When I was young, everyone I knew felt some dissatisfaction when trying on clothes. Some of us found it excruciating. I used to say, “The scream came from the dressing room.”

Point of purchase was supposed to be a romantic story of love at first sight for the garment that would transform you into everything you weren’t. Think Cher in Moonstruck, a dowdy young widow turned into a glamorous mate by a new dress and hairdo, or hundreds of other films and novels also pivoting on a makeover. In truth, the point of purchase was often a point of misery. Just another bad date with a designer label. Except that it was your own body or face that wasn’t right; the garment itself was flawless.

Like getting dressed, shopping may become a better experience through aging. A lot of older women have learned to be less critical of their bodies than they were when young, and more adept at dressing the body they have rather than the ideal one they once desired. When your body looks better in your eyes, even shopping (that miserable, self-hating experience) becomes more fun.

Money was also a part of the misery in the dressing room. If perfect clothes were too expensive and you could buy only one good thing from time to time, that upped the ante. Regretfully, and sometimes bitterly, I put back on the rack many things I couldn’t afford. Now a riveting appearance is often less about money.

For many women, including feminists, not spending too much money matters as much as dressing well. And just as a house can be distinctive without being a mansion, you can be fashionable without being rich. A woman with a personal shopper and a huge budget is not necessarily better dressed than others. Some noticeable older women have no money to spare for clothes but you see them on the bus with a proud carriage and a gorgeous turban.

The other extreme—fashion as it used to be—is illustrated in Scatter My Ashes at Bergdorf’s, a documentary about the high-end Manhattan department store. Reviewing the film, Linda Barnard complains in her blog that it features “dozens of talking heads . . . blabbing about statement dressing, $10,000 jackets and shoes that cost more than six months’ rent (‘we can’t keep them in stock!’) amid lectures on how to dress.”

In an era of jeans made with exploited labor, $30,000 handbags and items that may look good for only three washings, shopping is tricky. It can be like hunting for an under-appreciated treasure in a flea market. You have to have an eye like a connoisseur—able to discern not just quality (durability, texture), but also appropriateness for your particular body (cut, color, solids or patterns, draping).

When you want to achieve visibility and satisfaction, it helps to have some disposable income, but you don’t necessarily have to spend big on current fashion. I discovered basics at a chain selling used clothes that arrive in bales. There the quirky prints I love are massed together, and nothing costs more than $7.99. Many women shop vintage or drop in at the Salvation Army.

When I was in London talking at a conference on fashion and aging in October, four women appeared on a panel wearing amazing outfits, each one quite different from another. They were the Fabulous Fashionistas, stars of a British TV documentary of that name that became an Internet hit, scoring a million viewers in short order. The Fashionistas’ average age was 74, and one is a model at 85. When the moderator in London asked about their style choices, three said their clothes came mainly from “charity shops.” The fourth said she made her own. One said she had been a bohemian and had always worn inexpensive items. The model, Daphne Selfe, wore a black-and-white striped blanket that she had cut at the neck and sewn into a poncho.

My mother, who loved to shop for designer clothes, also used to say—thriftily—“Shop in your own closet.” I do. I still possess a blue-green, sleeveless, plaid coat that she gave me when I went off to college. Taupe, a good color for me, has been unfashionable for years. So I take good care of a taupe-and-black wool cardigan from the 70s, a bold Rodier geometric print in wool.

A good friend of mine shops in her mother’s closet. When her mother died, she inherited well-made separates she loves. She couldn’t bear to give them all away. The ones she kept boast serious tailoring, linings, darts, box pleats, or hand-finished seams—all the elegances of craft that have almost disappeared from contemporary, ready-made clothes. I know four or five women my age, orphaned in later life, who wear hand-me-downs that bring them closer to their late mothers.

Most people buy new, and thus shove their psyches again into the usual fashion cycle. Point of purchase is only the beginning. After you find something you love enough to lay down hard-earned cash, you wear it and live some valuable life in it. It is you somehow: it takes on meaning from these associations. And then the garment ages, and in the prescribed way that all of us grew up in, it is time to get rid of it. It may be in perfectly good condition but it “gets old”—not worn, but old, meaning passé. Consumption needs that sad, bad ending—disposal. Business requires the discard. The fashion industry depends on it. Capitalism could not survive without it.

But you are the one who performs the rejection. And each time you go through the entire life course of a fashion, you learn a terrible narrative that mimics our ageist American life course. Bright infatuation at the moment of the first purchase (youth), accretion of meaning (midlife), waste and discard at the end. You are allowed a slight moment of sadness if you toss the garment in the trash.

You need not be aware of this subterranean, psychic journey for it to be teaching you that decline is the normal, expectable pattern. In fact, the lesson is more powerful because you are not conscious of it.

Through the practice itself, you buy into that harsh, inevitable cycle over and over again. You learn a painful decline story about aging. You practice the familiar gesture of careless disposal that will at the end discard you, with apparent inevitability, merely for getting old—your familiar and still useful body, your precious selfhood.

Saving clothes, buying cheaply, recycling other people’s castoffs, pulling together vintage pieces with a new item—these are not only style choices or economic decisions. They are, far more importantly, also ways to wriggle out of the vicious cycle. Is it just a coincidence that the women I know who do this are also antiageists? They are fighting not just one stereotype—that older women are “old bags” or “old hags”—but ageism in many other sinister varieties, also disguised (like new clothes enticing you to step into the cycle again) with fancy labels.

Antiageists are not buying creams or potions that are falsely labelled “antiaging” and that promise to unwrinkle your skin. (There is no way to prevent aging, or the appearance of aging, except by dying young.) Some people still confuse these two words that sound a little alike—but they are worlds apart in mental health terms and practices. Antiageists are not participating in the cult of youth: they don’t think beauty has an age or a short shelf life.

Antiageism has a vast agenda. Liberation comes in many pleasant and unexpected forms. Loyally holding onto old things, and looking good while doing so, is one of the liberating practices anyone can try on.

Margaret Gullette expands on the theory behind this blog in a chapter called “The Other End of the Fashion Cycle” in her prize-winning book Declining to Decline: Cultural Combat and the Politics of the Midlife.

© 2014 Margaret Morganroth Gullette

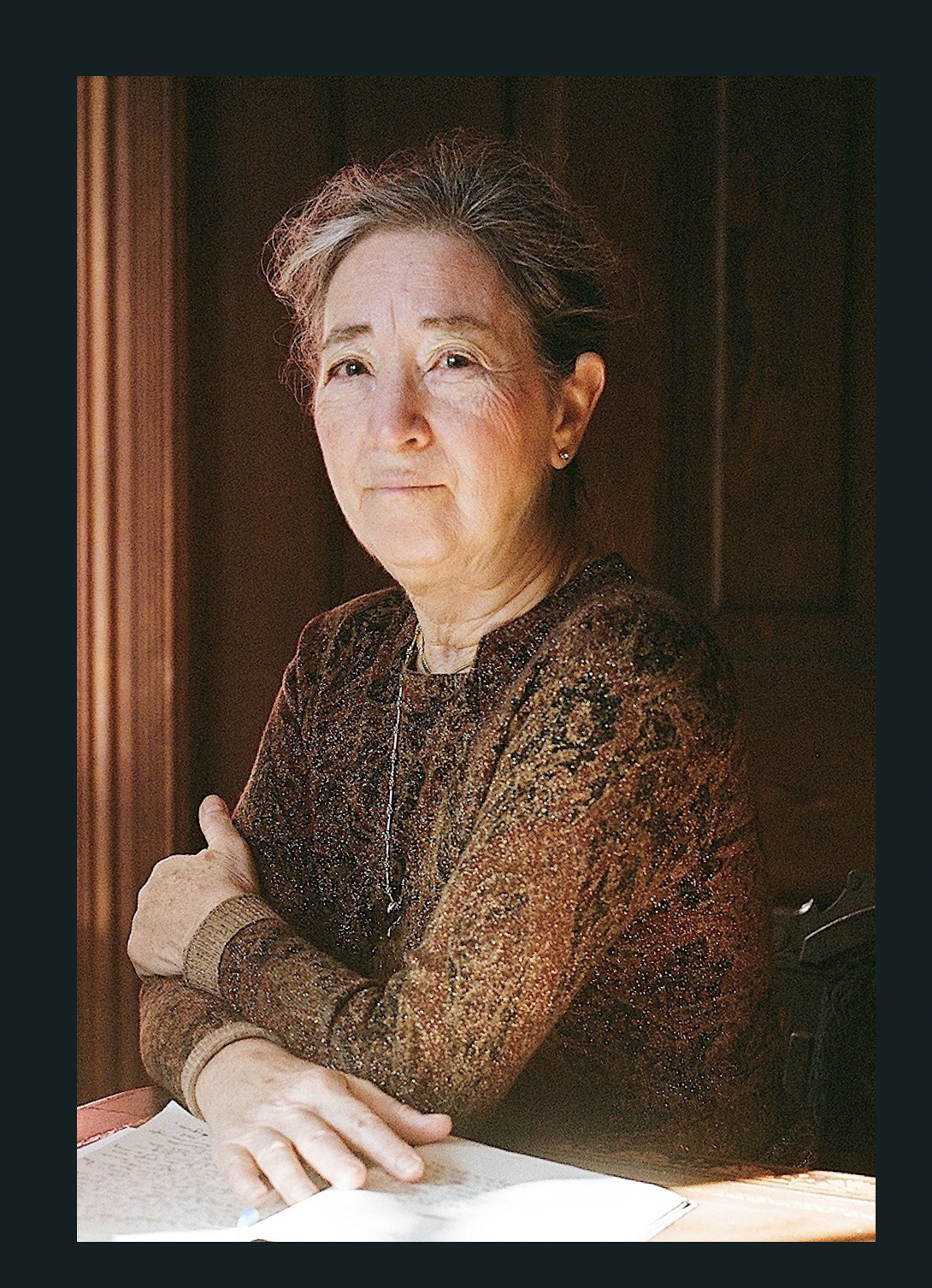

Margaret Morganroth Gullette is the author, most recently, of American Eldercide: How it Happened, How to Prevent It (2024), which has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Her earlier book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People (2017), won both the MLA Prize for Independent Scholars and the APA’s Florence Denmark Award for Contributions to Women and Aging. Gullette’s previous books—Agewise (2011) and Declining to Decline (1997)—also won awards. Her essays are often cited as “notable” in Best American Essays. She is a Resident Scholar at the Women’s Studies Research Center, Brandeis University.