I live in New Jersey, and in April we became the eighth state to permit medical aid in dying. Once the new law goes into effect, people who are terminally ill, who want to end their lives on their own terms, can ask a doctor to prescribe a lethal medication for them, which they can take when they’re ready to go.

Oregon, Washington, Vermont, California, Colorado, Montana and Hawaii already allow aid in dying, as does Washington, DC. Twenty other states are considering similar legislation.

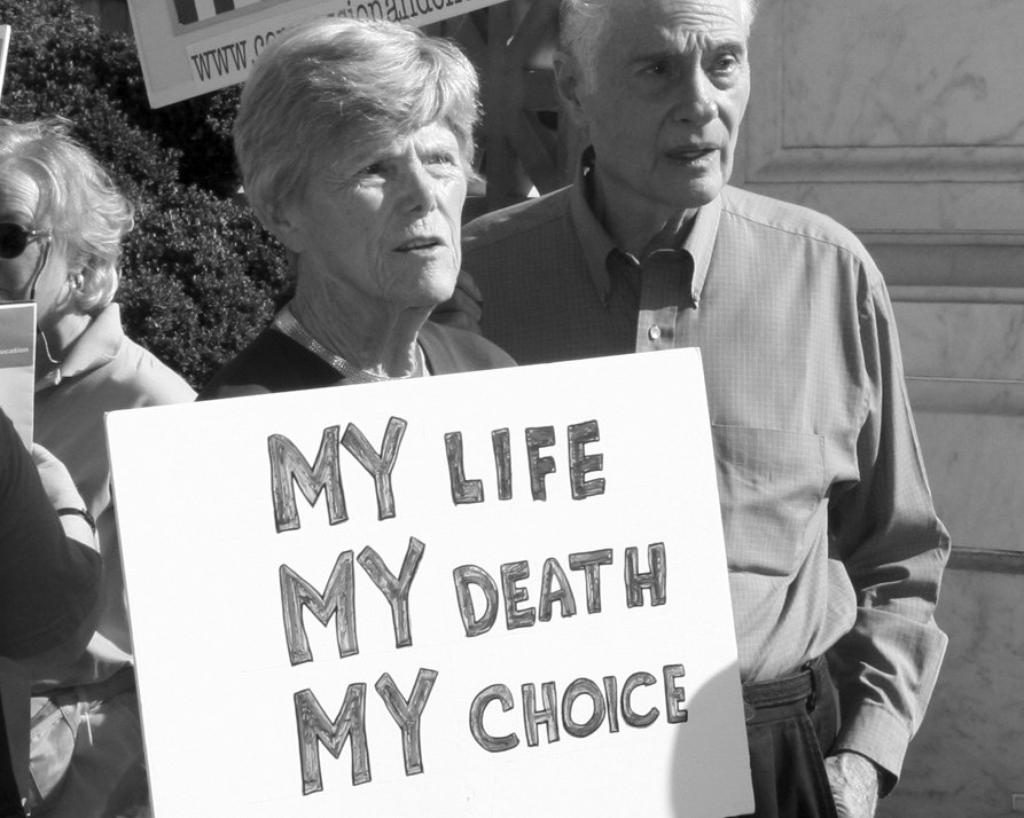

But medical aid in dying is controversial—it took seven years for the New Jersey legislature to pass this law. Opponents argue that aid in dying creates a slippery slope: it makes it possible for greedy relatives or others to pressure vulnerable patients into agreeing to end their own lives. Advocates for aid in dying, on the other hand, say that all of us have a right to choose the way we leave this life.

Personally, I’m glad New Jersey now has this option, but I have mixed feelings about ever using it myself. Still, at my age—84—you do think about such things (unless you’re trying very hard not to), so I’ve done some research. A number of things surprised me.

First of all, if I’m terminally ill someday and decide I’ve had enough, I can’t just pick up a prescription and expect to use it to meet my end, say, a week later. State aid-in-dying laws, which are all very similar, go out of their way to block off that slippery slope, and they do it by creating lots of hoops patients have to jump through before they can get the medication.

For example, I’d have to first find two doctors who agreed that I had six months or less to live. I’d need to ask one of them for a prescription, then wait at least 15 days and repeat the request—and then repeat it yet again in a document signed by two witnesses. In some states, the average time for this whole process to play out is 45 to 50 days. That would leave me lots of time to change my mind and would involve a number of people who could be expected to notice if anyone was pressuring me.

The details of how I’d actually die aren’t as grim as I’d expected. If I were like most patients, I’d lose consciousness peacefully and painlessly within about 10 minutes after I took the drug and I’d die within one to three hours. Still, I note that the medication that’s often used is bitter, and I’d need to get four ounces of it down within two minutes and keep it down. Most people do manage that.

Here are three things more that surprised me. Only about a third of those who go through the process to get a lethal medication actually take it. Apparently, many feel better just knowing they can take control of their death if their situation becomes intolerable. I think I’d be one of those.

And when asked, people who receive a lethal prescription don’t mention the fear of pain as one of their top reasons for wanting aid in dying. Roughly 90 percent cite losses they anticipate: the loss of autonomy—they want to be in control of their own deaths—or the gradual loss of the ability to do what makes life enjoyable. Pain is a concern for just 26 percent.

Also unexpected: when states legalize medical aid in dying, that generally improves end-of-life care, pain management and even cancer care for everyone, not just for those who ask for prescriptions. That’s partly because health systems finally begin to train their physicians in how to talk frankly with patients about all the options for how their lives can end. What’s more, hospices thrive in aid-in-dying states: in Oregon in 2018, more than 90 percent of patients who received lethal prescriptions were on hospice when they died.

Which brings me to why I have mixed feelings about using aid in dying myself. The best way to go, it seems to me, is the way my father went. He died in his sleep from a massive heart attack.

Unfortunately, that’s not something I can arrange for. But there are other options that also seem better than aid in dying, at least to me.

My husband spent the last week of his life in a coma in hospice care. He was kept comfortable by massive doses of painkilling medication. The drugs probably hastened his death, but for anyone who was dying, that was legal well before New Jersey’s aid-in-dying law passed. And that wasn’t a bad way to go.

Some people need to feel they’re in control as they die, but that’s not me. Everybody’s different. I’d much rather not have to pull the trigger myself: to screw up my courage and swallow the medication, knowing what I’m doing is irrevocable, a desperate leap into the unknown. I’d prefer to have other people pull the trigger for me, as I did for my husband.

Even though I don’t like the idea of downing lethal drugs, I do want the comfort of knowing I have an escape hatch if I’m dying and my life becomes unbearable. Consequently, if someday a doctor tells me I’m terminally ill, I’ll probably ask for an aid-in-dying prescription—just in case I need it. That’s my plan B.

On August 15, 2019, a New Jersey state judge suspended the NJ Aid in Dying law in favor of opposition claims that it is unconstitutional. Advocates for the law say they will continue to push for its enactment.

Flora Davis has written scores of magazine articles and is the author of five nonfiction books, including the award-winning Moving the Mountain: The Women’s Movement in America Since 1960 (1991, 1999). She currently lives in a retirement community and continues to work as a writer.