This thought-provoking piece was first published in the Boston Globe on October 11, 2019, and is posted here with the author’s permission.

In a nation grappling with growing inequality, stagnating social mobility, crushing personal debt and crumbling job security, efforts to set America’s generations against one another persist. Don’t blame the system, blame the “greedy” boomers. Or the “slacker” Gen Xers. Or “entitled” millennials. But who gains from such discourses?

Efforts to foment that warfare, intentionally or not, serve specific agendas. Numerous writers warn that age-group hostilities are “coming.” And then, pitting generations against one another, aside from their war metaphors, writers reach for doomsday predictions, lachrymose empathy for “our kids” and questionable data. All this relies on the invention of mendacious attributes, conferring on millions of diverse people implausible character flaws or virtues. Karl Mannheim, the 20th-century sociologist known for explaining the uses of generational units, would be rolling over in his grave.

Here is the hidden history of a perverse political discourse: it started with the so-called boomers. As they aged toward peak midlife wages in the 1980s, they got saddled with a reputation for being rich and greedy. The media concocted a lie that made it seem as if they wouldn’t ever need Social Security.

Bill Gates was born in 1955. That makes him what is commonly called a boomer. Rene Lavoie was also born in 1955. The [Boston] Globe recently recounted the problems that led this white Army vet to spend time in Boston’s homeless shelters. According to the principal investigator of a recent study, Dennis Culhane, many people of Lavoie’s age are indeed part of a boom—”a boom in aging, homeless people.” They were “less well-educated people who faced economic challenges in their youth—falling wages and rising housing costs—and never recovered financially.… Now in their 50s and 60s, they are biologically older than most people their age.… The average lifespan for a homeless person is 64.”

Unlike Gates’s co-billionaires in the .01 percent, 29 percent of people 55 and over have nothing at all saved for retirement, according to the Government Accountability Office, and many of the rest have little. Ageism in the workforce is one reason they lose a job and then can’t find an equally good one—or find any work at all. Boomers are often treated as “deadwood.” Corporations drop them by the thousands. Even Xers are now old enough to be at risk of having their resumes discarded. When people suffering from middle ageism stop looking for work, they are omitted from the unemployment data. At midlife, some submit to deaths of despair.

Succeeding cohorts (all containing the same disparities—of class, race, gender and education) have also been treated as if they were a single human with a character flaw. During the 1990s recessions, when the so-called Xers couldn’t find work, they too were branded with a slur—“slackers”—while boomers were represented as the horde of bullies who held onto all the good jobs.

The baleful technique is still at work today. Given the same problem—lack of decent jobs for all ages, especially people without college degrees and people over 50—it’s the turn of the millennials. One of them complains about the stereotypes, defensively, in Vox: “We demand participation trophies, can’t find jobs, and live with our parents until we’re 30.” His response is to bash—you guessed it—the boomers, who “have a ton of maladaptive personality characteristics.”

In the Atlantic, pundits Niall Ferguson, from the Hoover Institution, and Eyck Freymann defend millennials because their “early working lives were blighted by the financial crisis”—but ignore how home foreclosures, sluggish growth and job losses also blighted people around Ferguson’s own age (55).

Millennials are supposed to be so ignorant and cruel that they would dismiss old people’s needs because of the boomers’ alleged wealth. “Cutting old-age benefits for boomers would be an easy call if millennials are anywhere on the line of fire,” write the original concoctors of the age-war distraction, Neil Howe and William Strauss, in their latest, pandering assault, Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation (2000).

We frequently hear that our elders’ retirement needs will “break the bank” despite their lifelong pay-ins. If Republicans manage to destroy the whole system of social trust, cutting Social Security could indeed be one of the dire outcomes of the lies of generational warfare. Otherwise, experts say, its financial failure is not remotely in the cards. For families it has always been the most popular government program, because it provides a measure of dignified independence for older people and a measure of relief for their adult children.

Younger people should support the expansion of Social Security for another reason, writes one millennial who doesn’t take the bait. Nick Guthman argues in The Hill that because of student debt, “Millennials and Generation Z will need Social Security even more than our parents and grandparents do.”

The [Social Security] 2100 Act, now before Congress, would raise the cap on taxable-wage contributions. Conservatives reject this easy fix, but it is overwhelmingly popular with the public.

Manipulating cohort characteristics damages far more than attitudes toward Social Security, bad as the effect of that contrived skepticism could be. Blaming an older generation that is already maligned allows many real perpetrators to smugly hide from their irresponsibility. Will the climate movement find youngsters blaming the boomers for ecological destruction, because some drove big cars? Wouldn’t it be better to turn on the CEOs of Exxon, who hid the dangers of burning fossil fuels that their scientists discovered so thoroughly that few of us knew to stop flying?

Persistent precarity is indeed the historical issue that is obscured by these discourses. The fact of American decline is this: most people in each generation have had it worse than their parents. According to a report on The State of Working America (2012), the United States lags behind its peer countries in the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) in measurements of father-son mobility. In the United States, the “sons” have been receiving stagnant wages, fewer benefits, jobs in the insecure gig economy. Many women too have lost the progress narrative of rising expectations. That progress narrative, when upward mobility was more widespread, supported the American Dream. It gave hope that democracy would work for increasing numbers.

Don’t blame your parents. Every article manipulating cohort stereotypes lets the government and corporations off the hook for outsourcing abroad, the crash of rust-belt industries, de-unionization and the decades of cascading downward mobility we now endure. You can’t even want to get justice until you know the true sources of injustice.

How do imaginary reputations and hostile emotions get nailed onto struggling groups, decade after decade, in this pernicious way? Naming each imagined age cohort makes it possible. The process is called reification. Naming makes vague, temporal proximity into a thing.

Only the name “baby boomers” had an adequate, demographic and historical reason to exist. These millions were born (from 1946 to 1964) of the relative affluence that spread after World War II. Their numbers did give them unifying experiences as they grew up—made their elders build new schools for them, made their working lives more competitive. Now they are confronted by a president who, after promising not to, is cutting their security and health care in devious ways.

But, even undergoing historical events together, age-peers don’t build the same memories, share the same beliefs, behave uniformly. During Vietnam, some young men were conscripted into the war while others fought to end it. Stark differences likewise mark the current group of young people (unimaginatively called “post-millennials”). Some of them are woke and ready to take on racism, sexism, homophobia, gun control, global warming. At the same age, neo-Nazis are setting fire to synagogues.

Once cohorts are reified by name, the labels become dog whistles. Envy and fear can divide a nation and abet destructive political changes. Malice can turn one generation against another.

We could mitigate the divisiveness. Editors could stop soliciting age-war articles by second-rate phrasemakers. We ordinary people need to defy the lies and build intergenerational bonds. Let us understand that capitalist and neoliberal choices have worsened life, for decades, for every later, unequal subculture. And a comforting, unifying, cross-age coalition should eject politicians unwilling to maintain and repair our precious communal institutions.

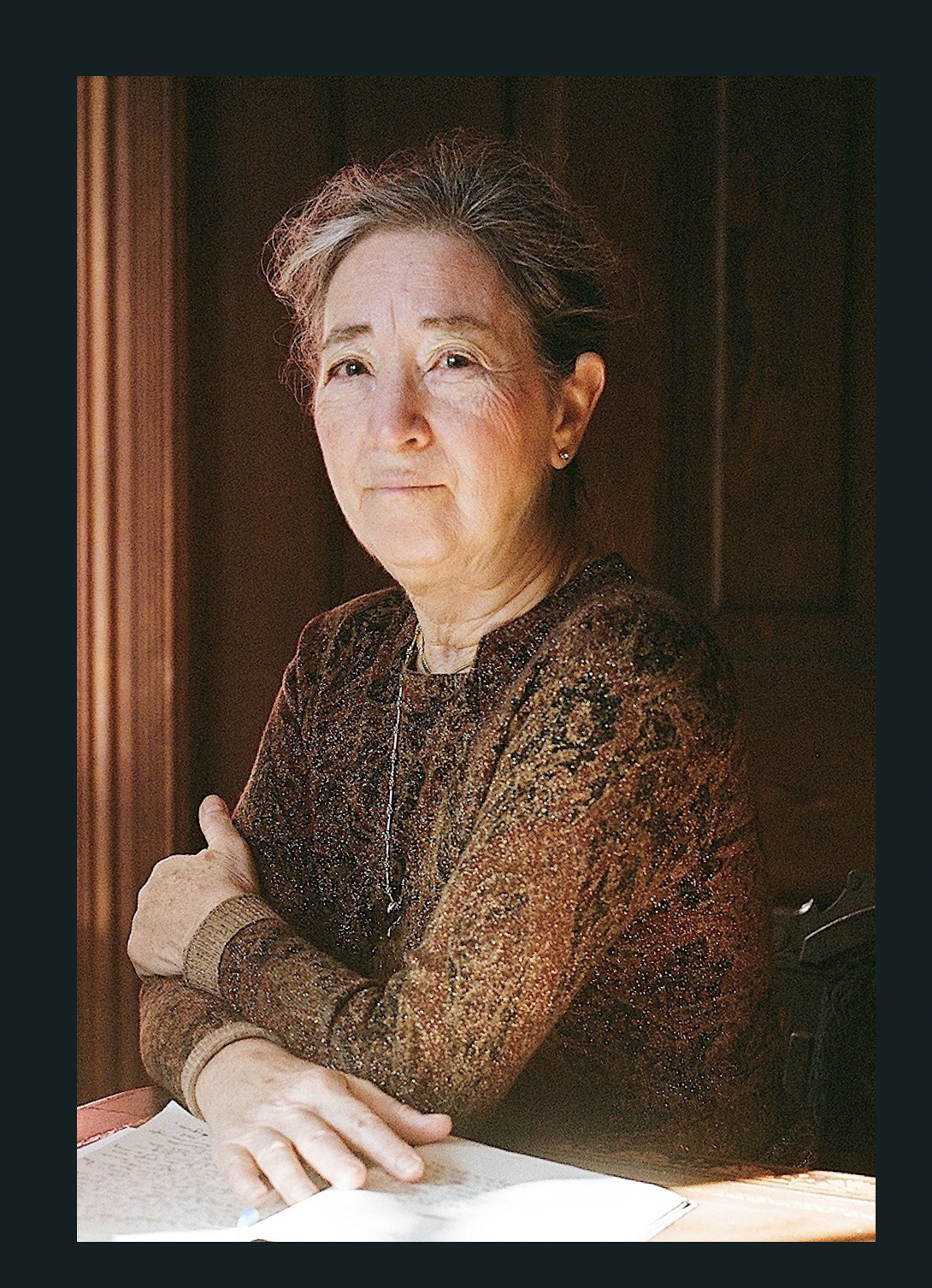

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.