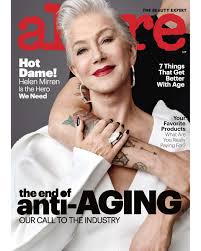

The New York Times Magazine opens every Sunday with an essay about what a given word or phrase reveals about the moment. On September 17, 2017, the word was “anti-aging.” The line at the top of the print version read, “After years obsessing over ‘anti-aging,’ our culture finds itself at an impasse. We don’t want to look older—but we don’t want to feel as if we fear it, either.” The catalyst was the announcement in Allure magazine’s September 2017 issue that the word has been banned from its pages. Editor-in-chief Michelle Lee commended instead “the long-awaited, utterly necessary celebration of growing into your own skin—wrinkles and all.” Huzzah!

But not so fast. As writer Amanda Hess points out in the Times, Allure is still promoting products that promise to make women look younger. The next sentence reads, “No one is suggesting giving up retinol”—God forbid! (It links to an article that begins, “It’s no secret that retinol ticks practically every box in your anti-aging wish list.”)

Titled “The Ever-Changing Business of Anti-Aging,” Hess’s piece is a sharp critique of the rebranding of “anti-aging”—it’s just another opportunity to sell us the same old stuff. Campaigns have changed, over time, from cautionary tales, to aggressive pitches grounded in “science,” to appeals to the easy and “natural.” Notably, attitudes too have shifted.

“As the business of fighting aging has consumed the culture, it has produced a secondary aversion, not just to the signs of aging but to the signs that we’re trying to stop the signs of aging,” she observes.

In other words, we’re moving from anti-aging to anti-anti-aging. Can pro-aging be far behind? Don’t hold your breath. We may nod and agree that we should embrace our wrinkles, Hess concludes, “while quietly understanding that none of us, individually, wants to be the one who actually looks old.”

I do think a more profound shift in the zeitgeist is underway, however. As Hess observes, no matter how glossy the images, flawless the celebrities and clever the jargon, they’re an ever-tougher sell. She writes:

“They must paper over large and knotty things—our discomfort over our own mortality, our deep-rooted habit of valuing women largely in terms of their attractiveness, our growing sentiment that both ageism and gender roles ought to be things of the past—with a cheery promise that a little face cream will help.”

Appearance matters. Adornment pleases. We each have to age in our own way on whatever terms work for us. As one audience member wrote on her “Questions for the Speaker” form at my gig in New Hampshire last August, “I am fine with using anti-aging products. Whatever makes you feel and look good, do it.”

But society’s obsession with the way women look is less about beauty than about obedience to a punishing external standard—and about power. When women compete to “stay young,” we collude in our own disempowerment. When we rank other women by age, we reinforce ageism, sexism, lookism and patriarchy.

In our guts, we know this to be a bad bargain. It sets us up to fail. It pits us against each other. Different forms of discrimination compound and reinforce each other—it’s why the poorest of the poor, around the world, are old women of color. That’s intersectionality, a term coined by black feminist Kimberlé Crenshaw that millennials have grown up with, along with the idea that diversity is a good thing and is here to stay.

In 1970, to believe that women could run Fortune 500 corporations as well as men was a big ask. Fifty years later, gender is a basic criterion for diversity, along with race and sexual orientation. Age isn’t usually on the list —yet. It’s the last socially acceptable prejudice. But when I propose including it, no one says, “That’s a dumb idea,” or “Whoa, let me get back to you on that one.”

We have a long way to go on all those fronts, racism in particular. But if the goal is a society where access to opportunity is not determined by what you look like, gray hair and wrinkles count. Hitching age to the diversity sled makes sense, personally and politically. The ground has been plowed.