The #MeToo movement is mainly about work situations, and so it should be. Being treated like a skirt—or a headless skirt, depending upon the level of vileness—by a male boss or peer can ruin a workplace, a career or even a life.

But what happens when that form of “attention” stops? Vulgar erotics are indeed a kind of attention, and with them come, or used to come, the invitations to go out for a drink, be part of a group chat or have lunch with a potential mentor. All this could be career-making, as long as the attention didn’t get ugly.

When inclusion stops, it can be perceptible—if you know how to look. An older woman—but not so much older than she was just before—may find herself no longer invited along with the in-group, the up-and-comers, by the mentors and promoters. She may stop being listened to on committees, not get cc’d on e-mails, not get invited to those dangerous conferences where jobs as well as unwanted sex are on offer. Men don’t look up with alacrity when she appears at their office door. Are the promotions or the interesting collaborations not forthcoming for such reasons?

College-educated women start off in their twenties earning not much less than college-educated men earn. At age 45, though, the women make only 57 percent of what the men earn, according to work done by Sari Kerr and published on NBCNews. Women also reach their peak wage at midlife much earlier than men. The age/gender wage gap widens appallingly as everyone grows older. Why? The blame is typically put on us—our marital and job choices, our years out of the workforce for child-rearing. Researchers need to study the factor I am proposing, sexist middle ageism. If this is even partly the case, equal-pay bills passed by the states, or more flextime for men, may not reduce the discrepancy as much as advocates hope.

Commenting on gender- and age-related neglect, Liza Featherstone in the Nation says that “straight men are more likely than our other colleagues to (unconsciously or not) punish us for no longer being vulnerable, smooth-skinned sylphs.”

A Brandeis colleague tells me, “Little did I realize how much of the attention, annoying and otherwise, that I got before [I turned] 50 was associated with my (relative!) youth. It was kind of shocking to have that go away and be replaced by invisibility.”

The comic response to this cult of nubility on YouTube is Amy Schumer’s brilliant alfresco lunch party with Tina Fey and other comediennes as they celebrate Julia Dreyfus’s “Last Fuckable Day.” These women sardonically pretend to be glad to shuck the youthful life-phase of the casting couch. But it means they may never work again. Other women are more explicit about why they are not celebrating. I paraphrase their attitude: “Now I can see the sexually-tinged relationship diminishing. It’s not all gone, but I already feel excluded and anticipate more of the less. I’m not old, just too old. I don’t like it, and I don’t think it’s good for my job or career.” Neglect can be career-breaking.

It can also be heartbreaking. Many women complain about becoming socially and sexually invisible. A therapist writes me, “In fact, I have been hearing the same plaint from my women patients (midlife and beyond) who seem almost wistful that they have never been sexually harassed. They are hurt, wounded in their femininity.” And as they are left behind, they think it’s their fault.

Women who complain about not getting wolf whistles any more make a mistake: they don’t attribute the new neglect to ageism. As a feminist activist, I want women to complain about the new invisibility, but not because they find it personally unflattering. (Myself, I’m happy enough to have my threads of gray, and I have a lover at home who likes them. But I’m not in the workforce, I am free of that tyranny.) Many women cannot see, as C. Wright Mills instructed us to see, that this personal problem is a social issue. Indeed, a cause.

So let’s not trivialize or misinterpret age-related neglect. To overlook others is a prerogative of masculine power. Being excluded comes from the same kind of masculinist, self-centered attitude—“What’s in this relationship for me?”—that brought about the #MeToo movement. It’s the same kind of obtuseness: “What do her feelings matter? What feelings?”

Misogyny brings the bad attention, and misogyny doesn’t end as women get older, it simply takes different forms. The other side of harassment and rape is indifference and disregard or even contempt. First they approach you for the wrong reasons; then they ignore you for the wrong reasons.

Some women do steam ahead in middle age; they get the respect and financial progress that experience ought to bring. They cost employers more as their salaries rise with time, but they survive capitalism’s ageist race to the bottom.

Others, however, become the butt of “middle ageism,” as it should really be known. Middle ageism says that a person is worth less in the workforce because of her age—worth less visually and sexually, but also socially, intellectually and, bottom line, financially. Such demotions may lead us to feel shame for aging past youth. On this charge, we are all innocent: no one can become younger.

“They flee from me who sometime did me seek.”

Read this line by the poet Thomas Wyatt angrily, not nostalgically. Angrily, because being ignored without suspecting the reason may affect your job performance. Middle ageism is a stressor. Shame and humiliation can lead to ill health, depression and despair.

Men can be vulnerable to a similar kind of punishment as they age. Younger men can be seen as sons worthy of being mentored—by men who could never see younger women as daughters. But even “sons” age out. Depending on the field (Silicon Valley, IBM), this can start at 35 or at 50. Middle ageism is destructive to society. It constitutes a vast dehumanization of people, men and women, in their middle years.

Still, a huge gender gap yawns. Women are considered “too old” for the workforce ten years younger than men, on average, if we look at the ages when most men and women sue through the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for job discrimination.

The female victims of Trump, Roy Moore, Cosby, et al., are naming the perpetrators. Some of the guilty apologize and leave their positions; others are fired and shamed. But ageist sins of omission are harder to deal with than overt, biased words and deeds. This form of ageism can be invisible. Your best friend may not observe that you are ostracized at meetings. No one but you will see the shadow falling over the boss’s eyes when you appear, instead of his formerly bright smile.

The answer is not, I would argue, to encourage older women to act or look sexier. If we imitated Jane Fonda—in Spanx and push-up bra at the Oscars this year, at age 80—it would not change the attitude of the bad old boys who lurk in the offices and job sites. It isn’t more sexualization we want in the workplace. We want to be recognized for what we know and can do. We want the masculine cult of youth to change from within. This is an issue of equal treatment in the workplace.

As Liza Featherstone suggests in her recent Nation column, “Asking for a Friend,” one way to respond to the silenced and excluded treatment as an individual is to organize with allies (women friends, gay friends and male friends). Men can be allies. Not every male gaze is fixated on women’s secondary sex characteristics. In my book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People, I suggested a coordinated campaign by small groups, who help the overlooked woman get recognized. “Janine has the experience we need here,” says the friend you’ve planted, turning toward you. “Janine, what do you think?”

Your allies could separately, quietly, step up to the cis-boss who is sending you to Coventry, report your latest good idea or finished project and mention that you seem not to be getting the attention you deserve. “In fact,” an ally says, “I notice that the longer-hired women are never at the staff lunch. Isn’t that odd?” The EEOC has ruled against the bosses who say they need “young blood” or want “younger and peppier” employees, and the discriminated-against can get monetary damages. Warning the boss about middle ageism can be seen as a friendly gesture.

It’s too soon to call out the perps of these subtle forms of sexist ageism. Creating anti-ageist awareness has to be a collective process as well as thousands of individual campaigns. And the first step has to be much more storytelling. The media must publish women’s and men’s narratives, bravely describing the pattern of ugly behavior in detail: how a boss ignored or dismissed them, found a way to demote them or an excuse for not giving them a warranted raise. These narratives must quote the age-related or gender-related hate speech that occurred and tell how the person felt about it. Only when many speak bitterly in chorus about their feelings and their hardships, as #MeToo proves, can change happen.

The #MeToo movement is causing male employers to ask themselves whether employees are disturbed by their unwanted attentions. #MeTooAgainstAgeism, my new hashtag, could teach employers to perceive their unwanted inattention. This bias may be so widespread (and mean, stupid and harmful) that outrage over it could prove unstoppable.

#MeTooAgainstAgeism can be a shorthand for imaginative resistance.

© 2018 Margaret Morganroth Gullette

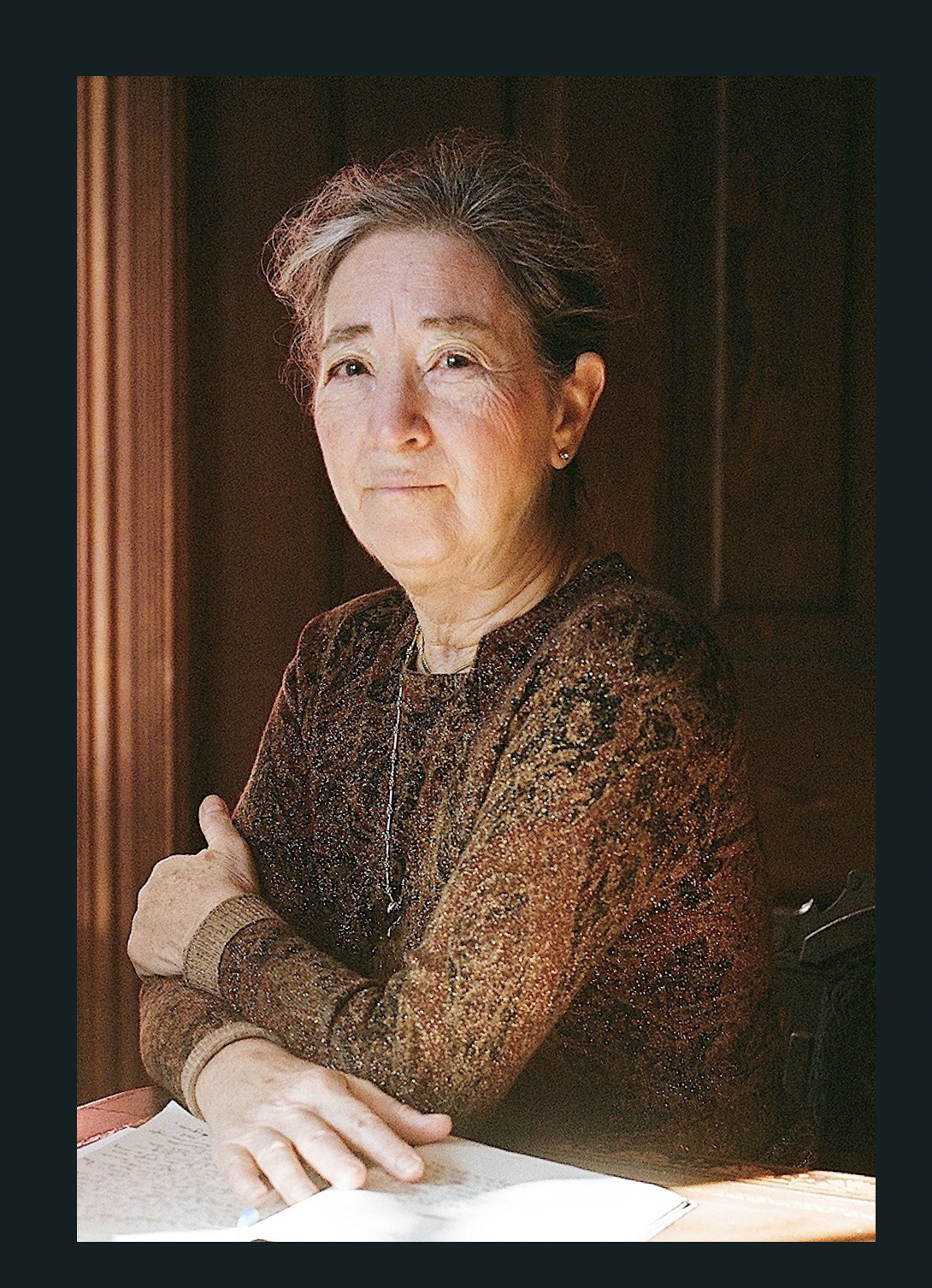

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.