Since the publication of This Chair Rocks: A Manifesto Against Ageism (2016), I’ve been asked a lot of questions. Are you curious about why I find aging so damn interesting? Why I dislike the term “successful aging” so heartily? Answers to these and a few other good questions are below in part one of a two-part post.

You want to reframe the way American culture sees age and aging. What got you started on this path?

About eight years ago I began interviewing people over 80 for a project called “So when are you going to retire?” and reading about longevity. It didn’t take long to realize that almost everything I thought I knew about aging was wrong. I had no idea that people are happiest at the beginnings and the ends of their lives, for example. That the vast majority of Americans over 65 live independently. That the older people get, the less afraid they are of dying.

Why don’t more people know this stuff? Because we live in a culture that drowns out all but the negative about growing old or even just aging past youth. Why is that? Because social and economic forces frame aging as a problem, so they can sell us remedies to “fix” or “stop” or “cure” it. Aging is a natural, lifelong, profoundly enriching process—experience tells us so. Aging means living, which is why it’s so damn interesting. And to paraphrase British journalist Anne Karpf, it makes no more sense to be anti-aging than anti-breathing.

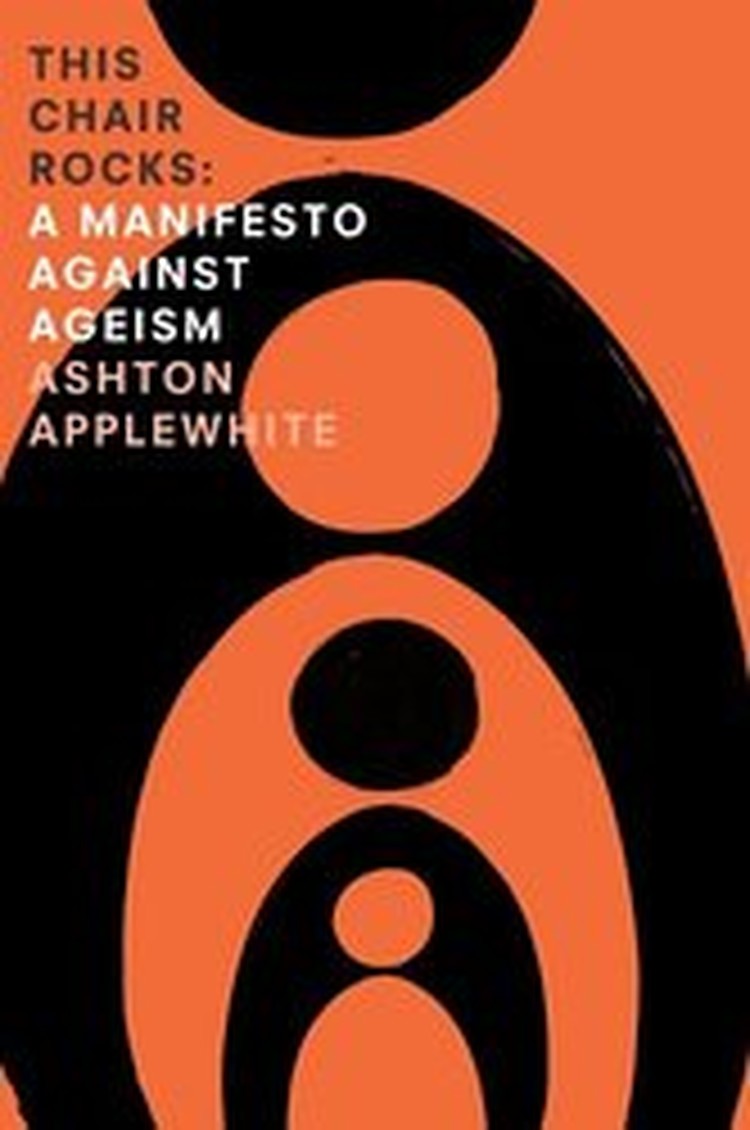

How did you arrive at the arresting cover design?

We gave designer and friend Rebeca Mendez a tough commission: come up with a cover that feels warm and human but also sharply political. And will jump out at readers from a crowded bookstore window. She was scratching her head until my partner suggested that the epigraph of the book might serve as inspiration. It’s a quote by the wonderful writer Anne Lamott: “We contain all the ages we have ever been.” Rebeca’s painting beautifully captures that idea.

An ageist society aspires to “agelessness,” an artificial and unattainable goal that strips us of our years. I love the way the cover represents the opposite, which I call “agefulness”—a rich accretion of all the things we’ve done and been, stored within our bones and brains, that makes us who we are.

If you could banish one stereotype about aging, what would it be?

The notion that older people are alike! It’s why people think everyone in a retirement home is the same age—“old”—even though residents can span four decades. (Can you imagine thinking that way about a group of 20- to 60-year-olds?) It’s why the last box on those marketing checklists—you know, 18-26, 27-39, etc.—ends at 65+, as though everyone over 65 buys the same stuff and does the same things.

Stereotyping—the assumption that all members of a group are the same—underlies all the “isms” (like racism and sexism). It’s always a mistake, but especially when it comes to age, because as the years pass, of course, we grow more different from one another. It’s why geriatricians say, “If you’ve seen one 80-year-old, you’ve seen one 80-year-old.” We all age at different rates—mentally, physically and socially—which is why there’s no such thing as “acting your age.” Chronological age tells you almost nothing about an individual—not what they’re listening to or who they’re voting for or where they’re headed—and the older the person, the less reliable an indicator it becomes.

You make a case for an anti-ageism campaign as a public health initiative. Tell us about that.

A growing body of evidence shows that attitudes towards aging have an actual, measurable, physical effect on how we age. There’s no inherent reason for the effect to be negative. But an ageist culture tells us that wrinkles are ugly. Old people are incompetent. It’s sad to be old. When we assimilate these stereotypes, they become part of our identity, and this influences how our brains and bodies function.

In one experiment, social scientists primed a group of college students with negative age stereotypes—words like “forgetful,” “Florida,” and “bingo”—that they flashed on a screen too briefly for the subjects to become aware of them. The students then walked to the elevator measurably more slowly than a control group! Imagine the effect on older people, for whom the terms are more relevant and thus more likely to become self-fulfilling prophecies.

People with more positive feelings about aging behave differently from those convinced that growing old means becoming irrelevant or pathetic. They do better on memory tests and have better handwriting. They can walk faster and are more likely to recover fully from severe disability. And they actually live longer—an average of seven and a half years. Everyone agrees that health has the biggest effect on how we age—and how much it costs. So think what a national anti-ageism campaign would do to extend not just the lifespan but the “healthspan” of all Americans.

Why do so many of us have such a hard time actually admitting our age…saying it out loud?

You’d have to live in a cave to miss the messages all around us that old = bad, and that aging is to be feared and avoided by any means necessary. No wonder so many of us are reluctant to part with the equivalent of a cultural “sell-by” date! It’s an understandable strategy. Attempting to “pass” for younger, the way some people of color have passed for white and some gay people for straight, is a way to avoid being discriminated against. But “passing” takes a psychological toll because it’s rooted in denial and distaste, even disgust. We’re reluctant to divulge our age because we’ve internalized the profoundly ageist notion that our older self is inferior to our younger one.

Do you honestly think that the person you are now has less to offer than the 20- or 30-something you? That you’re less interesting now? Less valuable? How about less attractive? If that gets a nod, consider the industries that make billions by commodifying our dissatisfaction with our bodies—especially women’s. Who gets to decide that wrinkles are ugly? It’s time to look more generously at ourselves, the way the body-acceptance movement urges, and to stop colluding in devaluing ourselves as older women.

When we claim our age, the number loses its power over us. It’s a little like a spell breaking. We can’t stop aging, even if we wanted to, but we can change the way we feel about it—the first step in any revolution. Then we can start to see where those ageist messages come from—and work together to challenge the structures that benefit from them.

Why do you dislike the term “successful aging”?

Terms like “successful aging” and “productive aging” and “active aging” are popular and provide an upbeat counterpoint to the standard narrative of aging-as-decline. They’re seductive, because we really, really want to think we can keep doing the things we love for as long as we live. We often can—versions of them, that is—especially if we have access to health care, and exercise and eat well. But the goalposts shift. In addition to taking care of ourselves, we’d do well to decouple self-worth from long-standing measures of earning power or physical prowess. Much is not under our control.

It’s important to keep in mind that many of the resources that help us “age well” are predominantly available to the lucky and reasonably well off. Sanitized or romanticized exemplars of “successful aging”—those silver-maned couples waltzing on the foredeck of a cruise ship—set an unreasonable standard and suggest that less “successful” agers are responsible for their circumstances.

Everyone can make sensible choices, but barriers like heavy caregiving responsibilities, inadequate health care and neighborhoods with few resources make it more difficult. Blaming the poor for “bad choices” makes aging another arena in which we succeed or fail based on terms that are far from neutral. There’s a lot of harsh judgment of olders who aren’t physically mobile or conventionally, economically productive, and that’s not OK. All aging is successful—not just the sporty version—otherwise you’re dead.