maybe she’s even a geriatrician, a specialist in the care of older people. She will start with a medical history and ask for a description of symptoms and how they affect the daily life of your partner.

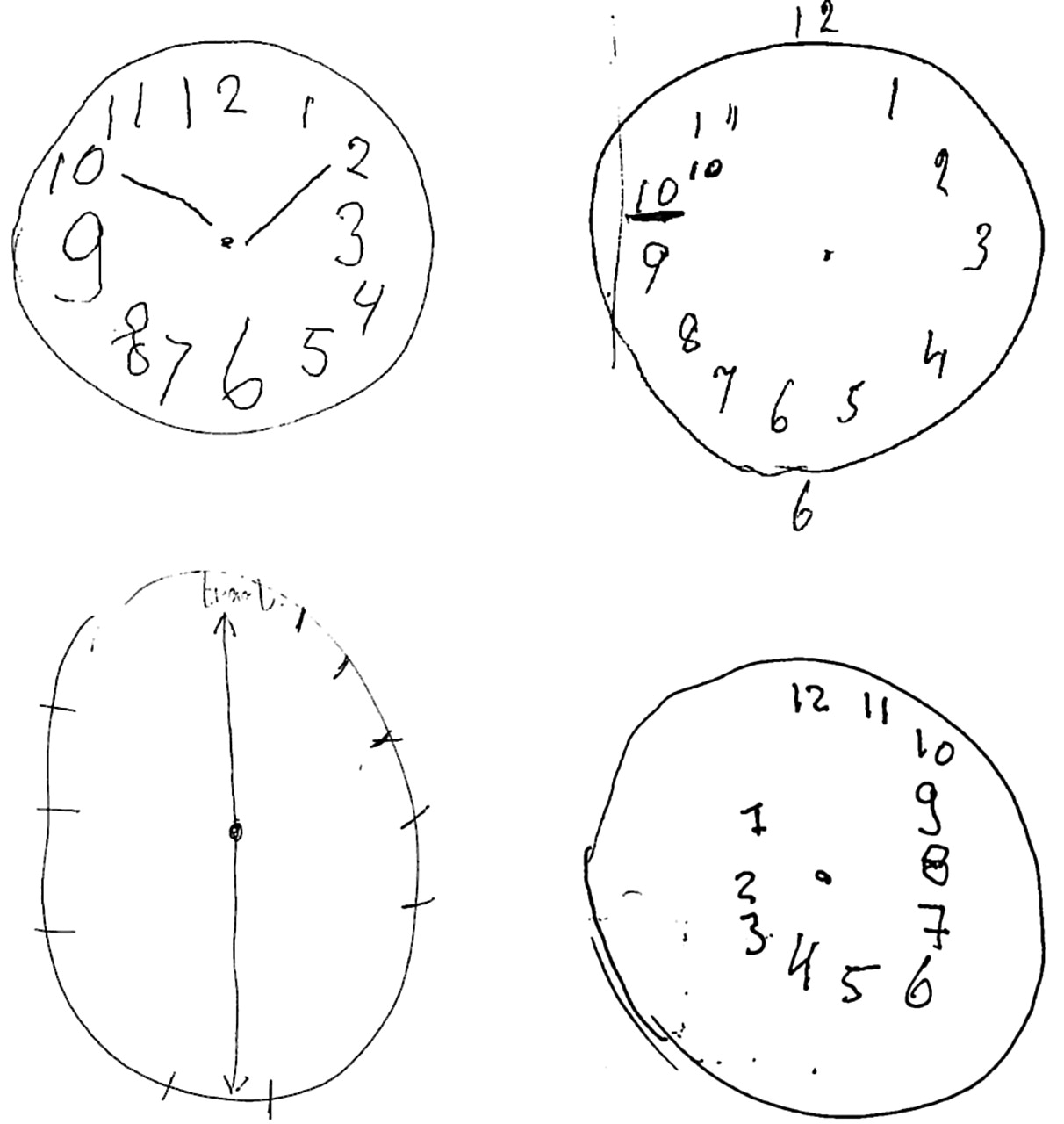

She will do a medical exam, and a brief mental status test like the Folstein Mini-Mental State Exam or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Your partner’s score will indicate whether she (or he) has some decline in cognition. It doesn’t reveal a cause.

The doctor will order tests of blood and urine to check for some conditions that can cause a change in cognitive ability but, with treatment, are reversible: thyroid disorders, vitamin B12 deficiency, use of certain medications.

She will screen the patient for depression because the symptoms of depression can resemble dementia. If that’s all or part of the problem, anti-depressant medication can improve both mood and thinking.

If the doctor finds no reversible cause for your partner’s cognitive decline, she should send both of you on to a neurologist, a specialist in diseases of the brain, to test reflexes, gait, and balance—things that could indicate certain parts of the nervous system are affected.

The neurologist can order and then interpret a brain scan—usually an MRI—looking for signs of strokes, a brain tumor, fluid accumulation, brain atrophy—all of which could cause the symptoms of dementia.

Kerry learned the benefit of brain scans. Her husband, Mike, couldn’t hold on to information for more than 10 seconds, had great trouble walking and fell repeatedly. Kerry thought he was losing the ability to walk because he didn’t walk enough, but a brain scan revealed that he had normal-pressure hydrocephalus—a buildup of fluid in his brain. He had surgery to implant a shunt to drain the fluid, and within months his memory and walking were nearly normal.

If the MRI scan reveals nothing, but your partner’s score on the mental-status exam showed a decline in cognition, she (or he) will need neuropsychological testing to get a more specific diagnosis.

For this, a psychologist who specializes in the connection between the brain and behavior and function gives a large number of tests to the patient over a period of several hours. This can be grueling.

Each test focuses on a specific cognitive function—the very ones that tend to decline in dementia. It follows that those who do have a form of dementia are going to run into some trouble on the tests. Some break down and weep.

Neuropsychologists are trained to be encouraging and help people relax. They will halt a test that is proving too challenging. Naturally, the test givers vary in their ability to put people at ease. And the test takers vary in their nervousness and their willingness to cooperate. My friend, Nigel, when he heard I was writing about this, told me that when he took his wife for the tests, she refused to cooperate and got up and walked out.

Even the brief cognitive screening tests (e.g., Mini-Mental) that the primary doctor or neurologist repeats once a year come to be dreaded by people with dementia. They, like any of us, hate to be confronted by their failures. Charley made his wife drill him on what date it was and what town they were in (questions included on the test) as they drove to the doctor’s office. Other people with dementia simply refuse to go to the doctor.

The usefulness of these brief screening tests declines as the disease progresses, so I suggest that care partners talk to the physician about discontinuing them after a couple of years.

The information derived from the more extensive neuropsychological tests can be very valuable. It indicates where a person’s brain is working well and where it is not. The pattern of disease it reveals adds more certainty to the diagnosis. And it helps families plan care by revealing where the individual needs the most support and where she (or he) can still function independently.

If your partner is not getting a thorough assessment through your primary care physician, try to find a local geriatrician or neurologist with a lot of experience with dementia. Or check to see if one of the National Institute on Aging’s 32 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers is nearby. You can’t do any better than to go there. They are located at major medical institutions around the US. Not only will the physicians be the best in the field, but they will be in touch with the latest research and treatments, if not actually conducting that research themselves.

Go here for locations of the centers. Appointments may need to be scheduled months ahead. Not only are they in demand, but your partner will need a block of appointments to cover all the examinations and tests.

Your next best bet is to go to a nearby teaching hospital. See if they have a memory center. You should find a good diagnostic program there.

Several types of blood tests for Alzheimer’s have been developed recently and look very promising. Their reliability needs to be proved, but assuming it is, they should be widely available in around five years. That will change the diagnostic picture a lot, but not completely. People will still need to be tested for any additional factors that might be contributing to their dementia, like vitamin B12 deficiency or vascular disease. And the neuropsychological tests will still be very helpful in shedding light on where people need help and what their remaining strengths are.

Testing—current and future—gives families a better idea of the near-term prognosis and the long-term. When we got my mother’s diagnosis, her prognosis set in motion big changes for her and for me because it was clear she could no longer drive a car or live alone.

On the other hand, I know a couple who, immediately after her diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and given her prognosis, drove across the country and visited all their favorite National Parks.

Pursuing a diagnosis—and hoping it isn’t of Alzheimer’s, the word no one wants to hear—is not opening Pandora’s box. It is opening the door to the opportunity for help and understanding. It helps you and the person you love make the best of what may be the biggest challenge you will face together.

Maggie Sullivan has come to know Alzheimer’s intimately. She was caregiver and advocate during the eight years her mother lived with the disease. For the past 30 years, she has facilitated caregiver support groups for the Alzheimer’s Association, learning from the experience of more than 300 members of those groups. The opinions she expresses here are her own. Maggie is also a writer whose essays and articles have appeared in the New York Times and elsewhere.