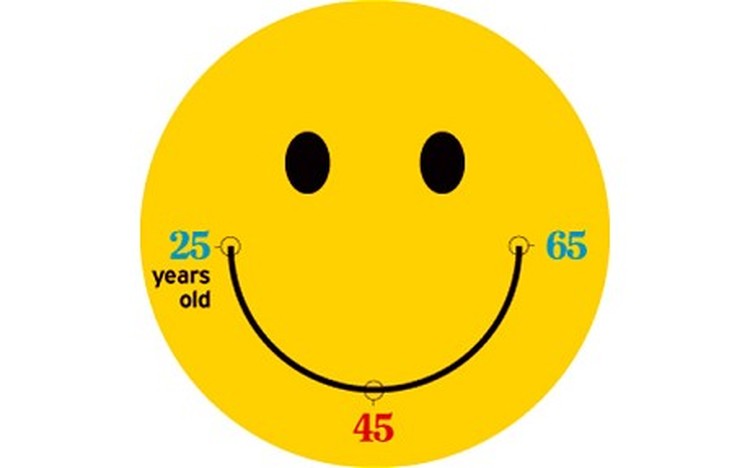

An Atlantic magazine cover story last October described living past 75 as pretty darn inadvisable. Then, in quite the about-face, the December cover story championed the Happiness U-Curve and the growing body of research showing that we reliably grow happier, almost regardless of circumstances, after our 40s.

As writer Jonathan Rauch explains in the article, this curve emerges only after researchers have filtered out significant variables, like income and marital and employment status, to reveal the effect of age alone. People don’t reach 80 without facing adversity and loss, often crushing. They have more health problems too. In other words, this increased sense of well-being is not predominantly conferred by things that happen in life. It’s not reserved for mystics or billionaires. It is deeply human and rooted in biology.

The big take-away for Rauch is the scientific fact that it’s hard to be happy when you’re middle-aged. Titled “The Real Roots of Midlife Crisis,” the article is sprinkled with anecdotes about acquaintances whose trajectories mirrored Rauch’s own. During their 40s, despite having achieved all kinds of material and professional successes, they were bushwhacked by upheavals and feelings of disappointment and discontent. Almost as bewilderingly, and also independent of circumstance, simply entering their 50s conveyed increased feelings of calm and gratitude.

Perhaps the shift towards conscious contentment is based in endocrine changes or brain chemistry. But German neuroscientists have found that healthy older people are less prone than younger ones to unhappiness about things they can’t change. Rauch describes becoming more accepting of his limitations and revising his expectations accordingly—and thus his measures of success and failure. He labels this an “expectations gap” and quotes Princeton economist Hannes Schwandt on the finding that the gap narrows with age. “[It] supports the hypothesis,” Schwandt writes, “that the age U-shape in life satisfaction is driven by unmet aspirations that are painfully felt during midlife but beneficially abandoned and felt with less regret during old age.”

Drawing on emerging cognitive science, Rauch calls this wisdom—and fervently wishes he’d found out about it in time to help him through his midlife doldrums. “What I wish I had known in my 40s (or, even better, in my late 30s) is that happiness may be affected by age, and the hard part in middle age, whether you call it a midlife crisis or something else, is for many people a transition to something much better—something, there is reason to hope, like wisdom.”

I didn’t hear about the U-curve until my mid-50s, at which point I figured researchers had cornered two octogenarians, offered them fresh-baked cookies, then asked how they were feeling. Skepticism remains widespread even as corroborating evidence mounts. A 2011 study, conducted by Laura Carstensen and colleagues at the Stanford Longevity Center, found that “the peak of emotional life may not occur until well into the seventh decade”—and also that this finding is “often met with disbelief in both the general population and the research community.”

I’d recast the big story from one about dissatisfaction in midlife to one about happiness towards the end of life. That’s the message that American culture drowns out most loudly, although ageism shadows the whole life course. Messages about being “over the hill” at 40 are everywhere you look: greeting cards, advertisements, sitcoms. Internalized and unexamined, the notion that it’s all downhill after 40 makes it all the harder to weather that midlife trough. How much better, indeed, to challenge that absurd notion while we’re still young and to be sustained from then on by the knowledge that with age comes happiness.