Sara Ivey, 63, calls it one of the few gifts of cancer: time to plan.

When her husband, Jerald Sluder, was diagnosed with advanced melanoma, the Dallas couple had time to organize his affairs before his death in December 2016 at age 64. In addition to drawing up a will and advanced health care directives, they assembled a list of login information for his email and social media accounts as well as his banking and investment accounts.

Had her husband died suddenly, Ivey said, managing his online estate “would have been a nightmare upon a nightmare upon a nightmare.”

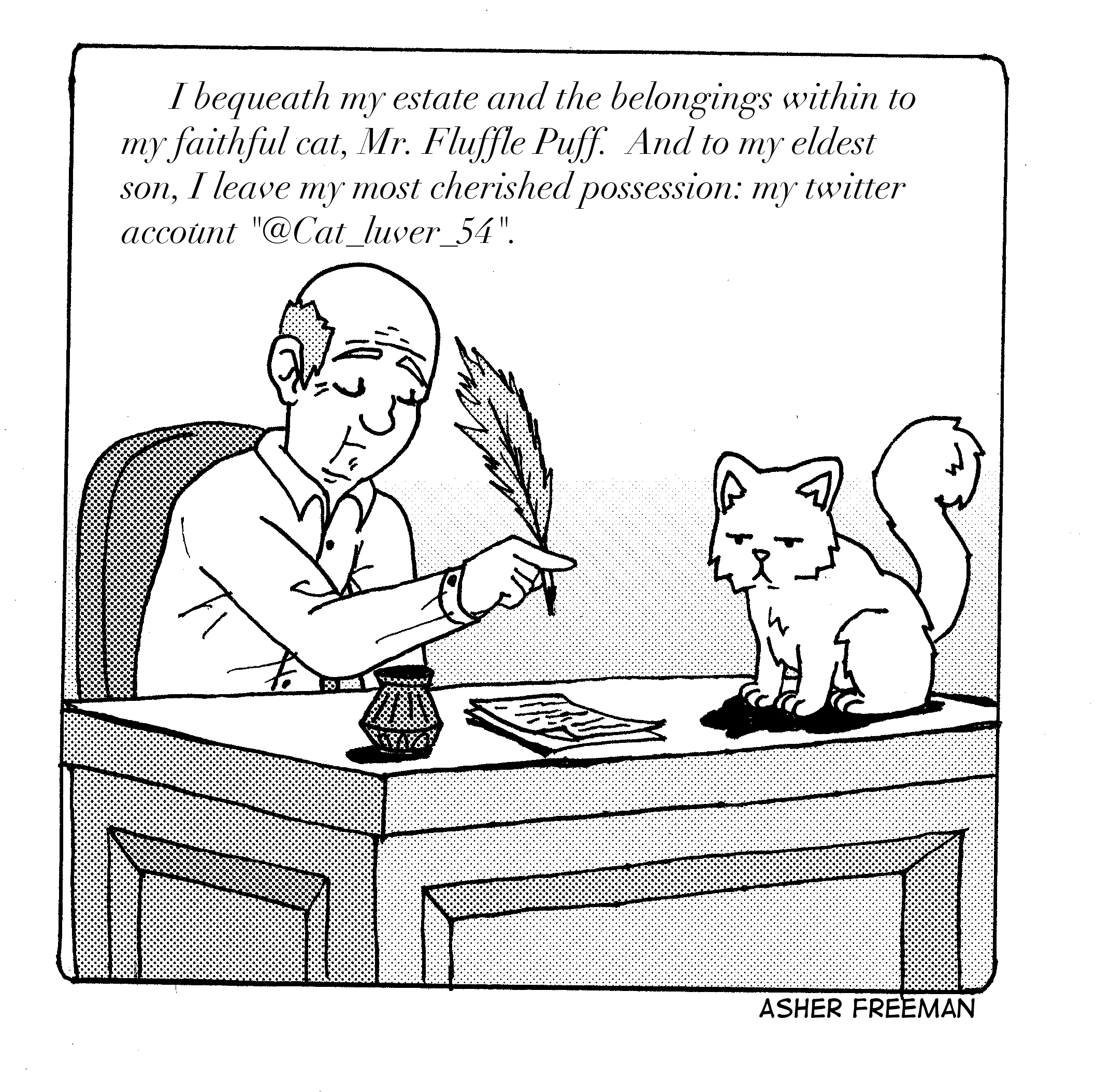

The digital revolution has created an increasingly thorny end-of-life issue: when we die, what happens to our online accounts and our Facebook pages, or to all the photos, genealogy records, recipes and other content we’ve saved in the cloud?

To deal with these complications, attorneys and other end-of-life experts now encourage clients to create a digital estate plan—a document listing all digital activities and assets, as well as login information and instructions for how to handle each account after death. That includes email, cloud storage, social media profiles, money management, health and medical portals, frequent flyer and travel memberships, web hosting or blogging information, and entertainment and shopping website accounts.

“People can’t inherit what you designate in your will unless you tell them how to get at it,” said Judith Kolberg, author of Creating Your Digital Estate Plan (2015).

Will your autopayments go on without you? Will your heirs know how to find your online accounts?

A digital estate plan doesn’t take the place of a will; rather, it should be prepared in tandem with a will and other end-of-life documents. Experts advise against including passwords or other login information in a will, as it would be inconvenient and expensive to update every time a password changes. Also, wills become public record after a person dies, so it’s possible someone could use the information to fraudulently access accounts. The digital plan serves as an easily updated addendum to help execute the deceased person’s wishes as stated in the will.

Taking this step can reduce hassle for heirs or executors, as well as prevent fraud, Kolberg said. The digital estate plan should be stored in a password-protected spreadsheet, as well as on a paper copy kept in a safe deposit box or other safe place. She also advises making appointments with yourself to update the plan regularly.

“Tie updating your digital estate plan to another activity that you do on a regular basis, such as your changing your automobile oil or paying your quarterly taxes,” Kolberg said.

Why Worry about It

“You can’t take it with you” applies to online assets just as it does to family heirlooms. Photographs, recipes, genealogy records and writings stored online over the course of a lifetime must be dealt with when someone dies: deleted, transferred to physical storage (such as a thumb drive) or maintained by someone who can continue to pay the annual or monthly storage fees.

All those pages of “Terms and Conditions” that users typically flip past when creating online accounts contain the specifics for what happens after death at websites such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, or to email. Heirs typically don’t have claim to that material.

“Those are usually restrictive about post-death access,” said Carl Levy, a trusts and estates attorney at Chiesa Shahinian & Giantomasi in New Jersey.

For example, Facebook owns all the content, including photos, that people upload to the site. While Facebook hasn’t generally deleted the pages of deceased users, there’s no guarantee that the social media network will preserve them in perpetuity. Facebook users who want their material to “live on” should download photos or other content onto a hard drive or find other ways to preserve it. A Facebook user may also name a legacy contact, a person who can either delete the deceased’s page or maintain a memorial page.

Accounts that store content—such as movies, music or TV shows on iTunes or eBooks on Kindle—usually “die” with the account holder. Heirs can’t continue to use the content. That’s because the user didn’t purchase the material itself, just a license to use it, which typically expires upon death. However, to date, these sites haven’t shut down accounts of people who die, nor taken steps to prevent family members with login information from continuing to access the content.

For cloud-based content created or owned by individuals—such as photos, recipes or genealogy records—the biggest concern becomes ensuring that the material is stored or maintained after death, if desired. If payments lapse for the host account, legally the website can delete material.

Money Matters

With the advent of online banking and investing, it’s conceivable that someone could die leaving almost no paperwork behind. Many people manage investment accounts on a paperless basis. Updates on accounts and bills may come exclusively through email. When a paperless person dies without leaving specific information on his or her online accounts, that leaves a major headache and investigative chore for heirs.

Reconstructing a dead person’s accounts “is a hassle, but it’s getting easier,” Kolberg said. Many banking and investing websites now offer options, usually under “settings,” where family members can find instructions for what to do if the owner dies.

To locate banking and investment accounts, heirs can start with the deceased’s federal income tax return. Except for newly acquired accounts, investments should be listed in Schedule B, Schedule D and/or 1099 forms. Heirs can contact the investment institutions, and after they provide a death certificate and the deceased’s social security number, the institution will generally transfer assets into an estate account. That’s a new account opened after someone has passed away, into which the executor deposits the deceased person’s money. This allows for bill and debt paying and, ultimately, distribution of funds to beneficiaries.

Once an estate has been settled, the executor should make sure that online accounts are closed.

“Anything kept up is susceptible to phishing and hacking,” Kolberg said.

Naming a Digital Executor

Some experts recommend designating a “digital executor” who can navigate and implement the digital estate plan—someone trustworthy who also knows how to handle online accounts, especially if the principal estate executor isn’t tech savvy. However, others advise against this approach.

“Having one person that handles solely the digital aspect and another handling the rest could be cumbersome,” said elder law attorney and financial advisor Patrick Simasko of Simasko Law in Michigan. “Most of the time, you would want only one executor.”

Some states don’t legally recognize digital executors; some have not yet enacted any legislation relating to digital assets. Individuals should seek an attorney’s advice on adding a digital executor.

Those sorting out a deceased person’s digital property should proceed with caution.

“While having a list of accounts, websites and login information is certainly helpful, care must be taken in accessing the account or website,” Levy said. “States are beginning to adopt statutes which govern who is allowed to access online information and under what circumstances.” (In general, an estate’s executor can access the deceased person’s online accounts, but terms and conditions vary.)

Further complicating the issue are federal statutes that protect privacy and impose penalties upon those who access online information without following proper procedures. But unless fraud or theft occurs, those statutes are rarely enforced, according to Julie C. McKain, an estate planning and probate attorney in Rockport, TX.

“… The problem is, the technology is evolving faster than the law’s ability to keep up.

–Julie C. McKain

She advises clients to tread lightly—wait until the executor is named, which typically takes 30 days after the person passes away, before accessing the deceased’s online accounts. However, if an online account must be accessed to prevent a loss to the estate, she does tell clients to take steps such as halting auto-payments.

This is one of those areas where the law and a website’s terms and conditions don’t really impact what the average American does after a loved one dies,” McKain said. “The problem is, the technology is evolving faster than the law’s ability to keep up.”

If in doubt, heirs should consult an attorney before accessing any online accounts. In addition, if an estate is involved in ongoing or threatened litigation, executors must be careful not to destroy anything that might be evidence—including digital assets.

Some online investment and banking accounts can be handled after death without logging on. Instead, a family member or executor may notify the provider about the death (with appropriate documentation), and the provider will close the account.

To navigate all of this, a growing number of services are emerging to help individuals think ahead about what they’d like to see happen in the event of their deaths and to assemble and update all relevant information into one place. Websites such as Assets in Order, Estate Map, PasswordBox’s Legacy Locker, and SecureSafe allow users to input online accounts and encrypted data and to name trusted family members or friends who may access the data. Other sites, like FinalRoadmap.com and Everplans.com, guide users in assembling login information as well as creating an online repository of health care directives, funeral wishes, plans for pets, family photos, even favorite family recipes. FinalRoadmap also allows users to craft messages that will be automatically sent to loved ones after death.

But user beware: dozens of businesses have sprouted up in the area and a shakeout is likely; some have already shut down or been absorbed by other companies. Before choosing an online repository, you should check to see what guarantees are in place should the company merge or go out of business.

Keeping Social Media Alive

Should you maintain a social media life after death? Heirs may wrestle with that question if the deceased had been an active presence on Facebook or other social media. They usually have three options for each account: delete it, leave it as is or have it turned into a memorial account.

Accounts that no longer serve a purpose, like LinkedIn and dating sites, should be deleted. Same for selling or shopping accounts such as eBay or PayPal.

Other decisions are less cut and dried. Some families opt to leave social media accounts “as is” but that option can have unforeseen consequences. Active Facebook accounts, for example, may generate unsettling alerts and notifications—such as a friend recommendation for someone who has passed away.

Also, a dead person’s online presence can create opportunities for phishing, hacking or scamming. One scenario, Kolberg said, is that a scammer might see the deceased’s alma mater on Facebook, then contact the family posing as a college representative and proposing a donation to a bogus memorial scholarship fund in the person’s name.

On the other hand, setting up a memorial social media page can serve as a way for friends and family to process grief and remember someone who has died.

Nowadays, we live on online, even after we pass away.

–Sara Ivey

“Facebook creates this visual, multimedia ecosystem,” said Molly Kalan, a Boston-based marketing executive who wrote her master’s thesis on how people grieve on social media. “It’s a dynamic archive of stories, and people can keep adding to those stories. The page can commemorate a birthday or anniversary. You can reflect on that as you go through different waves of grief. I think it’s a positive.”

More than six months after her husband’s death, Ivey continues to monitor his email account. From time to time, she receives emails with key information, such as a notice of an old 401(k) account that her husband had apparently forgotten about and that she didn’t know existed.

While she expects to shut down his email soon, Sara Ivey plans to keep her husband’s Facebook page up indefinitely.

“That’s important to me, to keep his memory alive,” she said. “It has become a forum to stay connected with family and mutual friends.”

Having gone through the process, Ivey has designated her older son as the person who will manage her online presence should something happen to her.

“Nowadays, we live on online, even after we pass away,” she said.

Freelance writer Mary Jacobs lives in Plano, TX, and covers health and fitness, spirituality, and issues relating to older adults. She writes for the Dallas Morning News, the Senior Voice, Religion News Service and other publications; her work has been honored by the Religion Communicators Council, the Associated Church Press and the American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Visit www.MaryJacobs.com for more.