Not just in childhood, but deep into my middle years, my mother and I shopped together. I got most of my clothes on those expeditions, and she paid for a great many of them. It didn’t occur to me that any of this was unusual until a former roommate of mine, now with a daughter in her 20s, said that she had long admired my mother’s example and was “still” buying clothes for her delighted progeny.

Maybe this wouldn’t have worked if my mother hadn’t begun by being, on occasion, surprisingly indulgent of my childish fashion whims. At 8, I wheedled a gold lamé, two-piece bathing suit out of her to wear to the beach at Rockaway. My cousin did the same with her mother. Gold lamé! Judith and I flaunted our juvenile glitter together, jumping waves. When I was 10, my mother let me wear to school a gypsy-striped, swing skirt boasting more colors than Joseph’s cloak in the Bible.

Her own look was tailored. She wore colorful Bonnie Cashins and Claire McCardells in the postwar ’40s and ’50s, when these American designers were putting working women in functional, easy-to-wear, easy-to-keep–clean separates. My mother started teaching when I was about 10, to supplement my father’s modest income. She taught first grade for the next 25 years and appeared at family parties in separates that met couture standards. She read Vogue and bought inexpensively at a discount store in Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn that was soon to become the famous Loehmann’s.

Except when wearing the gypsy skirt, at school I daily conveyed a model, good-girl look. My mother insisted on perfect neatness. She herself buttoned my sleeves and turned up the sweater cuffs evenly on both wrists. She checked for hanging threads and hems. The school forbade pants for girls except on snow days. The one time I wore mine—a tailored, wool plaid paired with a Peter Pan shirt and a cardigan—a teacher praised me for looking “like a little lady despite the trousers.”

For college, my mother, in higher gear, authorized a small, choice wardrobe from our little disposable income. I was a scholarship student. I think her idea was that I could nevertheless pass as truly middle class if I had a few “good” pieces I could mix and match. A bride of Higher Education, I had a modest trousseau. A gray, glen plaid, Hardy Amies, pleated skirt to wear with turtlenecks. (Hardy Amies dressed Queen Elizabeth.) Of course, a little black dress for mixers, a severe crepe beauty with 50 tiny buttons. I wish I had saved those two garments. I do wear another of those freshman-year pieces now, a sleeveless, wool coatdress.

My mother imprinted me with her classic, good taste, but for decades it would have been hard to know what my taste was because I rarely bought myself anything without her. I don’t like shopping, and Boston for a long time had no Loehmann’s. Twice a year we shopped together in Florida or Massachusetts.

This was educational and made shopping less unpleasant. My mother had an uncanny talent for finding what would fit me. She brought clothes to me and gave me her opinion. In my mind I criticized her for spending so much on fashion, but I envied her eye. She had greater gifts than most fashionistas. She recognized a designer by style before she saw the label. Her color sense was so accurate, she could remember that the blouse I needed was cranberry, not magenta or burgundy or prune. She would find the exact shade of cranberry. After hours of sorting and carrying and trying on, I would be exhausted but she would be fresh as a daisy and exhilarated at our finds.

Even after I graduated and married, lived in Rome, came back to graduate school, then moved to Newton (MA), we corresponded about my “needs” and discussed them over the phone, and she shipped finds to me. Only rarely did I send a package back. Her care packages arrived even after I started working in Harvard administration. I had beautiful clothes. I always offered to pay for them, and sometimes she let me. But her idea was that mothers gave and daughters accepted. Once I got over the weirdness of having my mother buy my clothes, the whole system suited me fine. She shopped for my husband too. She shopped for my father and for my son: classic jackets, cashmere sweaters. All on her unionized teacher’s salary. She had a grand time.

For decades I looked like the good girl grown up—a professional woman in dark menswear. Impeccable, no loose threads. During that time the only important things I bought for myself were for dress-up. Frilly, feminine glitz—an ex-New Yorker’s choices for a downtown life. Thirty in 1970, I wore hot pants. I liked sequins, lace, satin, cut velvet, slouchy trousers, off-theshoulder blouses, black. My brand of feminism did not tame this “harem” side of my appearance. Dressing like a professional during the day drove the creativity, or personal taste, nightward. I was overdressed sometimes and didn’t care. It was the side of me that had danced wild at the Palace bar in Boston when I was a Radcliffe freshmanand my longhair fell out of its hairpins, and I didn’t care.

My professional look—darkly sober, restrained good taste (black/gray/charcoal/brown/maroon)—continued even after I left Harvard and became a writer. Working mostly at home, I had less need for professional clothes but I continued to wear them. I was wearing them out, all those well-made garments in sturdy fabrics. But it was also as if my mother, from Florida, still kept a gentle, loving eye on my wardrobe, making sure I was dressed appropriately. By this time I no longer needed to impress people as middle class, but I no doubt did. Was all this habit, or laziness, or loving admiration for her?

And then some things imperceptibly changed. For the first time in my life, I started to look closely at the way other women dressed. I noticed those in particular who were not dressed “appropriately.” One friend wore the odd cuts from the chic Japanese firm, Comme des Garçons. Artists I knew each had their own style: one wore primary colors; another, a man’s dress shirt over jeans.

My later-life appearance developed little by little, not consciously. By chance, by finding without seeking. Eventually I realized I had been buying daytime garments that were not dark, and not tailored, and not classic, and not at all professional. Some were brightly patterned, hand-knit wool sweaters made by indigenous Latinas. Some were merely colorful—tops in mauve, kelly green, orange. I no longer dressed like the president of a small, liberal arts college, which had once been the height of my ambition. Even to guest-lecture, I wore nontraditional outfits. I told my mother I didn’t need more clothes. (That was certainly true.) In my 60s I began to spend more time thinking about what I would wear the next morning, putting colors and textures and jewelry together with pleasure as if I were my own personal shopper or a painter. My new way was not about representing class or sexiness, it was esthetic.

My mother in her 90s shopped infrequently and from catalogs. “Shop in your own closet” became her motto. When we met, she never disapproved of anything I wore. She had long before become quite mellow about mere taste. We continued having animated conversations about Vogue, the loss of craft traditions, the sleaziness of fabrics. When she was losing her sight, I always told her how good she looked, how perfectly her clothes fit. She died in 2010, generous and loving to the end. For her cremation, I had her dressed in silk pants and a gorgeous, iridescent purple, silk blouse with amethyst glass buttons.

This is a story that covers my whole life to date. I call it an age autobiography. You can tell almost any aspect of your life this way, in fragments, over time, by figuring out what age or aging has to do with change. History sneaks into it a bit. You explain as much as you can—still there is always some mystery about changing.

But this is not a dramatic story about breaking away from my mother’s style at long last. A woman might write it that way when she was younger, when any difference from one’s mother seems like a challenge to her authority. My mother was an inveterate once-a-week shopper, and I preferred being a twice-a-year shopper. That difference didn’t bother us. What we had in common was a lifelong mutual interest. I couldn’t acquire her erudition about designers and fabric, but over time she gave me not only the garments, and for many years, a look, but something far more precious: lifelong companionship.

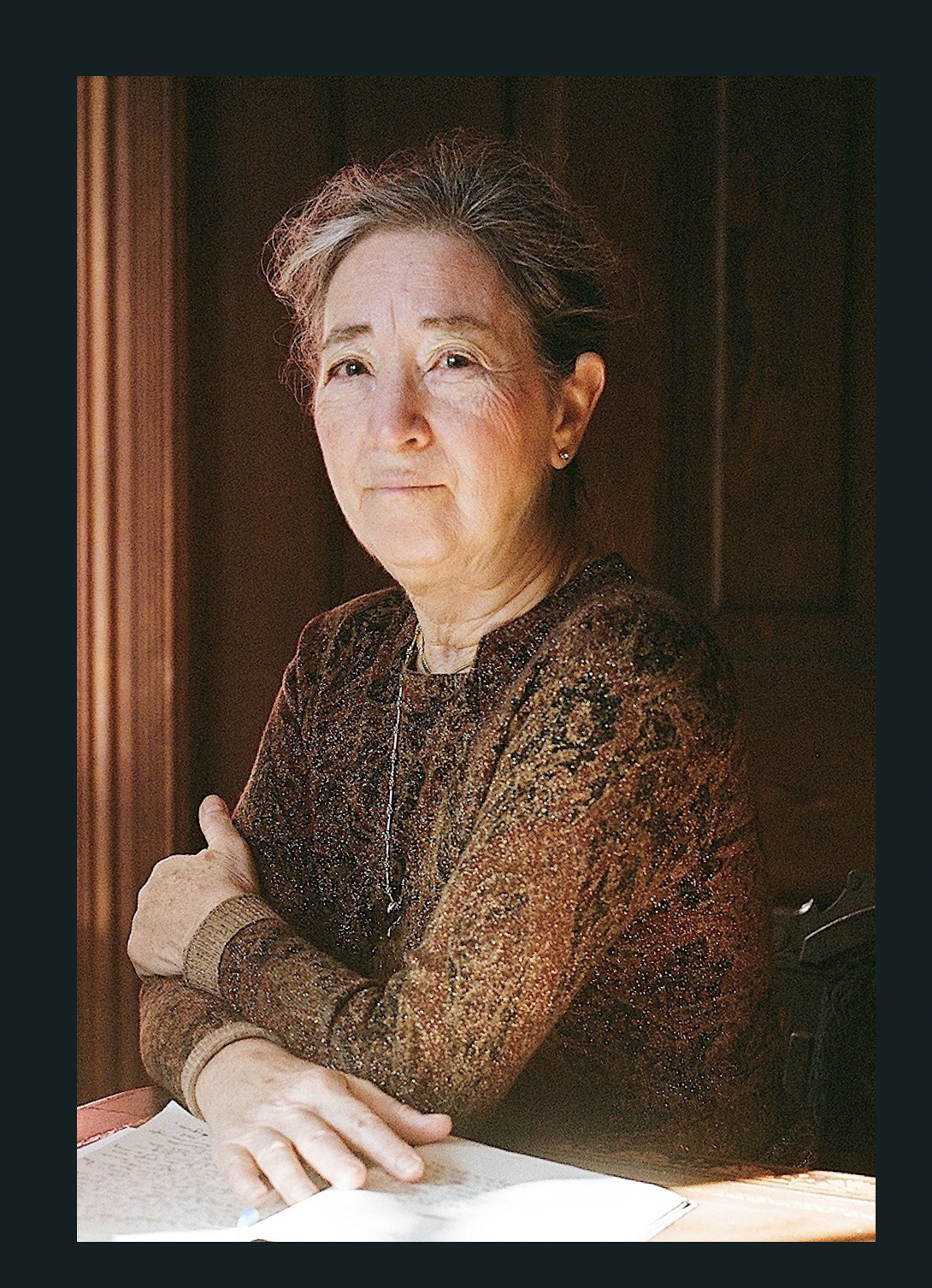

© 2014 Margaret Morganroth Gullette

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.