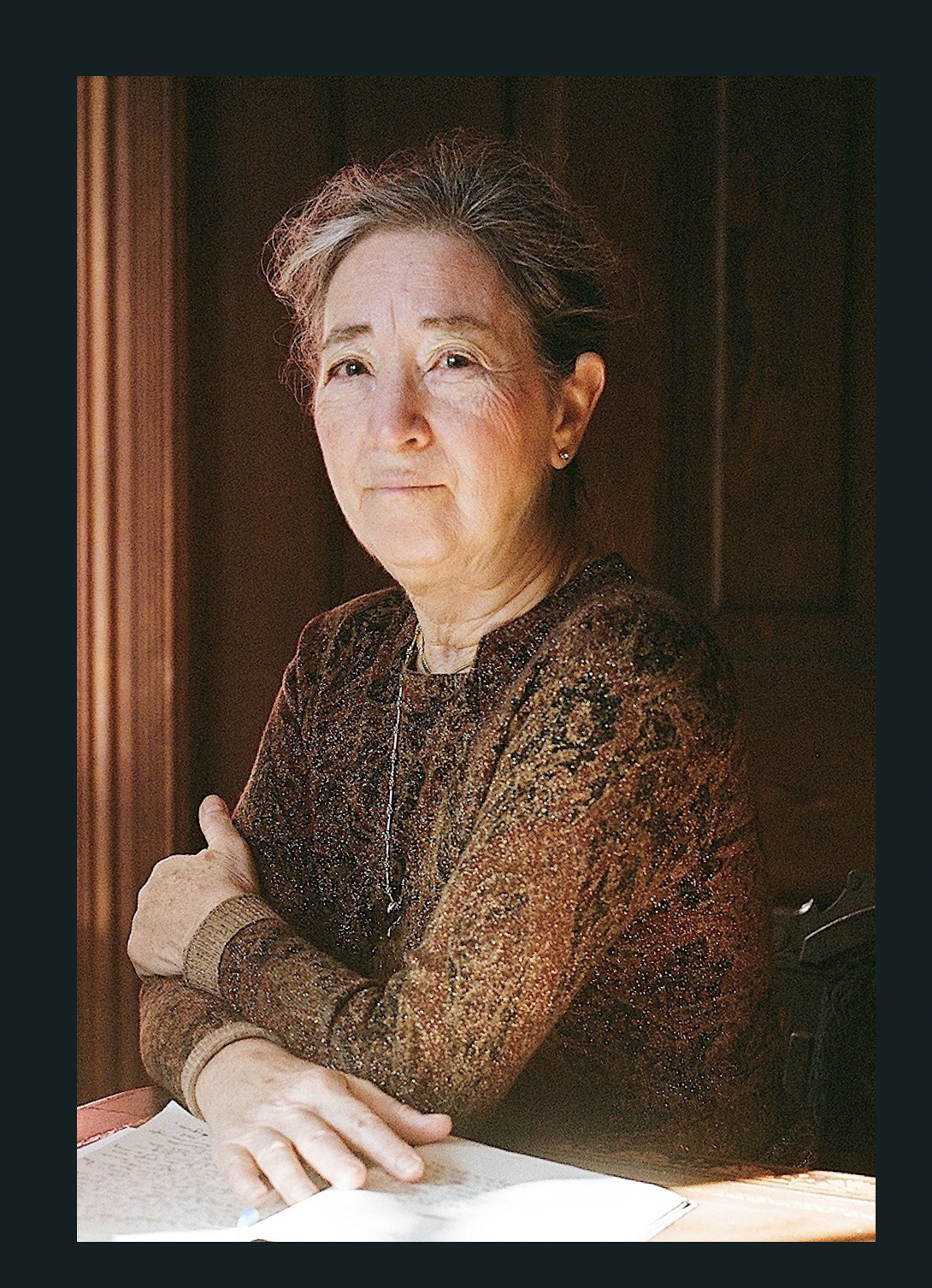

Margaret Morganroth Gullette, a resident scholar at the Brandeis Women’s Studies Research Center, is the author of Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), from which this piece is adapted and expanded.

The Internet is notorious for commenters who feel grossly entitled to dismiss vulnerable others. This past summer, Harvard University hit hard against racist and sexist speech on Facebook, rescinding admissions to some potential first-year students.

But what of ageism, which is easy to find on similar sites? Young people’s smug inflictions of pain make older people another targeted group. In various ways, they (we) are seen as too different, less than human. “Weird,” in the youth idiom.

If you google “weird old people” on the web, you can find links to scores of sites with mocking pictures and sometimes mocking captions. You can find a site called “Obnoxious Old People’s Habits, Explained.” Or google “old people having fun” or “weird old women” to see photographs aping cartoonishness. Some images make old women appear sinister, threatening—or comatose. Nursing home attendants, ignoring privacy laws, have been known to take “explicit” photos of their clients. Some posted these on Snapchat. “They just blew everything out of proportion,” whined one attendant, who spent three days in jail. “It was just a picture of her butt.”

Wikipedia has an article that explains why old people smell, which means taking for granted that they do. This reminds some of us of the Jim Crow era, when writers who explained why “Negroes” smelled were not excoriated.

“God forbid these miserable once-were-people not [sic] survive as long as possible to burden the rest of us.” This was a fantasy wish—that a large, identifiable group, “miserable once-were-people,” should die prematurely for the convenience of those who were younger. In 2011, it shocked me into discovering those I call the “elder-hostile” among the young.

This first exposure, a wake-up call, occurred when Alison Stripling and two psychology colleagues presented a poster at the Gerontological Society of America conference. The researchers called ageism on the Internet “ubiquitous.” There was more. The reports of verbal ageism on social-networking sites go back before 2011.

In 2013, this imperious declaration appeared on Facebook: anyone “over the age of 69 should immediately face a firing squad.” Of the Facebook groups that focused on older individuals, with a combined 25,000 members, one study found that 74 percent “vilified” older people, and 37 percent would like to ban them from public activities like driving or shopping. More than one of the elder-hostile wanted somebody to get a gun and kill them en masse. This data was collected by Becca Levy, a professor of psychology at the Yale School of Public Health, and her team. “These are the [social media] groups older people are likely to come across,” Levy commented.

These Facebook groups were created by younger adults whose mean age was between 20 and 29. Ten of the groups were “offensive” in terms of Facebook’s own community standards list. Since Facebook is used by 2 billion people a day, how its reviewers moderate its content matters. But Facebook did not list “age” among its protected categories. Eight of these groups remained in operation nearly a year later. On Facebook, extreme youth rules. The average age of the company’s employees is 28. They might not even notice ageism.

On unmoderated sites, anonymity encourages frightening deindividuation, a herd mindset. In a study called “Trolls just want to have fun,” Erin E. Buckels and colleagues find that men, already known to be higher than women in antisocial behavior online, admit to spending more time putting up hostile remarks. One meaning of “LULZ,” the unlikely plural of LOL, is a nasty laugh at someone else’s expense. Some trolls admit they feel “glee at [imagining] the distress of others,” if that distress is caused by their words. Their sadistic pleasure is a fantasy about possessing power over a group they project as disgusting and alien.

Numerous attacks on LULZ culture have pointed out its arrogant sexism and white-supremacist racism, but so far few media critics have attacked its barbaric ageism and ableism. Ageist humor hurts, like sexist and racist LULZ. Such verbal contempt and terrorist threats offer a troubling peephole into the biases of (some) younger adults. Mary Beard, a British historian, was the target of ugly, misogynistic ageism. Beard, as quoted in the New Yorker, believes that “comment sections expose attitudes that have long remained concealed in places like locker rooms and bars.” Ageist humor on social media is just the tip of a huge iceberg of disregard, jeering and aversion in our culture. Trollish attitudes are out in the open. They don’t need anonymity.

The New Yorker recently (September 25, 2017) published a “humor” piece called “Our Parents Are Our Future,” which ends “Hey, if nothing else, I raised two adults who grew all the way into feeble-bodied octogenarians.” Written in the voice of a ditzy daughter who is advising other millennials on how to “raise” old parents, mostly by disregarding their burdensome needs, it manages to transmit a clot of the dehumanizing clichés that age critics try to counter in their undergraduate classrooms. The advisor infantilizes old people, mocks their hearing and memory losses, whines about the incessant phone calls made by a mother with Alzheimer’s disease. LULZ.

Despite growing longevity, or perhaps because of it, it’s becoming normal to refer to old people as “burdens” and to anticipate old age as an unalleviated decline. Ageism is the prejudice that some people flaunt, and others never notice. It isn’t always as obvious as in these instances. Do we see ageism in the repeated Republican efforts to defund Medicaid or to prevent people living in nursing homes from suing when they suffer harms? To reduce Social Security’s baked-in promises? We should learn to notice, call it ageism, express our feelings of outrage and start changing our dangerous culture.

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.