Warren Wood is old. He’s proud he’s old. He advertises the fact that he is old by wearing a cap that says UFO in red letters. “What’s UFO?” people ask. “United Flying Octogenarians,” Wood, 86, of Carmel, CA, happily responds.

All members of UFO—an international organization that Wood is president of— had a pilot’s license on or after their 80th birthday. “We still have our wits about us. We can still carry on a conversation,” he says. “We take pride in the fact that we grew old but we didn’t grow old.”

And there’s the crux. You can call them old, but don’t call them old. Because old is bad—even when you’re proudly old. Right?

Well, Pat McGill, 71, isn’t old. She’s seasoned. “Anybody that’s old is just somebody that’s older than me,” says the South Dakota speaker, trainer and consultant.

Ashton Applewhite, 64, is an older—a term she coined in 2012. “It is short. Everyone understands what it means. It is value-neutral,” says the anti-ageism activist, blogger and author of This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism (2016). Besides, “I got tired of typing ‘older Americans.’”

Seniors, older adults, mature Americans—all sorts of terms and euphemisms have been proposed to describe people of a certain age. Nothing has been universally accepted, despite quite a bit of debate, especially over the last decade or so.

“This is a discussion that’s going on in the aging community,” says Karyne Jones, president and CEO of the National Caucus and Center on Black Aging. “Everybody wants a different title, but they don’t want people to label them so that it makes them old.” Her organization most often uses the terms seniors, senior citizens and older workers.

“The question of what should we call this group has been bubbling up more frequently,” says Susan Donley, publisher and managing director of Next Avenue, a PBS-associated website for older people. “I think it’s because people are starting to pay more attention to this group, and this group is starting to get larger.”

By that, she means the boomers have arrived. Now ages 53 to 71, people in the massive boomer generation are getting to be what some might call old, though certainly not old.

In boomers’ lifetimes, old has connoted declining, decrepit and irrelevant. So too, to varying extents, have related words, like senior and—shudder—elderly.

And one thing nobody but nobody wants to do is offend the boomers. These 75 million older adults bring money, power and influence. Newspapers and magazines depend on them as subscribers; local governments woo them for tourism and retirement relocation; independent-living communities (no longer “retirement homes”) need them to move in; manufacturers need them to buy.

But not one of these groups has yet figured out what to call them. All they know is boomers are not their parents, and nobody had better imply otherwise.

The ‘Senior’ Problem

For a number of years, senior and senior citizen were among the most commonly used terms for older people. But “calling Sting [at age 65] a senior citizen just seems wrong,” says Donley, summing up how a lot of boomers feel on the subject. For them, senior implies rocking chairs and golf. And that doesn’t fit how they see themselves.

“Many seniors—especially the younger seniors—don’t like to be called seniors because it reminds them of older people like their own parents or grandparents,” says Manoj Pardasani, PhD, an associate professor at the Fordham University Graduate School of Social Service. “Someone who’s 60, 65 today looks and feels and acts very differently than someone [of the same age] 30, 40 years ago.”

The perceived revulsion against senior is so strong that some service providers, in an effort to connect with these young-olds, have changed their names to omit the term.

Starting about 10 or 15 years ago, many “senior centers” in particular were seeing enrollment rates drop, says Pardasani, who has spent much of his academic life studying these meal-and-activity providers and who’s on the board of directors for Bronx House, which runs such a facility in New York. So some centers decided to change their names and omit the word senior altogether, becoming, for example, “community centers.”

“If society wasn’t ageist, we’d be totally fine with being old.

–Ashton Applewhite

But a funny thing happened. The name changes alone didn’t bring in the seniors, Pardasani says. What did work were major overhauls: centers that changed their programming and updated their facilities, along with changing their names, have been the ones to see noticeable enrollment increases.

As senior centers found, it’s not just the traditional labels that boomers are rejecting but the lifestyle that stereotypically comes with them.

“I’m not my mother’s 70,” says McGill, the speaker in South Dakota. “The baby boomers are going to be the generation wearing the blue jeans. We’re not going to be playing bingo; we’re going to be dancing—and, if possible,” she adds, laughing, “smoking a little marijuana.”

“The longevity boom has created a new stage of life for a lot of people,” Donley says. “If you’re lucky, you’ve got 20 or 30 healthy and productive years that fall after traditional retirement. I think that we’re figuring out as a society what that means and how we take advantage of that—and, as individuals, how are we going to live with purpose? Those are giant questions. I don’t think it’s that surprising that we don’t quite have the vocabulary for it yet.”

Finding the Right Words

There’s no consensus on when these so-called senior years begin. But say they start at 50, the age at which people can join AARP and start getting some “senior discounts.” That would mean society is looking for a term that encompasses at least five decades, from age 50 to 100. “It’s a huge group of people,” says Applewhite, who blogs at This Chair Rocks. (The Silver Century Foundation re-posts selected blogs from Applewhite.) “It’s incredibly diverse.”

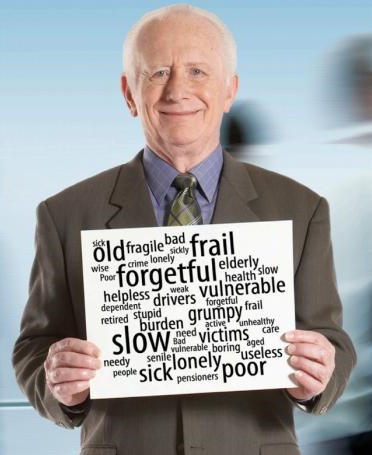

So it’s understandable that finding one term that pleases everyone is challenging. But complicating the challenge is the fact that aging is often viewed in a negative light—as a state of decline. “If society wasn’t ageist, we’d be totally fine with being old,” Applewhite says.

For boomers and their parents and their parents before them, “old age has simply been looked upon as another stage of life but, unlike previous stages, it was viewed as a reversal of earlier growth stages,” wrote Herbert C. Covey, PhD, in a 1988 article about words used for older people that was published in The Gerontologist, the journal of the Gerontological Society of America. “[O]ld age is often associated with decline in attractiveness, vigor, health, and sexual prowess.”

“Once you start to think about aging differently, older adult or other terms stop sounding quite so offensive,” Donley says. “But the problem is the negative perception that those words carry already in our culture. I think that’s why people are looking for something new. What we’ve got is laden with baggage.”

Senior is one of the most-used terms right now. But “no one likes senior, honestly,” Applewhite says. “Senior implies that young people are junior.”

Elders is another option, but it has specific cultural meanings that complicate its use. In some Christian churches, elder is an official designation for certain leaders. In many Native American communities, elder refers to respected older tribe members. “And elder, like senior, implies a higher status than younger people,” Applewhite says.

Elderly is out unless it’s used in reference to frail older people.

Older people has emerged as a top choice in recent years. It’s the term the Silver Century Foundation uses most. It’s value-neutral and doesn’t carry as much baggage as some of the other terms. Besides, “people who won’t cop to being old will more readily cop to being older,” says Applewhite, who opts for her shortened version, olders.

“Perhaps no term will be acceptable until boomers get a little older and start embracing, or at least accepting, their advancing age.

Yet older people is too nonspecific to be the perfect solution for everyone. It leaves open the question, older than what?

The generally accepted best practice is to opt for specificity when possible: people 65 and older, women in their 80s, and so on. But here, another problematic term enters: boomers.

Boomers is specific but to some people, nonsensical. It’s a shortened form of baby boomers, a name for the generation of people born after World War II soldiers came home, between mid-1946 and mid-1964. The infantilizing “baby” is often dropped now—leaving many to wonder what a boomer even is.

“Some people hate ‘boomers,’” says Jones, of the National Caucus and Center on Black Aging. Boomers themselves tell her they don’t understand what the word means—and besides, their parents were deemed the Greatest Generation. “That’s a wonderful example of a term for people who have lived through a great, important time. You don’t want to then be called a boomer,” she says, laughing. “What’s that?”

For the most part, journalists, governments, service providers and manufacturers are left still scratching their heads, trying to come up with the perfect term for their ideal audience. Perhaps it’s out there, in some creative person’s mind, just waiting to be discovered.

Or perhaps no term will be acceptable until boomers get a little older and start embracing, or at least accepting, their advancing age. Maybe it’s normal for people to resist being called old, no matter the word you use—at least for a little while.

“It’s hard to get old,” McGill says. At a coffee shop, a cashier asked one of her family members whether he wanted the senior discount. “He was furious,” she says. “He’s a very kind human being, and he just lost it. For some people, it’s just going to be harder for them to get older.”

That feeling is not exclusive to boomers. “[C]ontemporary older people do not like to use the word old in describing themselves or their membership groups. Many of today’s elderly do not think of themselves as old.” Covey wrote that in 1988.

Wood, the UFO president, was 58 that year. “If somebody had called me old then, I probably would have taken umbrage,” he admits. But now he’s proud to be his age—as long as you realize he’s not old. He’s just old. And that makes all the difference.

Leigh Ann Hubbard is a professional freelance journalist who specializes in health, aging, the American South and Alaska. Prior to her full-time freelance career, Leigh Ann worked at CNN and served as managing editor for a national health magazine. A proud aunt, Leigh Ann splits her time between Mississippi and Alaska.