Fiona, a woman in her 70s living with Alzheimer’s disease, announces to her husband, Grant, “We are at that stage.” She means the point at which she belongs in a nursing home. Her husband, like almost all family caregivers, finds it hard to take that step. But Fiona says, “You don’t have to make that decision alone, Grant, I’ve already made up my mind.” That’s a shocking statement, in part because people with dementia find making decisions difficult.

Fiona is so determined that on moving day, she precedes Grant into the building and checks herself in. Yes, she checks herself in! She walks with a perfect gait, she has no problems with language and she is beautifully put together.

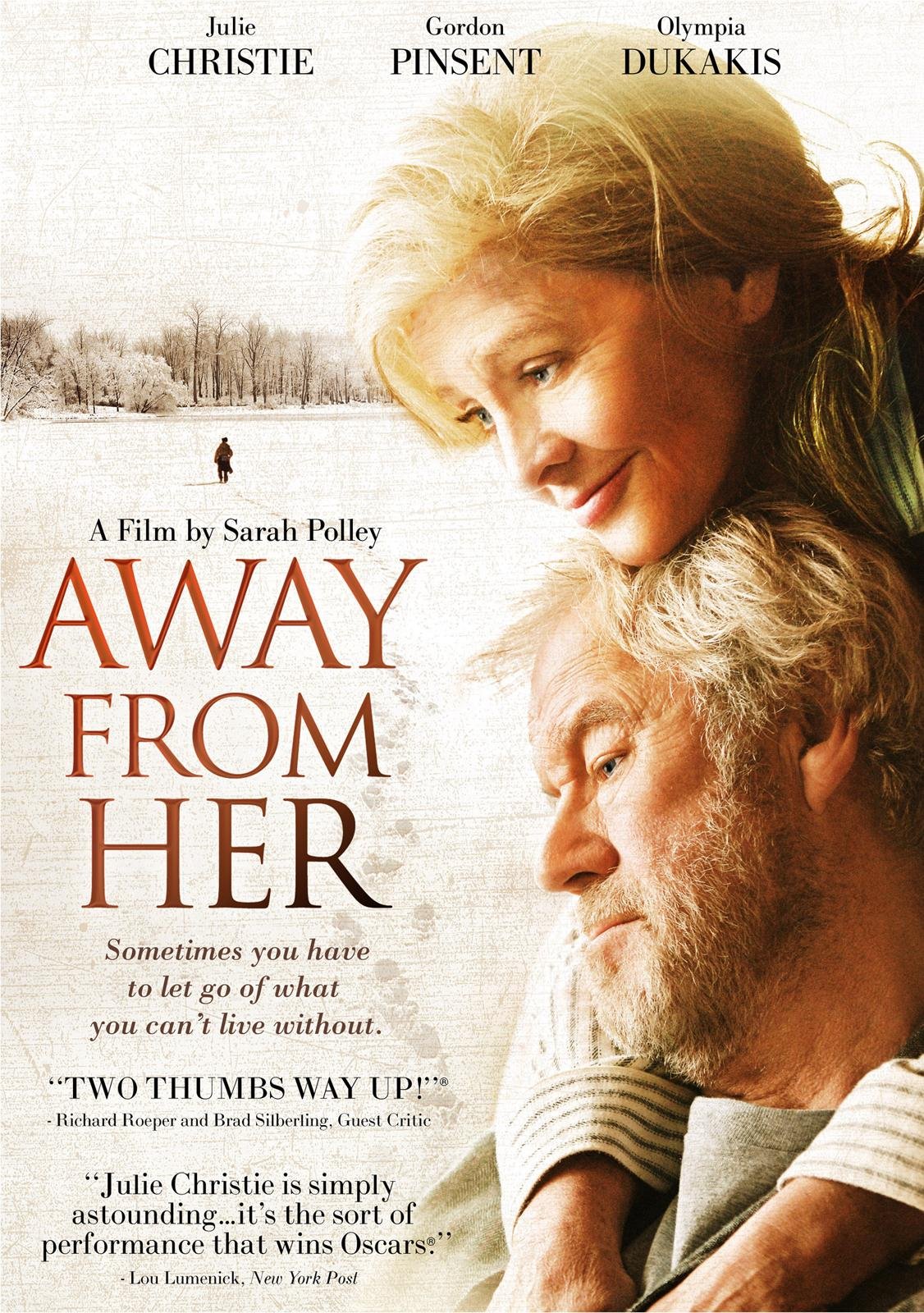

Grant and Fiona are the main characters in the movie Away from Her. It is based on a short story, “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” by Alice Munro.

Away from Her was one of the films that came up last summer when I googled “Alzheimer’s movies.” Curious to see how accurately they portrayed dementia and/or the caregiving relationship, I watched eight of them.

Four movies mostly got the disease and caregiving right—I wrote about them in my last blog, “Dementia in Films: Getting It Right.” But the four other movies are misleading in sometimes glaring ways.

A distorted picture of the nature of Alzheimer’s is a disservice to countless people with the disease, and to their caregivers who struggle daily to keep their expectations of their partners realistic. They both are hurt by illusory models of what one might expect of someone living with dementia. They—and all future givers and receivers of care—are also hurt by examples of destructive caregiving that go unacknowledged as such.

Away from Her ended up on my “got it wrong” list because it turns the caregiving relationship on its head.

In reality, the person with Alzheimer’s becomes increasingly dependent emotionally (as well as practically and physically) on the care partner. So much so that people cling and follow their partners around, unable to bear being separated from them. They fear abandonment and frequently ask for reassurance that the caregiver won’t “put me away someplace.” They do not check themselves in at a nursing home.

There is much intentional ambiguity in Away from Her regarding whether Fiona’s voluntary separation from Grant and her subsequent attachment to a male fellow resident in the nursing home are retaliation for Grant’s former infidelities. However, scheming for revenge is also beyond the ability of someone in moderate Alzheimer’s.

Based on the evidence, one could conclude that either Fiona didn’t act out of revenge (because she couldn’t), or she didn’t have dementia.

What I really think is that Alzheimer’s is a device in the story, tailored to fit the needs of the plot. Away from Her fails the accuracy test.

Two other movies on my list, The Notebook and Lovely Still, similarly use the disease simply to serve their plots.

The Notebook is based on an engaging but sentimental romance novel by Nicholas Sparks. It goes badly astray, however, in its depiction of dementia in the female lead character.

We are given a woman, living in a nursing home in the later stage of Alzheimer’s, who seems to have no symptoms except memory loss and impaired face recognition. This is patently absurd because late dementia affects multiple regions of the brain.

The woman’s brief spells of lucidity are a phenomenon that does happen in some people with dementia, but the conclusion of this movie challenges all credulity.

Lovely Still, a late-life romance, oozes sentimentality. A charming older woman comes into the life of a lonely older man. Hints that there is something more going on appear from time to time, and late in the movie when the revelation comes, it is stunning.

However, rather than justify–as it should–everything that comes before, it shows the story to be a hollow fantasy.

It presents us with the same false picture of late Alzheimer’s as did The Notebook. However, stretching credibility even further, in this case, instead of the person being in a nursing home, he is living alone in the community and remembering to show up at work every day. On the other hand, he forgets he even had a family. That’s all highly unlikely.

All stories about Alzheimer’s are, in part, stories about the disease’s impact on a relationship. The Swedish film, A Song for Martin, makes that its focus. It’s about two musicians, Barbara and Martin, in their early 60s who fall madly in love, leave their respective spouses and marry.

After an early period of delirious happiness, a cloud descends as Martin becomes forgetful and confused. He is diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. At first, Barbara tries to protect him, but as his disease worsens, she fails to adjust her expectations of him. She keeps pointing out his mistakes and tries to justify her criticism by enumerating his flaws.

All caregivers feel some anger at what fate has dealt them. Most grow beyond that. Barbara, to her own detriment and that of her husband, stays stuck.

Scene after excruciating scene had me cringing and saying aloud, “Don’t say that!”

The worst is when, after escalating friction between them, Barbara is cleaning Martin up after a bowel accident. In a voice of cold steel, she says as she helps him into the bathtub, “No need to be frightened. I’m right beside you. That’s why I gave up my job. So I can stay here and take care of you day and night. I hate doing it, but I do it because you’re a poor, helpless soul who’s dependent on me.”

Things reach a crescendo at a restaurant when Martin gets lost on the way to the bathroom. He wanders around and soon can be seen peeing in a potted plant, to the horror of nearby guests.

When Barbara sees this, she jumps up and grabs him, saying “Stop that! Get out of here! You’re behaving like a pig!”

She appears to have no understanding of what desperation a cognitively impaired person feels when he can’t find the bathroom.

Martin does what anyone—Alzheimer’s or not—would do if unexpectedly grabbed and yelled at: he punches her. She continues to yell at him and he fixes her with a hateful stare as he keeps swinging his arms. He is pinned down by others. Soon a doctor is injecting him with a tranquilizer. He is taken to a hospital for observation and will later be discharged to an institution. The doctors treat this as an inevitable end, rather than an avoidable consequence of misguided treatment by a caregiver.

Wasn’t it Barbara who initiated the violence by grabbing Martin? And yet, it is Martin who will be labeled “violent.”

In the ambulance on the way to the hospital, Martin turns to face Barbara and says, “You let me down.”

Sometimes high emotion can induce clarity in people with dementia, and this is one of those times.

In the hospital, when Barbara is about to leave him, she breaks into tears. He asks, “Why are you crying?”

She replies, “I think it’s awful that I have to have other people care for you.”

He says, “I don’t think so.”

Alzheimer’s was rendered fairly in the film. The context in this instance is a caregiver who lacks insight and never steps back for an objective view of what she is doing to the self-respect of her husband.

The movie shows us the effect of that kind of care on the person living with dementia, but it’s not at all clear that it does so intentionally. Everyone around Martin seems to regard his violent reaction at the restaurant as a sign he has gone off the deep end. And no one seems to hear the truth that Martin himself speaks on that fateful night. Barbara let him down.

Is there anything to learn from these four movies that fall short?

A Song for Martin is the only one that shows a realistic Alzheimer’s disease, but it makes it seem as though dementia destroys relationships. It doesn’t. Insensitive caregiving damages relationships and defeats the person with Alzheimer’s.

Caring for real Alzheimer’s in a loving way is possible, but you need to keep adjusting your expectations to what those who are living with dementia can realistically do, and you need to understand that they’re doing the best they can. Learn all you can to keep your expectations in line. And when tensions rise, step back and remember that a fragile ego is in your hands to carry gently or to crush.

Maggie Sullivan has come to know Alzheimer’s intimately. She was caregiver and advocate during the eight years her mother lived with the disease. For the past 30 years, she has facilitated caregiver support groups for the Alzheimer’s Association, learning from the experience of more than 300 members of those groups. The opinions she expresses here are her own. Maggie is also a writer whose essays and articles have appeared in the New York Times and elsewhere.