This thoughtful blog about a change of heart was originally posted on both Next Avenue and Forbes on May 12. It appears here with the permission of the author.

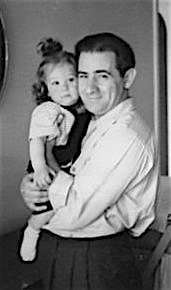

My father had plenty of habits that irritated my mother. But nothing irritated her more than “Marty being cheap.” As a child, I didn’t understand it either.

For instance, my father turned off the lights in rooms that people had just left. Sometimes we were leaving just to come right back in, but whenever he was home, he would march across the little hallway from wherever he was at either end of the house to click the light switches down. Did he like a dark house?

With the lights off, the forest-green end of the house was as dismal as a real Hansel and Gretel woods. My mother would march right back from wherever she had been to defiantly flick the switches up.

My father also saved things. He wore the same, plaid, flannel shirts year after year, one on top of another, even indoors. In the basement shop, when I was invited, he took long, thick, crooked nails that had been pulled out of boards with the claw end of the hammer and smashed them with the fat, butt end, so they straightened out like new.

He saved rusted nails, which had turned a delicate, copper color I liked. Each size went into its own unmatched, little, glass jar: screws, screw-eyes, all the iron nails: the tenpenny, brads, roofing nails, slender, white, finish nails and even some upholstery nails with stubby shanks hidden by golden, curving, indented tops.

But the frugal habit my mother mocked most was my father’s taking the little, bitty soap ends and mashing them together, so they made a small, irregular cake or many-sided, oily, squashed muffin.

He didn’t explain to me why he was doing any of those things. He didn’t explain anything, except, rarely, American politics. He was a silent man.

Maybe in those days, my mother flattened him. But she was a good mother to me, and you don’t judge your parents when you are still so young it’s difficult to tell them apart. Later, when I was married, they came to visit to say they were a happy couple now. My mother, as it were, apologized. She said gaily, because it was all in the past, “I didn’t let him be the captain of his own ship.” They had a good year before he got sick with ALS.

As an adult, I used to tell friends those amusing, childhood stories about my freaky father—straightening bent nails, turning lights off, saving soap ends. People recognized he did those things to save money.

In the middle class, where my husband and I had slowly risen to occupy a fairly secure place, saving money had begun to seem odd. It was “cheap,” just as my upwardly mobile mother had said, even before the postwar boom really got started lifting our boat.

My generation’s goal, as we were moving up economic ladders, was to spend on visible objects, showing taste as well as means.

But over time, I noticed that as I told the stories, they had lost the tinge of being amusing foibles. They began to edge toward being about thrift. Conspicuous consumption had seemed cruelly elite during the Great Depression, which marked both my parents, though in opposite ways.

Likewise, after the Great Recession of 2008, waste of any kind began to seem excessive, ostentatious, brutal and stupid. Saving became not a mere trend, but a value and a virtue of those who could manage it. The planet cannot take the rapid, steady diminution of its resources forever.

Plenty of people are replicating some of my dad’s frugal habits. Anyone with any sense now wants to save electricity, because so much of it still comes from fossil fuels. Everyone goes around smoothing down the dimmers.

I’ve come to see differently what I once thought of as my father’s eccentricities. I’ve come closer to him in spirit.

Since he gave me his jars, my own basement shop has held his nail collection and I draw on the legacy.

Just recently, when I mentioned the soap ends, a close friend said with a smile that was only slightly embarrassed, “How do you do that?”

“Oh, it’s quick and easy,” I began. “You get a few slivers wet and soft and slimy, and you crush them and press them and rub them around until they hold together. It feels so nice.”

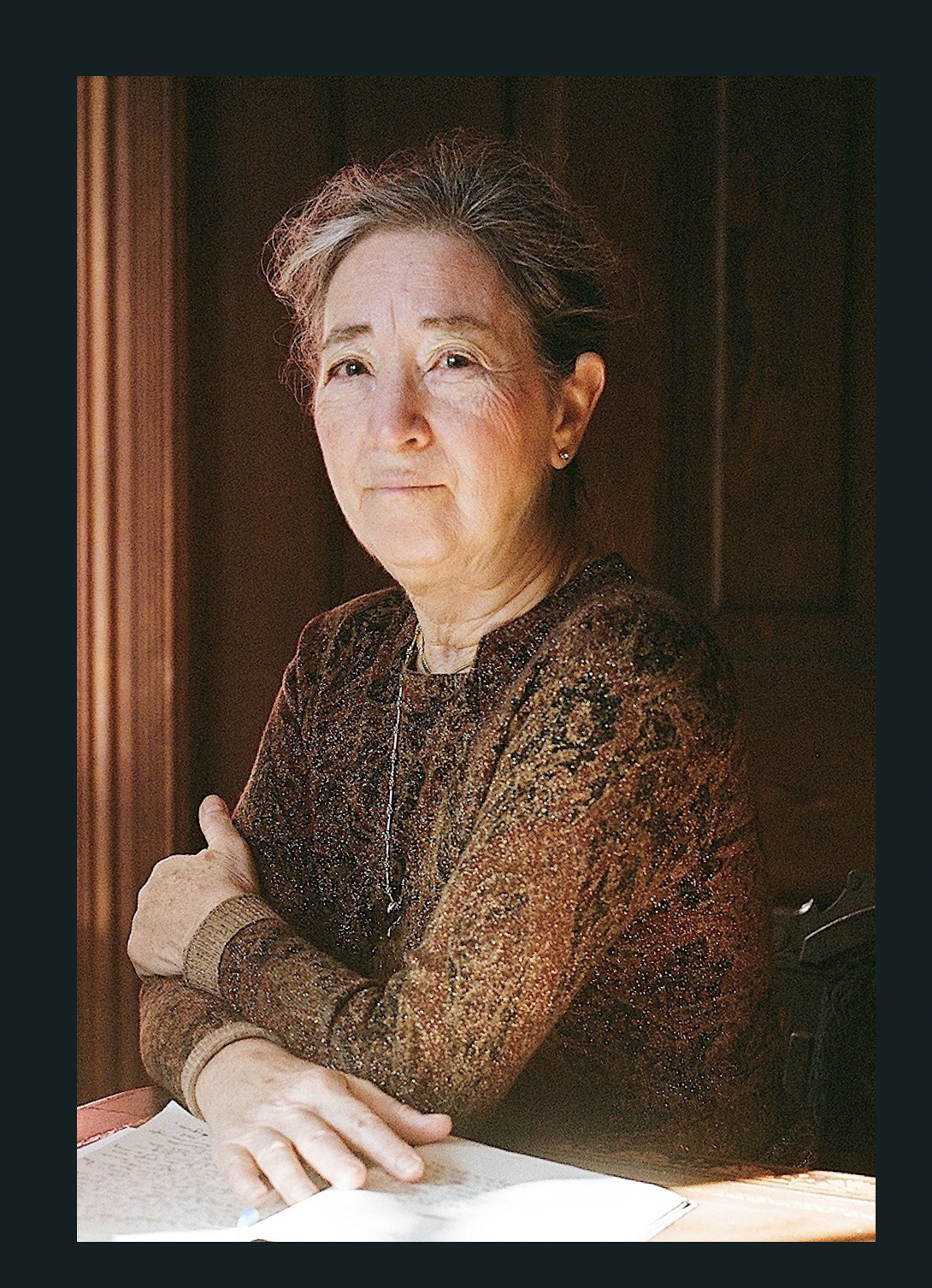

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.