Venice at the opening of the Biennial international art fair is crowded, gaudy, expensive, magical and, it turned out, very grandchild-friendly.

We were there partly to babysit, to help out our daughter-in-law, Yto Barrada (who was invited to exhibit at the Biennial, a great honor) and our son, Sean (who was preparing for an acting job in Beirut). But my husband, David, and I were also there to enjoy our third trip to Venice together. We were hoping to manage child care and a romantic vacation simultaneously.

It didn’t hurt the joint project that Vivi, our granddaughter, was already 5 years old and a charmer—talented and sociable. Our landlady said, “Ciao, bellissima,” every time she saw her. Our local ice cream seller gave her extra scoops. The best mask-maker, who gave us a demonstration, remembered Vivi’s name when we returned. When Vivi selected three glittering, pink pieces of Murano glass at an antiquarian’s, the owner strung them and added a clasp as a gift.

Vivi loves languages and drawing, as we do. It was easy to walk her around to places we wanted to see. At the Biennial, we all grooved on installations. We watched the candles burn on Urs Fischer’s realistic wax sculptures. Vivi watched her mother’s video, Hand-Me-Downs, which is about her other grandparents, with the same interest we did. David took her up into the scarily flexible Bamboo Tower built by the Starn brothers at Peggy Guggenheim’s. I watched her face light up in front of a store that sold ballet slippers and tutus.

She quickly learned Venetian lore and relevant Italian. “We can’t get enough of that winged lion,” she said, after we had observed the symbol of the city in the Piazza San Marco and on every trivial consumer item that tourists might want to buy. Five-year-olds being avid for all knowledge, we easily taught her the name of the special wooden fixture that holds a gondolier’s oar, the forcola—as well as gelato, grazie (adorable everywhere) and cinghiale (the boar sausage her grandparents seemed to like so much).

Copying from the great painter Carpaccio’s originals at the building devoted to St. George and the Dragon, in one hour she drew three versions of the knight on horseback killing the dragon with a spear through its throat, not omitting the blood dripping down its jaws, the skulls of the murdered victims, and the grateful princess who didn’t get eaten. Meanwhile we were marveling at her artwork in our own ways.

I had managed at the last minute to find two apartments: one for my husband and me, and one for Vivi and her parents. She slept at her parents’ every night, but she would often spend the day with us, have lunch and an outing or eat out for an early dinner. She declared stoutly that she never napped, but on the few occasions when we wanted a nap or a rest, she settled on our old-fashioned, velvet, living room couch with a picture book I had brought and soon fell refreshingly asleep.

Both apartments backed onto the best of the children’s parks in Venice, the Savorgnan, in the Cannaregio district. Once, Vivi was swinging there when a horde of uniformed, elementary school children dashed in, took over a low table, clasped hands and yelled in unison, “Buon appetito a tutti.” Vivi quickly learned it, and it became our mantra before every meal.

Cannaregio also had the most natives, good fresh fruit and vegetable stores and the easiest vaporetto stop for moving rapidly to the other side of the city. Several times, David cooked with wonderful local ingredients for all five of us after the kids’ long workdays had ended. We five ate out, on nights when Sean and Yto were not dining with the international art world, at restaurants where we pretended that a dollar is worth a full euro.

The trip would have been impossible without a stroller—if only because the grandparents carried so much stuff. Basic equipment: hats, sunscreen, water bottles; art supplies for Vivi; camera with telephoto lens for David; the Goy guide to architecture for me.

There was a one-day vaporetto strike, when we heroically had to walk from San Marco to the Rialto to find one of the few water-buses running. Although she staunchly repeated that she would never get into the stroller, Vivi rode. She often wound up after an evening out on the town asleep in its cozy depths. The stroller was also a sine qua non in the old Arsenal where the Biennial is held, because the building must be a half mile long.

Whenever Vivi was in her parents’ care, we two wandered together in more unplanned ways, seeking serendipity. After a satisfying morning revisiting the masterpieces of the little-frequented Correr Museum, we found ourselves lunching there at a second-floor window with unobstructed views of the glories of San Marco, piazza and church, high above the intolerable crowds. The small Correr cafeteria even provided a great decaf espresso.

Strolling through the San Polo district, we stumbled upon a stucco-forte maker, who produces mold-cast reproductions in his curious shop, which was filled with marble dusts in rainbow colors. In an antiquarian’s, we found me a dangerous-looking, onyx and black glass, Murano pin from the 1940s that Theda Bara might have worn.

Together we discovered an untouristy neighborhood trattoria, la Palazzina, with the prettiest pergola in Venice, right on “our” canal, with a view of “our” baroque palace and “our” falling-down church. In the evening, reading our books, we drank Prosecco, poured into our own plastic water bottle by the local wine shop for under $4.00 a liter.

In restaurants, I always chose cuttlefish, octopus or creamy cod butter. David went for fish like branzino, “a striper that has died and gone to heaven.” We came home together at night on the almost empty, slow vaporetto, shoulder to shoulder, choosing our dream palazzo from those that line the Grand Canal abundantly. The times when we two were alone together were more precious for being breaks from caregiving.

We don’t “vacation” well, either of us. We don’t like to be bored in crowds or spend frivolously on things no sooner consumed than forgotten. We long ago learned how best not to be tourists. What suited us better was—for decades before global warming made flying abroad unplanetary—an atypical vacation in one of the wonders of the world.

That time in Venice was the only one when we were responsible for our grandchild, with intervals en famille. We celebrated my 70th and Sean’s 43rd birthdays while we were there, as well as Yto’s success. We can’t think of a better place, or a more practical and memorable way, to have done it all.

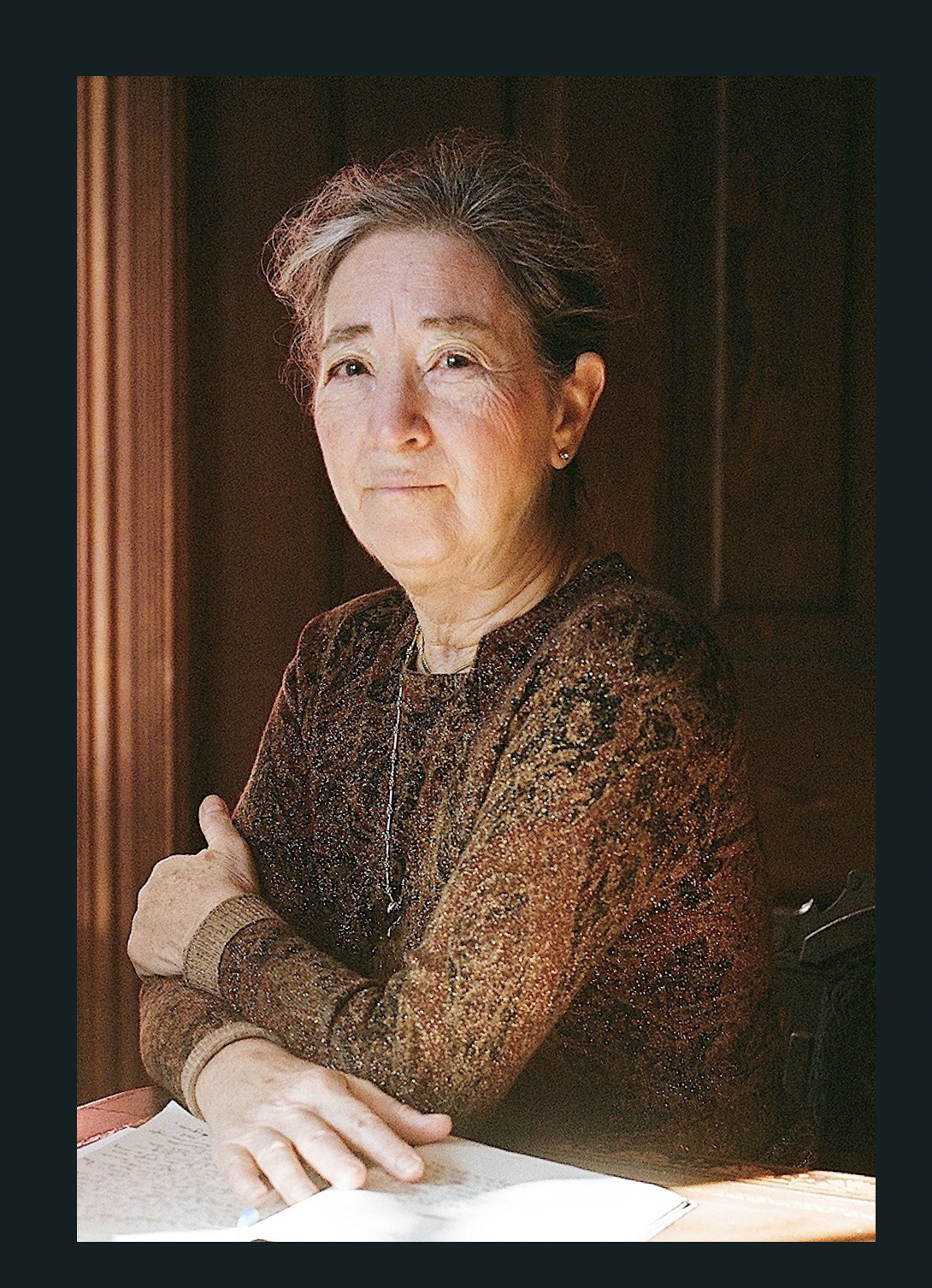

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.