2015, UK, USA, 104 min.

Bill Condon’s Mr. Holmes moves at a drip’s pace. What sounds like a condemnation is actually high praise. This beautiful drama is a profound meditation on how we live with (and evade) hard truths as we age. It has to move slowly so we can soak in every emotional turn—and savor them for later.

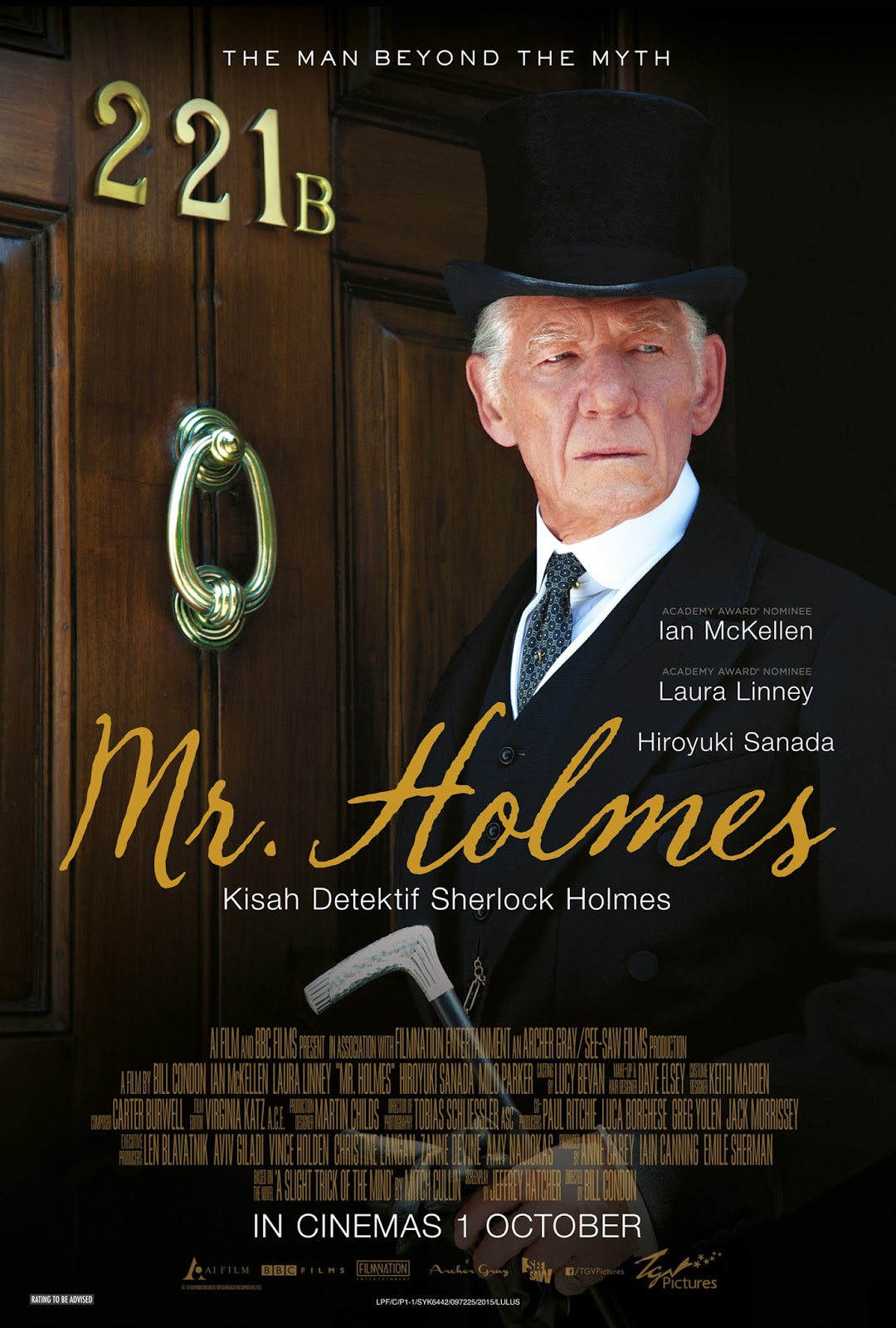

It’s 1947 and Sherlock Holmes (Ian McKellen) is nearing the end of his life in a seaside cottage, where he’s cared for by his housekeeper, Mrs. Munro (Laura Linney), and her sly, smart son, Roger (Milo Parker), who admires the legendary detective. On the surface, it’s a peaceful existence: mail is delivered by bike; the doctor makes house calls.

But Holmes is suffering—and in exile. Adding to the horror is that his memory, his biggest asset, is eroding. He knows his self-inflicted punishment has something to do with his last case. He remembers snippets that refuse to coalesce. Every attempt to save his mind leads nowhere. This is a difficult situation for anyone, but especially for Holmes: his life and his public persona are based on logic and certainty. Those compose his soul, which has been caged for 35 years. He can’t pull any miracles from his sleeve: the names of acquaintances he can’t forget—written in pencil in a wobbly, faded hand—reside on his shirt cuffs. Roger, eager for a real, live father figure and for a true Sherlock Holmes story, is undeterred. He urges Holmes to write what he remembers.

Condon (Gods and Monsters, Kinsey) doesn’t tip the story toward one direction, like the young learning from the old. (In fact, that backfires when Roger employs Holmes’ disdainful attitude on his poor mother.) This is about a man at the twilight of his life forced to face himself, devoid of friends and family, and far removed from the stares of tourists wondering where his pipe and hat are.

Mr. Holmes isn’t about Sherlock Holmes. (Heaven knows there have been enough movies about him.) It’s about us, and who we become. In trying to align ourselves on the right side of the past, we are all working on our own mysteries. Why am I no longer in contact with this person? When did I stop caring about this particular thing? Is it more important to be happy or to be right? Holmes is forced to solve who he really is, not the public’s perception.

This is not an acting showcase, though McKellen and Linney, as expected, are terrific. Condon, to his credit, refuses to let the pair do all the heavy lifting. He allows scenes to breathe. We can practically hear Munro’s weariness over a thinly veiled barb from Holmes. We can see the pockmarks and lines on Holmes’ face and see that this is a man with the burden of an unsolvable problem who doesn’t have enough time to solve it. The use of natural light in Holmes’ house makes it look as solemnly comfortable as a church during a morning funeral service. Mr. Holmes carries the weight of the everyday with it, and that makes Holmes’s plight—and his effort to rid his psyche of that unknown torment—so recognizable. And Condon’s stiff refusal to rush the proceedings heightens that very real tension.

It’s fitting that Holmes’ story comes together when he no longer treats his employee and her son as suspects for household infractions. His life opens up when he lets people into it. Mr. Holmes is wonderful not only because Condon, writer Jeffrey Hatcher and the cast portray the later years with grace and insight, but because the film does so with a character whose cold brilliance normally prohibits that kind of treatment.